In the software operations world, if your service is successful, then eventually the load on it is going to increase to the point where you’ll need to give that services more resources. There are two strategies for increasing resources: scale up and scale out.

Scaling up means running the service on a beefier system. This works well, but you can only scale up so much before you run into limits of how large a machine you have access to. AWS has many different instance types, but there will come a time when even the largest instance type isn’t big enough for your needs.

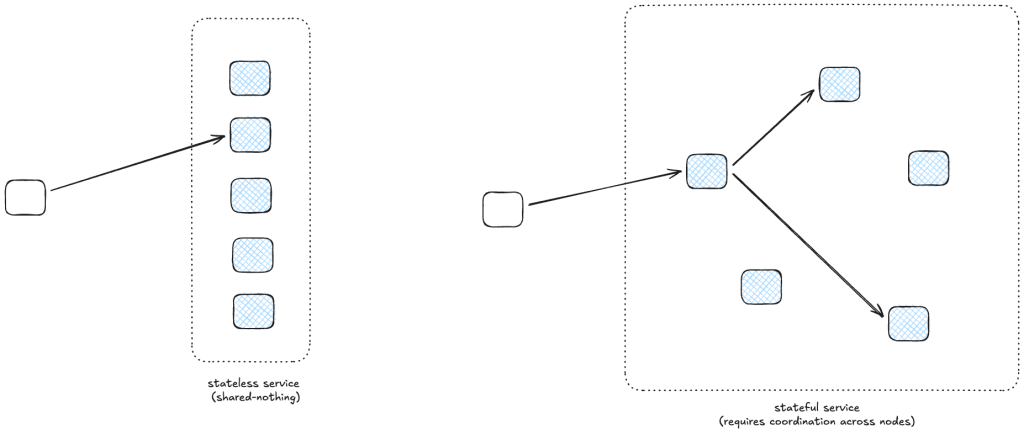

The alternative is scaling out: instead of running your service on a bigger machine, you run your service on more machines, distributing the load across those machines. Scaling out is very effective if you are operating a stateless, shared-nothing microservice: any machine can service any request. It doesn’t work as well for services where the different machines need to access shared state, like a distributed database. A database is harder to scale out because the machines need to share state, which means they need to coordinate with each other.

Once you have to do coordination, you no longer get a linear improvement in capacity based on the number of machines: doubling the number of machines doesn’t mean you can handle double the load. This comes up in scientific computing applications, where you want to run a large computing simulation, like a climate model, on a large-scale parallel computer. You can run independent simulations very easily in parallel, but if you want to run an individual simulation more quickly, you need to break up the problem in order to distribute the work across different processors. Imagine modeling the atmosphere as a huge grid, and dividing up that grid and having different processors work on simulating different parts of the grid. You need to exchange information between processors at the grid boundaries, which introduces the need for coordination. Incidentally, this is why supercomputers have custom networking architectures, in order to try to reduce these expensive coordination costs.

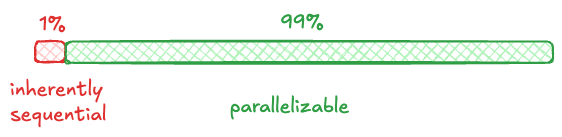

In the 1960s, the American computer architect Gene Amdahl made the observation that the theoretical performance improvement you can get from a parallel computer is limited by the fraction of work that cannot be parallelized. Imagine you have a workload where 99% of the work is amenable to parallelization, but 1% of it can’t be parallelized:

Let’s say that running this workload on a single machine takes 100 hours. Now, if you ran this on an infinitely large supercomputer, the green part above would go from 99 hours to 0. But you are still left with the 1 hour of work that you can’t parallelize, which means that you are limited to 100X speedup no matter how large your supercomputer is. The upper limit on speedup based on the amount of the workload that is parallelizable is known today as Amdahl’s Law.

But there’s another law about scalability on parallel computers, and it’s called Gustafson’s Law, named for the American computer scientist John Gustafson. Gustafson observed that people don’t just use supercomputers to solve existing problems more quickly. Instead, they exploit the additional resources available in supercomputers to solve larger problems. The larger the problem, the more amenable it is to parallelization. And so Gustafson proposed scaled speedup as an alternative metric, which takes this into account. As he put it: in practice, the problem size scales with the number of processors.

And that brings us to LLM-based coding agents.

AI coding agents improve programmer productivity: they can generate working code a lot more quickly than humans can. As a consequence of this productivity increase, I think we are going to find the same result that Gustafson observed at Sandia National Labs: that people will use this productivity increase in order to do more work, rather than simply do the same amount of coding work with fewer resources. This is a direct consequence of the law of stretched systems from cognitive systems engineering: systems always get driven to their maximum capacity. If coding agents save you time, you’re going to be expected to do additional work with that newfound time. You launch that agent, and then you go off on your own to do other work, and then you context-switch back when the agent is ready for more input.

And that brings us back to Amdahl: coordination still places a hard limit on how much you can actually do. Another finding from cognitive systems engineering is that coordination costs, continually. Coordination work require requires continuous investment of effort. The path we’re on feels the work of software development is shifting from direct coding to a human coordinating with a single agent to a human coordinating work among multiple agents working in parallel. It’s possible that we will be able to fully automate this coordination work, by using agents to do the coordination. Steve Yegge’s Gas Town project is an experiment to see how far this sort of automated agent-based coordination can go. But I’m pessimistic on this front. I think that we’ll need human software engineers to coordinate coding agents for the foreseeable future. And the law of stretched systems teaches us that these multi-coding-agent systems are going to keep scaling up the number of agents until the human coordination work becomes the fundamental bottleneck.