Unfortunately, Paxos is quite difficult to understand, in spite of numerous attempts to make it more approachable. — Diego Ongaro and John Ousterhout, In Search of an Understandable Consensus Algorithm.

In fact, [Paxos] is among the simplest and most obvious of distributed algorithms. — Leslie Lamport, Paxos Made Simple.

I was interested in exploring FizzBee more, specifically to play around with its functionality for modeling distributed systems. In my previous post about FizzBee, I modeled a multithreaded system where coordination happened via shared variables. But FizzBee has explicit support for modeling message-passing in distributed systems, and I wanted to give that a go.

I also wanted to use this as an opportunity to learn more about a distributed algorithm that I had never modeled before, so I decided to use it to model Leslie Lamport’s Paxos algorithm for solving the distributed consensus problem. Examples of Paxos implementations in the wild include Amazon’s DynamoDB, Google’s Spanner, Microsoft Azure’s Cosmos DB, and Cassandra. But it has a reputation of being difficult to understand.

You can see my FizzBee model of Paxos at https://github.com/lorin/paxos-fizzbee/blob/main/paxos-register.fizz.

What problem does Paxos solve?

Paxos solves what is known as the consensus problem. Here’s how Lamport describes the requirements for conensus.

Assume a collection of processes that can propose values. A consensus algorithm ensures that a single one among the proposed values is chosen. If no value is proposed, then no value should be chosen. If a value has been chosen, then processes should be able to learn the chosen value.

I’ve always found the term chosen here to be confusing. In my mind, it invokes some agent in the system doing the choosing, which implies that there must be a process that is aware of which value is the chosen consensus value once it the choice has been made. But that isn’t actually the case. In fact, it’s possible that a value has been chosen without any one process in the system knowing what the consensus value is.

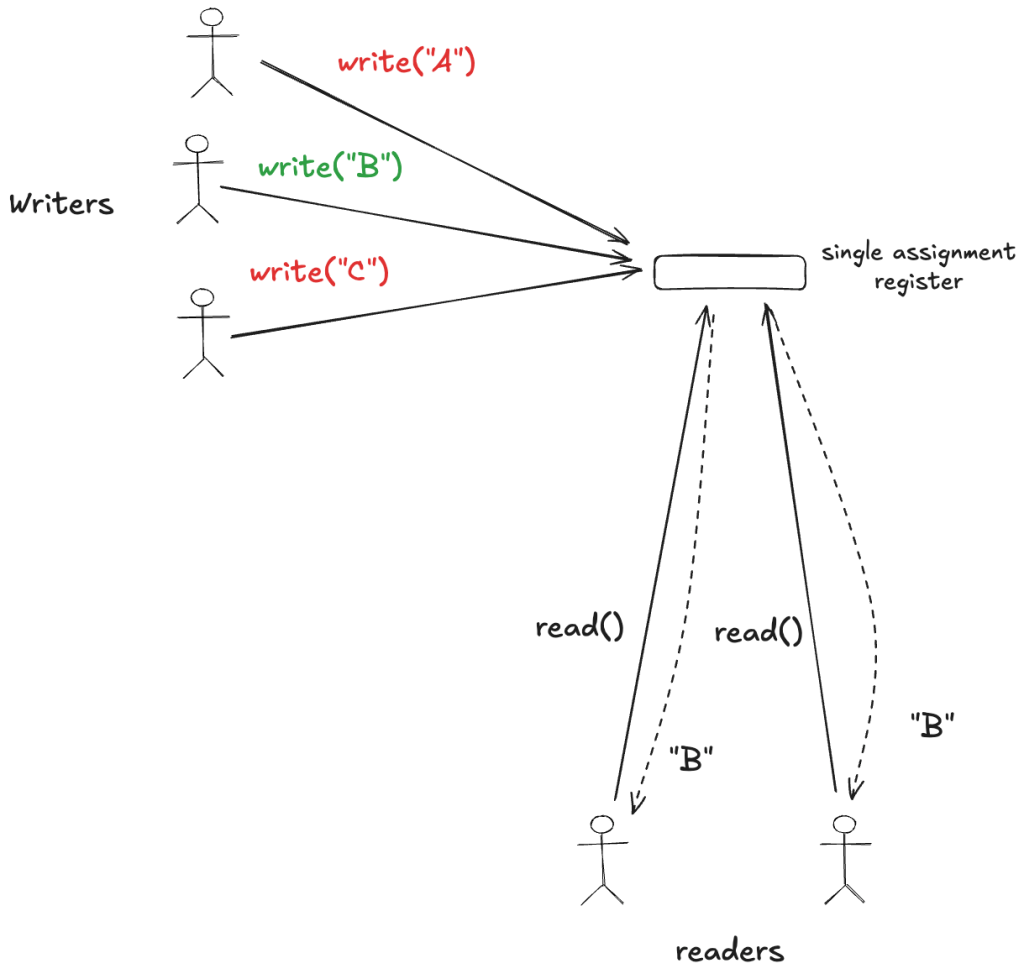

One way to verify that you really understand a concept is to try to explain it in different words. So I’m going to recast the problem to implementing a particular abstract data type: a single-assignment register.

Single assignment register

A register is an abstract data type that can hold a single value. It supports two operations: read and write. You can think of a register like a variable in a programming language.

A single assignment register that can only be written to once. Once a client writes to the register, all future writes will fail: only reads will succeed. The register starts out with a special uninitialized value, the sort of thing we’d represent as NULL in C or None in Python.

If the register has been written to, then a read will return the written value.

Some things to note about the specification for our single assignment register:

- We doesn’t say anything about which write should succeed, we only care that at most one write succeeds.

- The write operations don’t return a value, so the writers don’t receive information about whether the write succeeded. The only way to know if a write succeeded is to perform a read.

Instead of thinking of Paxos as a consensus algorithm, you can think of it as implementing a single assignment register. The chosen value is the value where the write succeeds.

I used Lamport’s Paxos Made Simple paper as my guide for modeling the Paxos algorithm. Here’s the mapping between terminology used in that paper and the alternate terminology that I’m using here.

| Paxos Made Simple paper | Single assignment register (this blog post) |

| choosing a value | quorum write |

| proposers | writers |

| acceptors | storage nodes |

| learners | readers |

| accepted proposal | local write |

| proposal number | logical clock |

As a side note: if you ever wanted to practice doing a refinement mapping with TLA+, you could take one of the existing TLA+ Paxos models and see if you can define a refinement mapping to a single assignment register.

Making our register fault-tolerant with quorum write

One of Paxos’s requirements is that it is fault tolerant. That means a solution that implements a single assignment register using a single node isn’t good enough, because that node might fail. We need multiple nodes to implement our register:

If you’ve ever used a distributed database like DynamoDB or Cassandra, then you’re likely familiar with how they use a quorum strategy, where a single write or read may resulting in queries against multiple database nodes.

You can think of Paxos as implementing a distributed database that consists of one single assignment register, where it implements quorum writes.

The way these writes work are:

- The writer selects a quorum of nodes to attempt to write to: this is a set of nodes that must contain at least a majority. For example, if the entire cluster contains five nodes, then a quorum must contain at least three.

- If the writer attempts to write to every node in the quorum it has selected.

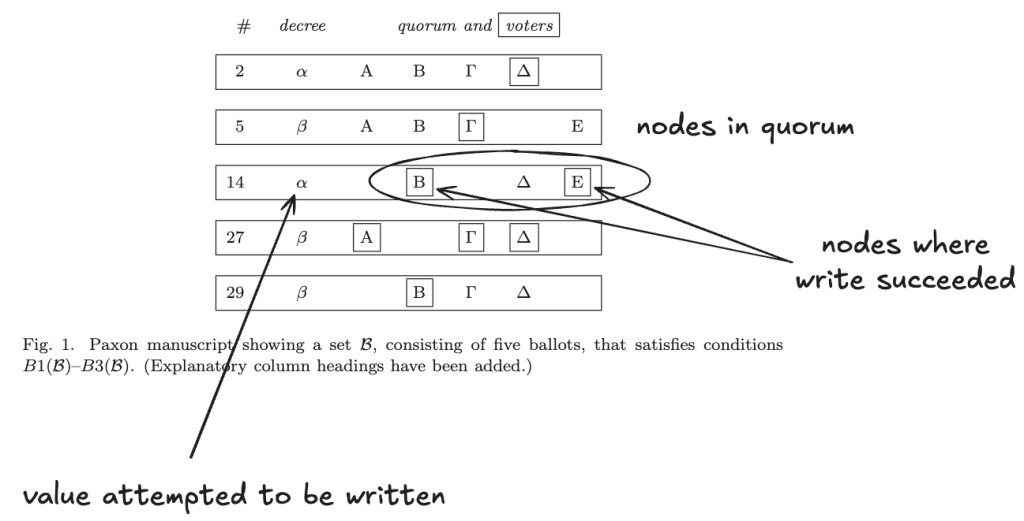

In Lamport’s original paper that introduced Paxos, The Part-Time Parliament, he showed a worked out example of a Paxos execution. Here’s that figure, with some annotations that I’ve added to describe it in terms of a single assignment quorum write register.

In this example, there are five nodes in the cluster, designated by Greek letters {Α,Β,Γ,Δ,Ε}.

The number (#) column acts as a logical clock, we’ll get to that later.

The decree column shows the value that a client attempts to write. In this example, there are two different values that clients attempt to write: {α,β}.

The quorum and voters columns indicate which nodes are in the quorum that the writer selected. A square around a node indicates that the write succeeded against that node. In this example, a quorum must contain at least three nodes, though it can have more than three: the quorum in row 5 contains four nodes.

Under this interpretation, in the first row, the write operation with the argument α succeeded on node Δ: there was a local write to node Δ, but there was not yet a quorum write, as it only succeeded on one node.

While the overall algorithm implements a single assignment register, the individual nodes themselves do not behave as single assignment registers: the value written to a node in can potentially change during the execution of the Paxos algorithm. In the example above, in row 27, the value β is successfully written to node Δ, which is different from the value α written to that node in row 2.

Safety condition: can’t change a majority

The write to our single assignment register occurs when there’s a quorum write: when a majority of the nodes have the same value written to them. To enforce single assignment, we cannot allow a majority of nodes to see a different written value over time.

Here’s how I expressed that safety condition in FizzBee, where written_values is a history variable that keeps track of which values were successfully written to a majority of nodes.

# Only a single value is written

always assertion SingleValueWritten:

return len(written_values)<=1

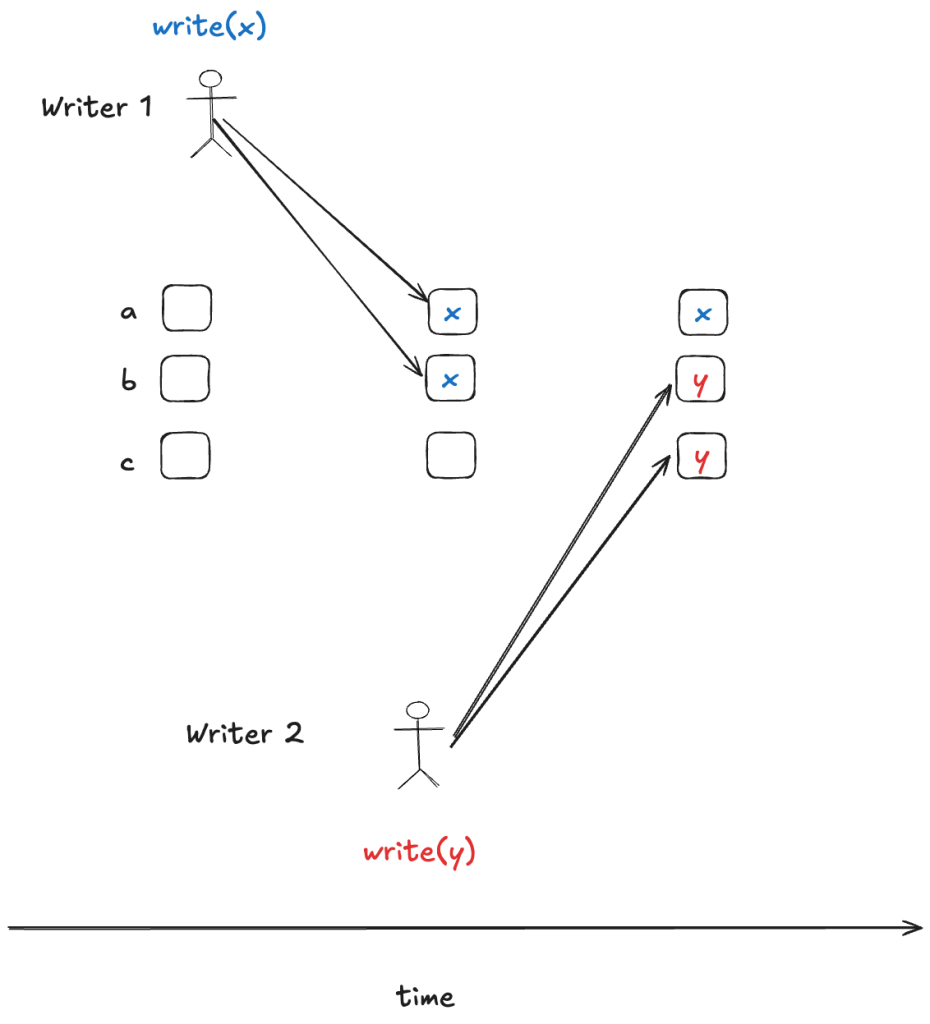

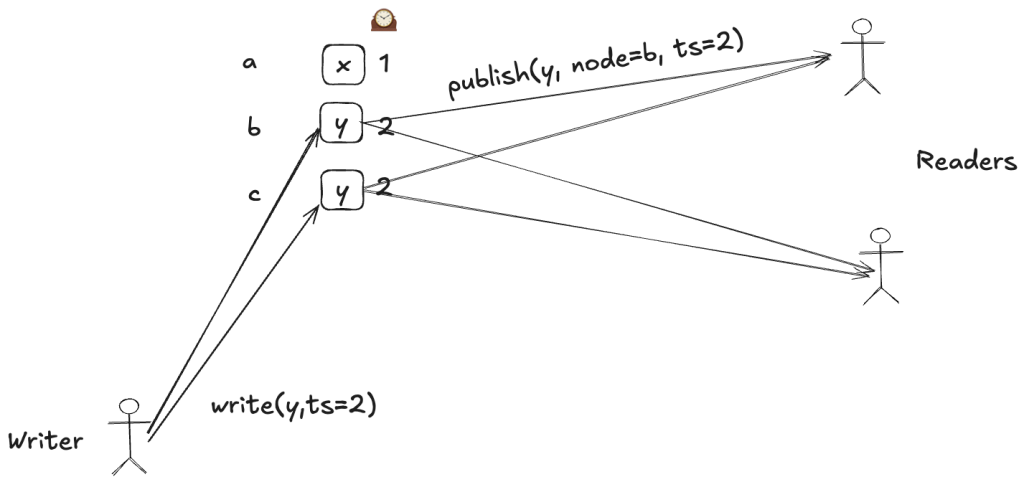

Here’s an example scenario that would violate that invariant:

In this scenario, there are three nodes {a,b,c} and two writers. The first writer writes the value x to nodes a and b. As a consequence, x is the value written to the majority of nodes. The second writer writes the value y to nodes b and c, and so y becomes the value written to the majority of nodes. This means that the set of values written is: {x, y}. Because our single assignment register only permits one value to be registered, the algorithm must ensure that a scenario like this does not occur.

Paxos uses two strategies to prevent writes that could change the majority:

- Read-before-write to prevent clobbering a known write

- Unique, logical timestamps to prevent concurrent writes

Read before write

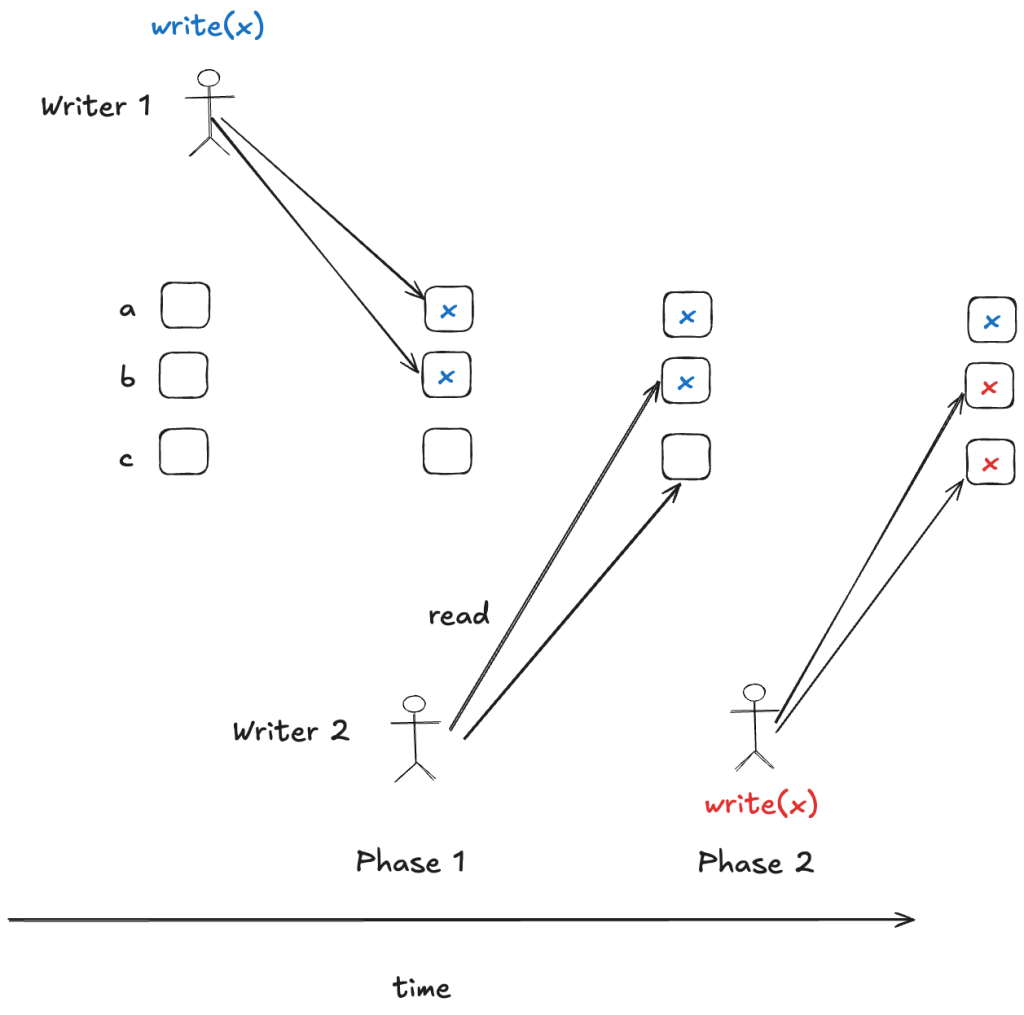

In Paxos, a writer will first do a read against all of the nodes in its quorum. If any node already contains a write, the writer will use the existing written value.

Preventing concurrent writes

The read-before-write approach works if writer 2 tries to do a write after writer 1 has completed its write. But if the writes overlap, then this will not prevent one writer from clobbering the other writer’s quorum write:

Paxos solves this by using a logical clock scheme to ensure that only one concurrent writer can succeed. Note that Lamport doesn’t refer to it as a logical clock, but I found it useful to think of it this way.

Each writer has a local clock which is set to a different value. When the writer makes read or write calls, It passes the time of the clock as an additional argument.

Each storage node keeps a logical clock. This storage node’s clock is updated by a read call: if the timestamp of the read call is later than the storage node’s local clock, then the node will advance its clock to match the read timestamp. The node will reject writes with timestamps that are dated before its clock.

In the example above, node b rejects writer 1’s write because the write has a timestamp of 1, and node b has a logical clock value of 2. As a consequence, a quorum write only occurs when writer 2 completes its write.

Readers

The writes are the interesting part of Paxos, which is where I focused. In my FizzBee model, I chose the simplest way to implement readers: a pub-sub approach where each node publishes out each successful write to all of the readers.

The readers then keep a tally of the writes that have occurred on each node, and when they identify a majority, they record it.

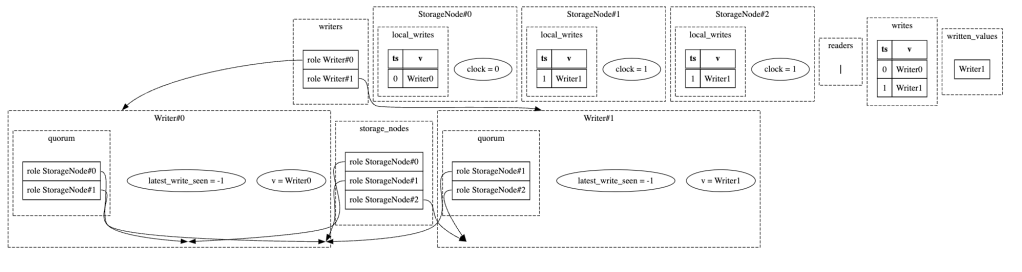

Modeling with FizzBee

For my FizzBee model, I defined three roles:

- Writer

- StorageNode

- Reader

Writer

There are two phases to the writes. I modeled each phase as an action. Each writer uses its own identifier, __id__, as the value to be written. This is the sort of thing you’d do when using Paxos to do leader election.

role Writer:

action Init:

self.v = self.__id__

self.latest_write_seen = -1

self.quorum = genericset()

action Phase1:

unsent = genericset(storage_nodes)

while is_majority(len(unsent)):

node = any unsent

response = node.read_and_advance_clock(self.clock)

(clock_advanced, previous_write) = response

unsent.discard(node)

require clock_advanced

atomic:

self.quorum.add(node)

if previous_write and previous_write.ts > self.latest_write_seen:

self.latest_write_seen = previous_write.ts

self.v = previous_write.v

action Phase2:

require is_majority(len(self.quorum))

for node in self.quorum:

node.write(self.clock, self.v)

One thing that isn’t obvious is that there’s a variable named clock that gets automatically injected into the role when the instance is created in the top-level Init action:

action Init:

writers = []

...

for i in range(NUM_WRITERS):

writers.append(Writer(clock=i))

This is how I ensured that each writer had a unique timestamp associated with it.

StorageNode

The storage node needs to support two RPC calls, one for each of the write phases:

- read_and_advance_clock

- write

It also has a helper function named notify_readers, which does the reader broadcast.

role StorageNode:

action Init:

self.local_writes = genericset()

self.clock = -1

func read_and_advance_clock(clock):

if clock > self.clock:

self.clock = clock

latest_write = None

if self.local_writes:

latest_write = max(self.local_writes, key=lambda w: w.ts)

return (self.clock == clock, latest_write)

atomic func write(ts, v):

# request's timestamp must be later than our clock

require ts >= self.clock

w = record(ts=ts, v=v)

self.local_writes.add(w)

self.record_history_variables(w)

self.notify_readers(w)

func notify_readers(write):

for r in readers:

r.publish(self.__id__, write)

There’s a helper function I didn’t show here called record_history_variables, which I defined to record some data I needed for checking invariants, but isn’t important for the algorithm itself.

Reader

Here’s my FizzBee model for a reader. Note how it supports one RPC call, named publish.

role Reader:

action Init:

self.value = None

self.tallies = genericmap()

self.seen = genericset()

# receive a publish event from a storage node

atomic func publish(node_id, write):

# Process a publish event only once per (node_id, write) tuple

require (node_id, write) not in self.seen

self.seen.add((node_id, write))

self.tallies.setdefault(write, 0)

self.tallies[write] += 1

if is_majority(self.tallies[write]):

self.value = write.v

Generating interesting visualizations

I wanted to generate a trace where there a quorum write succeeded but not all nodes wrote the same value.

I defined an invariant like this:

always assertion NoTwoNodesHaveDifferentWrittenValues:

# we only care about cases where consensus was reached

if len(written_values)==0:

return True

s = set([max(node.local_writes, key=lambda w: w.ts).v for node in storage_nodes if node.local_writes])

return len(s)<=1

Once FizzBee found a counterexample, I used it to generate the following visualizations:

General observations

I found that FizzBee was a good match for modeling Paxos. FizzBee’s roles mapped nicely onto the roles described in Paxos Made Simple, and the phases mapped nicely onto FizzBee’s action. FizzBee’s first-class support for RPC made the communication easy to implement.

I also appreciated the visualizations that FizzBee generated. I found both the sequence diagrams of the model state diagram useful as I was debugging my model.

Finally, I learned a lot more about how Paxos works by going through the exercise of modeling it, as well as writing this blog post to explain it. When it comes to developing a better understanding of an algorithm, there’s no substitute for the act of building a formal model of it and then explaining your model to someone else.

I used to teach Paxos for a university course, and I’m still far from sure I understand it myself, so this is a welcome illustration!

BTW “This clock is updated by read calls, to the most recent timestamp that.” is probably an typo/inaccurancy needing fixing…

Thanks for the copy-edit, that’s been fixed now.