One of the surprising (at least to me) consequences of the fall of Twitter is the rise of LinkedIn as a social media site. I saw some interesting posts I wanted to call attention to:

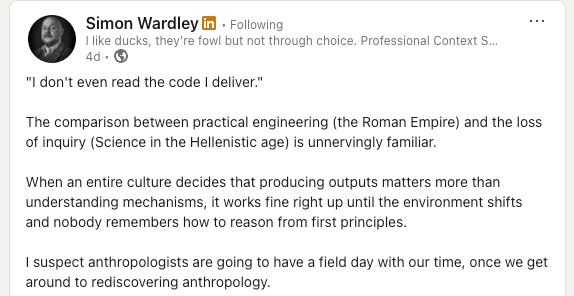

First, Simon Wardley on building things without understanding how they work:

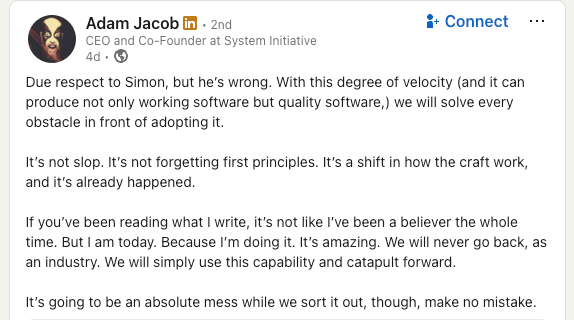

Here’s Adam Jacob in response:

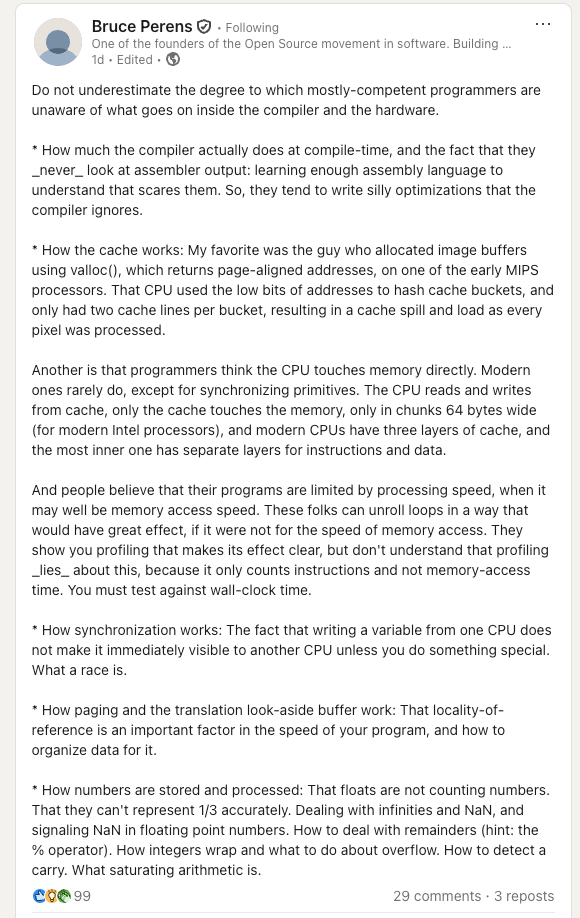

And here’s Bruce Perens, whose post is very much in conversation with them, even though he’s not explicitly responding to either of them.

Finally, here’s the MIT engineering professor Louis Bucciarelli from his book Designing Engineers, written back in 1994. Here I’m just copying and paste the quotes from my previous post on active knowledge.

A few years ago, I attended a national conference on technological literacy… One of the main speakers, a sociologist, presented data he had gathered in the form of responses to a questionnaire. After a detailed statistical analysis, he had concluded that we are a nation of technological illiterates. As an example, he noted how few of us (less than 20 percent) know how our telephone works.

This statement brought me up short. I found my mind drifting and filling with anxiety. Did I know how my telephone works?

I squirmed in my seat, doodled some, then asked myself, What does it mean to know how a telephone works? Does it mean knowing how to dial a local or long-distance number? Certainly I knew that much, but this does not seem to be the issue here.

No, I suspected the question to be understood at another level, as probing the respondent’s knowledge of what we might call the “physics of the device.”I called to mind an image of a diaphragm, excited by the pressure variations of speaking, vibrating and driving a coil back and forth within a a magnetic field… If this was what the speaker meant, then he was right: Most of us don’t know how our telephone works.

Indeed, I wondered, does [the speaker] know how his telephone works? Does he know about the heuristics used to achieve optimum routing for long distance calls? Does he know about the intricacies of the algorithms used for echo and noise suppression? Does he know how a signal is transmitted to and retrieved from a satellite in orbit? Does he know how AT&T, MCI, and the local phone companies are able to use the same network simultaneously? Does he know how many operators are needed to keep this system working, or what those repair people actually do when they climb a telephone pole? Does he know about corporate financing, capital investment strategies, or the role of regulation in the functioning of this expansive and sophisticated communication system?

Does anyone know how their telephone works?

There’s a technical interview question that goes along the lines of: “What happens when you type a URL into your browser’s address bar and hit enter?” You can talk about what happens at all sorts of different levels (e.g., HTTP, DNS, TCP, IP, …). But does anybody really understand all of the levels? Do you know about the interrupts that fire inside of your operating system when you actually strike the enter key? Do you know which modulation scheme being used by the 802.11ax Wi-Fi protocol in your laptop right now? Could you explain the difference between quadrature amplitude modulation (QAM) and quadrature phase shift keying (QPSK), and could you determine which one your laptop is currently using? Are you familiar with the relaxed memory model of the ARM processor? How garbage collection works inside of the JVM? Do you understand how the field effect transistors inside the chip implement digital logic?

I remember talking to Brendan Gregg about how he conducted technical interviews, back when we both worked at Netflix. He told me that he was interested in identifying the limits of a candidate’s knowledge, and how they reacted when they reached that limit. So, he’d keep asking deeper questions about their area of knowledge until they reached a point where they didn’t know anymore. And then he’d see whether they would actually admit “I don’t know the answer to that”, or whether they would bluff. He knew that nobody understood the system all of the way down.

In their own ways, Wardley, Jacob, Perens, and Bucciarelli are all correct.

Wardley’s right that it’s dangerous to build things where we don’t understand the underlying mechanism of how they actually work. This is precisely why magic is used as an epithet in our industry. Magic refers to frameworks that deliberately obscure the underlying mechanisms in service of making it easier to build within that framework. Ruby on Rails is the canonical example of a framework that uses magic.

Jacob is right that AI is changing the way that normal software development work gets done. It’s a new capability that has proven itself to be so useful that it clearly isn’t going away. Yes, it represents a significant shift in how we build software, it moves us further away from how the underlying stuff actually works, but the benefits exceed the risks.

Perens is right that the scenario that Wardley fears has, in some sense, already come to pass. Modern CPU architectures and operating systems contain significant complexity, and many software developers are blissfully unaware of how these things really work. Yes, they have mental models of how the system below them works, but those mental models are incorrect in fundamental ways.

Finally, Bucciarelli is right that systems like telephony are so inherently complex, have been built on top of so many different layers in so many different places, that no one person can ever actually understand how the whole thing works. This is the fundamental nature of complex technologies: our knowledge of these systems will always be partial, at best. Yes, AI will make this situation worse. But it’s a situation that we’ve been in for a long time.

In 1977, I was part of a team at BNR, working on the first all-digital telephone switch (DMS-100). We thought that we could apply our ComputerScience knowledge to build a nicely layered set of abstractions in an elegant framework. And we failed in our attempt to encapsulate a century of analog telephony engineering … so, we were loaned a veteran telephony engineer, and all day programmers went to his office and said “George, we have a thingamabob connected via SF signalling to a whatchamacallit, and the thingamobob does 3 off-hooks and an on-hook and the watchmacallit responds … and then … and then … and what happens next?” and George would think for a bit or consult from his bookshelf of binders and give the answer, which was duly incorporated into the code that was becoming more byzantine every day.

At one point, I was asked to interface an 1894 Stromberg-Carlson switchboard to our fancy digital switch (telephone companies were loathe to retire equipment that had been fully depreciated).

(The DMS-100 operating system and programming languages, however, were elegant, as was the overall architecture of the system. (For example, we were using relational databases before Oracle; and a OOP before C++.) But the signalling was a hodgepodge of special cases)

Nobody knows how the whole system works, but at least everybody should know the part of the system they are contributing to.

Being an engineer I am used to be expert of the very layer of the stack I work on, knowing something of the adjacent layers, mostly ignoring how the rest work.

Now that LLMs write my very code, what is the part that I’m supposed to master? I think the table is still shifting and everybody is failing to grasp where it will stabilize. Analogies with past shifts aren’t helping either.

But all of these deep magical sections are confined, abstracted by people who know their fields good enough. Not everyone needs to know all details of all subsystems, just knowing how they “promise” to work is enough. If it doesn’t work like it supposed to, you report it to people who know these systems.That’s the way how things worked so far.

LLMs change this on a fundamental level: People who are “supposed to know” a certain part figured out you don’t actually have to, you can just make “the thing” do it for you. And this means something else, I suspect that’s the thing people mainly complaining about.

Spot on.The executive who doesn’t look at code level detail is relying on a chain of people who do. The CTO can read code. The engineering managers came up through the ranks writing it. The senior developers review the juniors. Somewhere in that chain, even when it extends to outside vendors that comprehension exists or is at least notionally recoverable. Yes, we still end up with the legacy problem and whilst many organisations find that comprehension hard to recover, we still can and still do.In this light, the executive is outsourcing attention, comprehension still remains in the chain.The concern with LLM/GPT generated code isn’t that developers are delegating because developers have always delegated to libraries, frameworks and even compilers. It’s that the delegation has extended to comprehension. There is no chain, just systems that cannot explain their reasoning beyond generating plausible sounding explanations for code it has already produced.The reasoning, the understanding is lost. And without that, so is learning.https://www.linkedin.com/posts/simonwardley_x-how-many-executives-are-looking-at-code-activity-7426577558827216897-5Y0G

to me this is the difference between programming, any sort of engineering and ‘vibing’. In a team, if you aren’t in control of the entire stack

You can do either a combination of both to a great success, but to be able to actually maintain the project, hand it off between different humans, departments or technology, I need a reasonably well defined interface.

What that interface is matters a lot in this telephone example(haven’t heard it before, it’s brilliant! Thanks). Average user interfaces with what they’re sold and rarely much beyond that. Maybe, maybe transfer media over a cable but really how many people do you know that go beyond “oh it just appears in my app everywhere it’s so ez M8”. And reading this I assume you may be a nerd.

Average nerd will maybe have tried interfacing with a modern telephone with some terminal or flashing it and what not. Even things like SyncThing are considered advanced because it takes more than “log in here with yer social media button. Also we’ll throw you a bucket of notifications so you remember this app exists”.

It’s not meant to be an insult, it’s how things and interfaces have been designed for a while and habits form easily. I hardly know how to control a microwave.

My point is the same applies to whatever you’re trying to create. I’m a full stack developer but that really means I know back end development really well and constantly research and take forever when I need to work beyond my “primary” interface. From understanding my framework and front end enough to make it work being basically the secondary layer, servers it runs on I know a bit less yet, and then networks, hardware and what not go in the same category as case engines and what not. Might mess around with it, take it apart but what happens next…

Neither we, and at this point nor anytime soon the AI can possibly know everything. And as long as we can use others’ contributions as foundation so we can focus on our own skill, not much seems to change with AI from that perspective. As long as you decide to trust what it provides you, it’s just like anyone else’s promise of quality.

I like knowing my interfaces and I like to trust them. I definitely appreciate the grunt of work I can get from AI, yet only after using it to some extent for years I found *one* I have seen convincing results where I can focus on it’s interfaces, test it thoroughly and not discard nearly everything beyond basic autocomplete.

The idea of letting AI do it’s thing and only looking at the result is hardly different than being a user of anything else. I guess it works well with the whole “good enough” idea – if the interface you’ll interact with in the end is good enough for you, then by all means you don’t need to understand it deeper. You may struggle to develop it further, but more AI will make another good enough update.

to me this is the difference between programming, any sort of engineering and ‘vibing’. In a team, if you aren’t in control of the entire stack

You can do either a combination of both to a great success, but to be able to actually maintain the project, hand it off between different humans, departments or technology, I need a reasonably well defined interface.

What that interface is matters a lot in this telephone example(haven’t heard it before, it’s brilliant! Thanks). Average user interfaces with what they’re sold and rarely much beyond that. Maybe, maybe transfer media over a cable but really how many people do you know that go beyond “oh it just appears in my app everywhere it’s so ez M8”. And reading this I assume you may be a nerd.

Average nerd will maybe have tried interfacing with a modern telephone with some terminal or flashing it and what not. Even things like SyncThing are considered advanced because it takes more than “log in here with yer social media button. Also we’ll throw you a bucket of notifications so you remember this app exists”.

It’s not meant to be an insult, it’s how things and interfaces have been designed for a while and habits form easily. I hardly know how to control a microwave.

My point is the same applies to whatever you’re trying to create. I’m a full stack developer but that really means I know back end development really well and constantly research and take forever when I need to work beyond my “primary” interface. From understanding my framework and front end enough to make it work being basically the secondary layer, servers it runs on I know a bit less yet, and then networks, hardware and what not go in the same category as case engines and what not. Might mess around with it, take it apart but what happens next…

Neither we, and at this point nor anytime soon the AI can possibly know everything. And as long as we can use others’ contributions as foundation so we can focus on our own skill, not much seems to change with AI from that perspective. As long as you decide to trust what it provides you, it’s just like anyone else’s promise of quality.

I like knowing my interfaces and I like to trust them. I definitely appreciate the grunt of work I can get from AI, yet only after using it to some extent for years I found *one* I have seen convincing results where I can focus on it’s interfaces, test it thoroughly and not discard nearly everything beyond basic autocomplete.

The idea of letting AI do it’s thing and only looking at the result is hardly different than being a user of anything else. I guess it works well with the whole “good enough” idea – if the interface you’ll interact with in the end is good enough for you, then by all means you don’t need to understand it deeper. You may struggle to develop it further, but more AI will make another good enough update.

The problem is not that an individual does not understand the entire chain, that has never been an issue. The executive who doesn’t look at code level detail is relying on a chain of people who do. The CTO can read code. The engineering managers came up through the ranks writing it. The senior developers review the juniors. Somewhere in that chain, even when it extends to outside vendors that comprehension exists or is at least notionally recoverable. Yes, we still end up with the legacy problem and whilst many organisations find that comprehension hard to recover, we still can and still do.

In this light, the executive is outsourcing attention, comprehension still remains in the chain.

The concern with LLM/GPT generated code isn’t that developers are delegating because developers have always delegated to libraries, frameworks and even compilers. It’s that the delegation has extended to comprehension. There is no chain, just systems that cannot explain their reasoning beyond generating plausible sounding explanations for code it has already produced.

The reasoning, the understanding is lost. And without that, so is learning.

https://www.linkedin.com/posts/simonwardley_x-how-many-executives-are-looking-at-code-activity-7426577558827216897-5Y0G

I was engrossed in the reading, until I hit your comment about AI: “it moves us further away from how the underlying stuff actually works, but the benefits exceed the risks.”

This whole article is about how we don’t know “how the whole system works”, then you write that “the benefits exceed the risks”. Do they? Do you know this FOR SURE? How do you know this?

It was just such a jarring statement on the tail end of the cautionary outlook of the article.

Well, yes, nobody knows how the whole system works. This does not mean that there is no value in knowing things. And LLMs encourage people to move towards a future where nobody knows how *anything* works. And they don’t care, because they can keep turning the crank and the machine spits out more code that might even work.

As Wardley points out in the comments, this crank-turning process sidesteps most of the learning process. So… I don’t know where that road leads, but I certainly don’t want to be on it. It’s antithetical to the love of the craft, and we may end up with a generation of LLM users who don’t know how anything works, but can build towers of clay very quickly.

There are shortcuts, hacks in life and you should use them, especially when it comes to people. So, about the LinkedIn comments, it’s so easy to see who is right.

Really discern Adam Jacob’s profile pic and believe what he is telling you about himself.

I take the Object-Oriented view of things: The important aspect is the space between interacting components, their interfaces, their specifications. This is why old and new hardware can coexist in the telephone network as Peter Ludemann mentioned, and the lack of detail here would be the cause of any troubles there.

Of course, far too many programmers have been convinced that imperfection is necessary in software, a very convenient excuse for their incompetence that would have them legally liable in a decent society. Not all programming can be compared to engineering, not even most, and I’d rather compare it to math, but engineers operate under very real punishments for negligence.

This has been an interesting article, ruined by the following nonsense: “It’s a new capability that has proven itself to be so useful that it clearly isn’t going away.”

I’m a Lisp hacker, an APL afficianado, and an Ada programmer. I also have a tool for hardcore machine code hacking. In any case, this neural network nonsense is worthless to me. The appeal of this to those in charge is the allure of removing everyone else, and the appeal to everyone else is the siren song of doing without any associated learning. This largely will go away like a bad dream, except for the scams and whatnot it enables, once the money runs out. At the very least, the people calling it inevitable will shut up.