If you work in software, and I say the word server to you, which do you think I mean?

- Software that responds to requests (e.g., http server)

- A physical piece of hardware (e.g., a box that sits in a rack in a data center)

- A virtual machine (e.g., an EC2 instance)

The answer, of course, is it depends on the context. The term server could mean any of those things. The term is ambiguous; it’s overloaded to mean different things in different contexts.

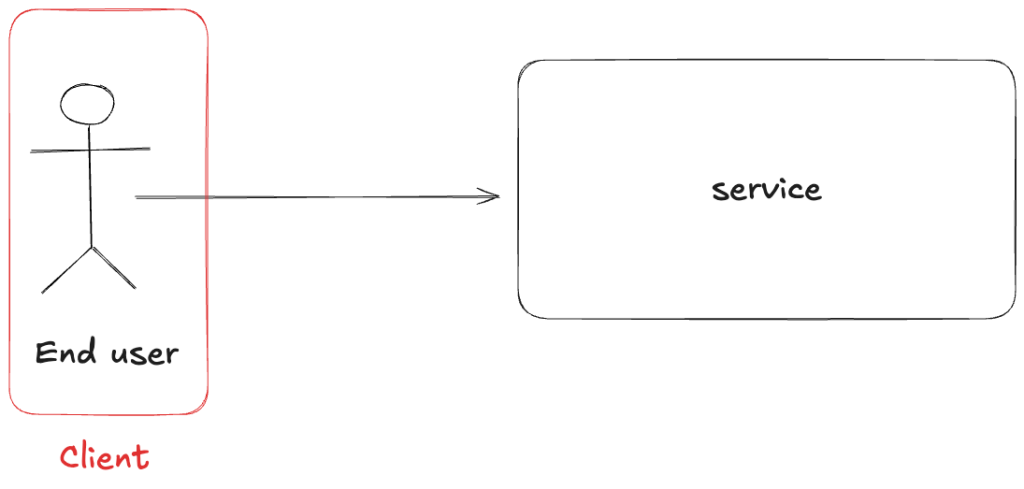

Another example of an overloaded term is service. From the end user’s perspective, the service is the system they interact with:

But if we zoom in on that box labeled service, it might be implemented by a collection of software components, where each component is also referred to as a service. This is sometimes referred to as a service-oriented architecture or a microservice architecture

Amusingly, when I worked at Netflix, people referred to microservices as “services”, but people also referred to all of Netflix as “the service”. For example, instead of saying, “What are you currently watching on Netflix?”, a person would say, “What are you currently watching on the service?”

Yet another example is the term “client”. This could refer to the device that the end-user is using (e.g., web browser, mobile app):

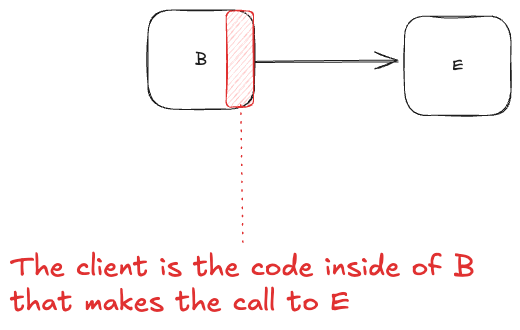

Or it could refer to the caller service in a microservice architecture:

It could also refer to the code in the caller service that is responsible for making the request, typically packaged as a client library.

The fact that the meaning of these terms is ambiguous and context-dependent makes it harder to understand what someone is talking about when the term is used. While the person speaking knows exactly what sense of server, service or client they mean, the person hearing it does not.

The ambiguous meaning of these terms creates all sorts of problems, especially when communicating across different teams, where the meaning of a term used by the client team of a service may be different from the meaning of the term used by the owner of a service. I’m willing to bet that you, dear reader, have experienced this problem at some point in the past when reading an internal tech doc or trying to parse the meaning of a particular slack message.

As someone who is interested in incidents, I’m acutely aware of the problematic nature of ambiguous language during incidents, where communication and coordination play an enormous role in effective incident handling. But it’s not just an issue for incident handling. For example, Eric Evans advocates the use of ubiquitous language in software design. He pushes for consistent use of terms across different stakeholders to reduce misunderstandings.

In principle, we could all just decide to use more precise terminology. This would make it easier for listeners to understand the intent of speakers, and would reduce the likelihood of problems that stem from misunderstandings. At some level, this is the role that technical jargon plays. But client, server and service are technical jargon, and they’re still ambiguous. So, why don’t we just use even more precise language?

The problem is that expressing ourselves in unambiguous isn’t free: it costs the speaker additional effort to be more precise. As a trivial example, microservice is more precise than service, but it takes twice as long as to say, and it takes an additional five letters to write. Those extra syllables and letters are a cost to the speaker. And, all other things being equal, people prefer expending less effort than more effort. This is why we don’t like being on the receiving end of ambiguous language, because we have to put more effort into resolving the ambiguity through context clues.

The cost of precision to the speaker is clear in the world of computer programming. Traditional programming languages require an extremely high degree of precision on behalf of the coder. This sets a very high bar for being able to write programs. On the other hand, modern generative AI tools are able to take natural language inputs as specifications which are orders of magnitude less precise, and turn them into programs. These tools are able to process ambiguous inputs in ways that regular programming languages simply cannot. The cost in effort is much lower for the vibe programmer. (I will leave evaluation of the outcomes of vibe programming as an exercise for the reader).

Ultimately, the degree in precision in communication is a tradeoff: an increase in precision means less effort for the listener and less risk of misunderstanding, at a cost of more effort for the speaker. Because of this tradeoff, we shouldn’t expect the equilibrium point to be at maximal precision. Instead, it’s somewhere in the middle. Ideally, it would be where we minimize the total effort. Now, I’m not a cognitive scientist, but this is a theory that has been advanced by cognitive scientists. For example, see the paper The communicative function of ambiguity in language by Steven T. Piantadosi, Harry Tily, and Edward Gibson. I touched on the topic of ambiguity more generally in a previous post the high cost of low ambiguity.

We often ask “why are people doing X instead of the obviously superior Y“. This is an example of how we are likely missing the additional costs of choosing to do Y over X. Just because we don’t notice those costs doesn’t mean they aren’t there. It means we aren’t looking closely enough.