Justine Tunney recently wrote a blog post titled The Fastest Mutexes where she describes how she implemented mutexes in Cosmopolitan Libc. The post discusses how her implementation uses futexes by way of Mike Burrows’s nsync library. From her post

nsync enlists the help of the operating system by using futexes. This is a great abstraction invented by Linux some years ago, that quickly found its way into other OSes. On MacOS, futexes are called ulock. On Windows, futexes are called WaitOnAddress(). The only OS Cosmo supports that doesn’t have futexes is NetBSD, which implements POSIX semaphores in kernelspace, and each semaphore sadly requires creating a new file descriptor. But the important thing about futexes and semaphores is they allow the OS to put a thread to sleep. That’s what lets nsync avoid consuming CPU time when there’s nothing to do.

Before I read this post, I had no idea what futexes were or how they worked. I figured a good way to learn would be to model them in TLA+.

Note: I’m going to give a simplified account of how futexes work. In addition, I’m not an expert on this topic. In particular, I’m not a kernel programmer, so there may be important details I get wrong here.

Mutexes

Readers who have done multithreaded programming before are undoubtedly familiar with mutexes: they are a type of lock that allows the programmer to enforce mutual exclusion, so that we can guarantee that at most one thread accesses a resource, such as a shared variable.

The locking mechanism is implemented by the operating system: locking and unlock the mutex ultimately involves a system call. If you were programming in C on a Unix-y system like Linux, you’d use the pthreads API to access the mutex objects. Which pthreads implementation you use (e.g., glibc, musl) will make the relevant system calls for you.

#include <pthread.h>

...

// create a mutex

pthread_mutex_t mutex = PTHREAD_MUTEX_INITIALIZER;

pthread_mutex_lock(&mutex);

// mutex is now locked

pthread_mutex_unlock(&mutex);

// mutex is now unlocked

Modeling a mutex in TLA+

Before we get into futexes, let’s start off by modeling desired behavior of a mutex in TLA+. I’ll use the PlusCal algorithm language for my model, which can be translated directly to a TLA+ model (see my mutex.tla file)

---- MODULE mutex ----

CONSTANT Processes

(*--algorithm MutualExclusion

variables lock = {};

process proc \in Processes

begin

ncs: skip;

acq: await lock = {};

lock := {self};

cs: skip;

rel: lock := lock \ {self};

goto ncs;

end process;

end algorithm;

*)

Modeling threads (Processes)

This model defines a fixed set of Processes. You should really think of these as threads, but there’s a convention in academia to refer to them as processes, so I used that convention. You can think of Processes in this model as a set of threads ids.

Modeling the lock

This model has only explicit variable, named lock, which is my model for the mutex lock. I’ve modeled it as a set. When the lock is free, the set is empty, and when the lock is held by a process, the set contains a single element, the process id.

Process states

PlusCal models also have an implicit variable, pc for program counter. The program counter indicates which state each process is in.

Each process can be in one of four states. We need to give a label to each of these states in our model.

| Label | Description |

|---|---|

| ncs | in the non-critical section (lock is not held) |

| acq | waiting to acquire the lock |

| cs | in the critical section (lock is held) |

| rel | releasing the lock |

We want to make sure that two processes are never in the critical section at the same time. We can express this desired property in TLA+ like this:

InCriticalSection(p) == pc[p] = "cs"

MutualExclusion == \A p1,p2 \in Processes : InCriticalSection(p1) /\ InCriticalSection(p2) => p1 = p2

We can specify MutualExclusion as an invariant and use the TLC model checker to verify that our specification satisfies this property. Check out mutex.cfg for how to configure TLC to check the invariant.

Overhead of traditional mutexes

With a traditional mutex, the application make a system call every time the mutex is locked or unlocked. If the common usage pattern for an application is that there’s only one thread that tries to take the mutex, then you’re paying a performance penalty for having to execute those system calls. If the mutex is being acquired and released in a tight loop, then the time that goes to servicing the system calls could presumably be a substantial fraction of the execution time of the loop.

for(...) {

pthread_mutex_lock(&mutex);

// do work here

pthread_mutex_unlock(&mutex);

}

I don’t know how high these overheads are in practice, but Justine Tunney provides some numbers in her blog post as well as a link to Mark Waterman’s mutex shootout with more performance numbers.

Ideally, we would only pay the performance penalty for system calls when the mutex was under contention, when there were multiple threads that were trying to acquire the lock.

Futexes: avoid the syscalls where possible

Futexes provide a mechanism for avoiding system calls for taking a mutex lock in cases where the lock is not under contention.

More specifically, futexes provide a set of low-level synchronization primitives. These primitives allow library authors to implement mutexes in such a way that they avoid making system calls when possible. Application programmers don’t interact with futexes directly, they’re hidden behind APIs like pthread_mutex_lock.

Primitives: wait and wake

The primary two futex primitives are a wait system call and a wake system call. Each of them take an integer pointer as an argument, which I call futex. Here’s a simplified C function prototype for each of them.

void futex_wait(int *futex);

void futex_wake(int *futex);

(Actual versions of these return status codes, but I won’t be using those return codes in this blog post).

Note that the futex_wait prototype shown above is incomplete: it needs to take an additional argument to guarantee correctness, but we’ll get to that later. I want to start off by providing some intuition on how to use futexes.

When a thread calls the futex_wait system call, the kernel puts the thread to sleep until another thread calls futex_wake with the same futex argument.

Using primitives to build mutexes that avoid system calls

OK, so how do we actually use these things to create mutexes?

Here’s a naive (i.e., incorrect) implementation of lock and unlock functions that implement mutual exclusion using the futex calls. The lock function checks if the lock is free. If it is, it takes the lock, otherwise it waits to be woken up and then tries again.

#define FREE 0

#define ACQUIRED 1

#define CONTENDED 2

void futex_wait(int *futex);

void futex_wake(int *futex);

/**

* Try to acquire the lock. On failure, wait and then try again.

*/

void lock(int *futex) {

bool acquired = false;

while (!acquired) {

if (*futex == FREE) {

*futex = ACQUIRED;

acquired = true;

}

else {

*futex = CONTENDED;

futex_wait(futex, CONTENDED);

}

}

}

/**

* Release lock, wake threads that are waiting on lock

*/

void unlock(int *futex) {

int prev = *futex;

*futex = FREE;

if(prev == CONTENDED) {

futex_wake(futex);

}

}

Note that futex is just an ordinary pointer. In the fast path, the lock function just sets the futex to ACQUIRED, no system call is necessary. It’s only when the futex is not free that it has to make the futex_wait system call.

Similarly, on the unlock side, it’s only when the futex is in the CONTENDED state that the futex_wake system call happens.

Now’s a good time to point out that futex is short for fast userspace mutex. The reason it’s fast is because we can (sometimes) avoid system calls. And the reason we are able to avoid system calls is that, in the fast path, the threads coordinate by modifying a memory location that is accessible in userspace. By userspace, we mean that our futex variable is just an ordinary pointer that the threads all have direct access to: no system call is required to modify it.

By contrast, when we call futex_wait and futex_wake, the kernel needs to read and modify kernel data structures, hence a system call is required.

The code above should provide you with an intuition of how futexes are supposed to work. The tricky part is writing the algorithm in such a way as to guarantee correctness for all possible thread schedules. There’s a reason that Ulrich Drepper wrote a paper titled Futexes are Tricky: it’s easy to get the lock/unlock methods wrong.

Why futex_wait needs another agument

There are many potential race conditions in our initial lock/unlock implementation, but let’s focus on one in particular: if the futex gets freed after the lock checks if it’s free, but before calling futex_wait.

Here’s what the scenario looks like (think of the red arrows as being like breakpoints):

We need to prevent the situation where the unlock thread completes after the *futex == FREE check but before the futex_wait system call.

We can prevent this by modifying the futex_wait function prototype to pass the value we expect the futex to have, it looks like this:

void futex_wait(int *futex, int val);

The lock code then looks like this instead:

void lock(int *futex) {

if(*futex == FREE) {

*futex = ACQUIRED;

} else {

*futex = CONTENDED;

futex_wait(futex, CONTENDED);

// try again after waking up

lock(futex);

}

}

The futex_wait system call will check to ensure that *futex == val. So, if the *futex gets changed, the function will return immediately rather than sleeping.

Here’s the FUTEX_WAIT section of the Linux futex man page, which hopefully should be clear now.

FUTEX_WAIT (since Linux 2.6.0)

This operation tests that the value at the futex word pointed to by the address uaddr still contains the expected value val, and if so, then sleeps waiting for a FUTEX_WAKE operation on the futex word. The load of the value of the futex word is an atomic memory access (i.e., using atomic machine instructions of the respective architecture). This load, the comparison with the expected value, and starting to sleep are performed atomically and totally ordered with respect to other futex operations on the same futex word. If the thread starts to sleep, it is considered a waiter on this futex word. If the futex value does not match val, then the call fails immediately with the error EAGAIN.

Atomic operations

In order for the lock/unlock implementations to guarantee correctness, we need to rely on what are called atomic operations when reading and modifying the futex across multiple threads. These are operations that the hardware guarantees can be performed atomically, so that there are no possible race conditions.

In my futex model, I assumed the existence of three atomic operations:

- atomic store

- atomic exchange

- atomic compare and exchange

Atomic store isn’t very interesting, it just says that we can atomically set the value of a variable, i.e., that when we do something like this, it happens atomically.

*futex = FREE

In PlusCal, atomic stores are just modeled as assigning a value to a variable, so there’s not much else to sta

Atomic exchange

Atomic exchange looks like this:

oldval = atomic_exchange(x, newval)

You give atomic exchange two arguments: a variable (x) you want to modify, and the new value (newval) you want it to have. The atomic_exchange function will atomically set x=newval and return the value x had before the assignment.

In PlusCal, I modeled it as a macro. Macros can’t return values, so we need to pass in oldval as an argument.

macro atomic_exchange(x, oldval, newval) begin

oldval := x;

x := newval;

end macro;

Then I can invoke it like this in my PlusCal model:

atomic_exchange(mem[a], uprev, Free);

And the resulting behavior is:

uprev := mem[a];

mem[a] := Free;

Atomic compare and exchange

Atomic compare and exchange is sometimes called test-and-set. It looks like this:

oldval = atomic_compare_exchange(x, expecting, newval)

It’s similar to atomic exchange, except that it only performs the exchange if the variable x contains the value expecting. Basically, it’s an atomic version of this:

if (x == expecting)

oldval = atomic_compare_exchange(x, newval)

else

oldval = x

In my PlusCal model, I also implemented it as a macro:

macro atomic_compare_exchange(x, oldval, expecting, newval) begin

oldval := x;

if x = expecting then

x := newval;

end if;

end macro;

Futex modeling basics

Here are the basics constants and variables in my model:

CONSTANTS Processes, Addresses, Free, Acquired, Contended

(*--algorithm futex

variables

mem = [x \in Addresses |-> Free],

a \in Addresses,

...

In addition to modeling Processes, my futex model also models a set of memory address as Addresses. I also defined three constants: Free, Acquired, Contended which have the same role as FREE, ACQUIRED, and CONTENDED in the example C code above.

I model memory as a function (mem) that maps addresses to values, as well as a specific memory address (a). I use a as my futex.

At the top-level, the algorithm should look familiar, it’s basically the same as the mutex.tla one, except that it’s calling acquire_lock and release_lock procedures.

process proc \in Processes

begin

ncs: skip;

acq: call acquire_lock();

cs: skip;

rel: call release_lock();

goto ncs;

end process;

acquire_lock: implementing lock

I based my implementation of the lock on a simplified version of the one in Ulrich Drupper’s Futexes are Tricky paper.

Here’s the model for acquiring the lock. It doesn’t render particularly well in WordPress, so you may want to view the futex.tla file on GitHub directly.

procedure acquire_lock()

variable lprev;

begin

\* Attempt to acquire the lock

Lcmpx1: atomic_compare_exchange(mem[a], lprev, Free, Acquired);

Ltest: while lprev # Free do

\* Mark the lock as contended, assuming it's in the acquired state

Lcmpx2: atomic_compare_exchange(mem[a], lprev, Acquired, Contended);

if lprev # Free then

call_wait: call futex_wait(a, Contended);

end if;

\* Attempt to acquire the lock again

Lcmpx3: atomic_compare_exchange(mem[a], lprev, Free, Contended);

end while;

\* if we reach here, we have the lock

Lret: return;

end procedure;

Note that we need three separate atomic_compare_exchange calls to implement this (each with different arguments!). Yipe!

release_lock: implementing unlock

The unlock implementation is much simpler. We just set the futex to Free and then wake the waiters.

procedure release_lock()

variable uprev;

begin

u_xch: atomic_exchange(mem[a], uprev, Free);

u_wake: if uprev = Contended then

call futex_wake(a);

end if;

u_ret: return;

end procedure;

Modeling the futex_wait/futex_wake calls

Finally, it’s not enough in our model to just invoke futex_wait and futex_wake, we need to model the behavior of these as well! I’ll say a little bit about the relevant kernel data structures in the Linux kernel and how I modeled them

Kernel data structures

The Linux kernel hashes futexes into buckets, and each of these bucket is associated with a futex_hash_bucket structure. For the purposes of our TLA+ model, the fields we care about are:

- queue of threads (tasks) that are waiting on the futex

- lock for protecting the structure

The kernel also uses a structure called a wake-queue (see here for more details) to keep a list of the tasks that have been selected to be woken up. I modeled this list of threads-to-be-woken as a set.

Here are the variables:

variables

...

waitq = [x \in Addresses |-> <<>>], \* a map of addresses to wait queues

qlock = {}, \* traditional mutex lock used by the kernel on the wait queue.

wake = {}; \* processes that have been sent a signal to wake up

I made the following assumptions to simplify my model

- every futex (address) is associated with one queue, rather than hashing and bucketing

- I used a global lock instead of having a per-queue lock

futex_wait

Here’s the basic futex_wait algorithm (links go to Linux source code)

- Take the lock

- Retrieve the current value of the futex.

- Check if the passed value matches the futex value. If not, return.

- Add the thread to the wait queue

- Release the lock

- Wait to be woken up

Note: I assume that calling schedule() inside of the kernel at this point has the effect of putting the thread to sleep, but as I said earlier, I’m not a kernel programmer so I’m not familiar with this code at all.

Here’s my PlusCal model:

procedure futex_wait(addr, val)

begin

wt_acq: await qlock = {};

qlock := {self};

wt_valcheck: if val /= mem[addr] then

qlock := {};

return;

end if;

\* Add the process to the wait queue for this address

wt_enq: waitq[addr] := Append(waitq[addr], self);

qlock := {};

wt_wait: await self \in wake;

wake := wake \ {self};

return;

end procedure;

futex_wake

Here’s what the futex_wake algorithm looks like:

- Take the lock

- Add the tasks to be woken up to the wake queue

- Release the lock

- Wake the tasks on the wake queue

Here’s my PlusCal model of it. I chose to wake only one process in my model, but we could have have woken all of the waiting processes.

procedure futex_wake(addr)

variables nxt = {}

begin

wk_acq: await qlock = {};

qlock := {self};

wk_deq: if waitq[addr] /= <<>> then

nxt := {Head(waitq[addr])};

waitq[addr] := Tail(waitq[addr]);

end if;

wk_rel: qlock := {};

wk_wake: wake := wake \union nxt;

return;

end procedure;

You can see the full model on GitHub at futex.tla.

Checking for properties

One of the reasons to model in TLA+ is to check properties of the specification. I care about three things with this specification:

- It implements mutual exclusion

- It doesn’t make system calls when there’s no contention

- Processes can’t get stuck waiting on the queue forever

Mutual exclusion

We check mutual exclusion the same way we did in our mutex.tla specification, by asserting that there are never two different processes in the critical section at the same time. This is our invariant.

MutualExclusion == \A p1,p2 \in Processes : pc[p1]="cs" /\ pc[p2]="cs" => p1=p2

No contention means no system calls

The whole point of using futexes to implement locks was to avoid system calls in the cases where there’s no contention. Even if our algorithm satisfies mutual exclusion, that doesn’t mean that it avoids these system calls.

I wrote an invariant for the futex_wait system call, that asserts that we only make the system call when there’s contention. I called the invariant OnlyWaitUnderContention, and here’s how I defined it. I created several helper definitions as well.

LockIsHeld == mem[a] /= Free

ProcessAttemptingToAcquireLock(p) == pc[p] \in {"Lcmpx1", "Ltest", "Lcmpx2", "call_wait", "Lcmpx3", "wt_acq", "wt_valcheck", "wt_enq", "wt_wait"}

Contention == LockIsHeld /\ \E p \in Processes : ProcessAttemptingToAcquireLock(p)

OnlyWaitUnderContention == \E p \in Processes : pc[p]="call_wait" => Contention

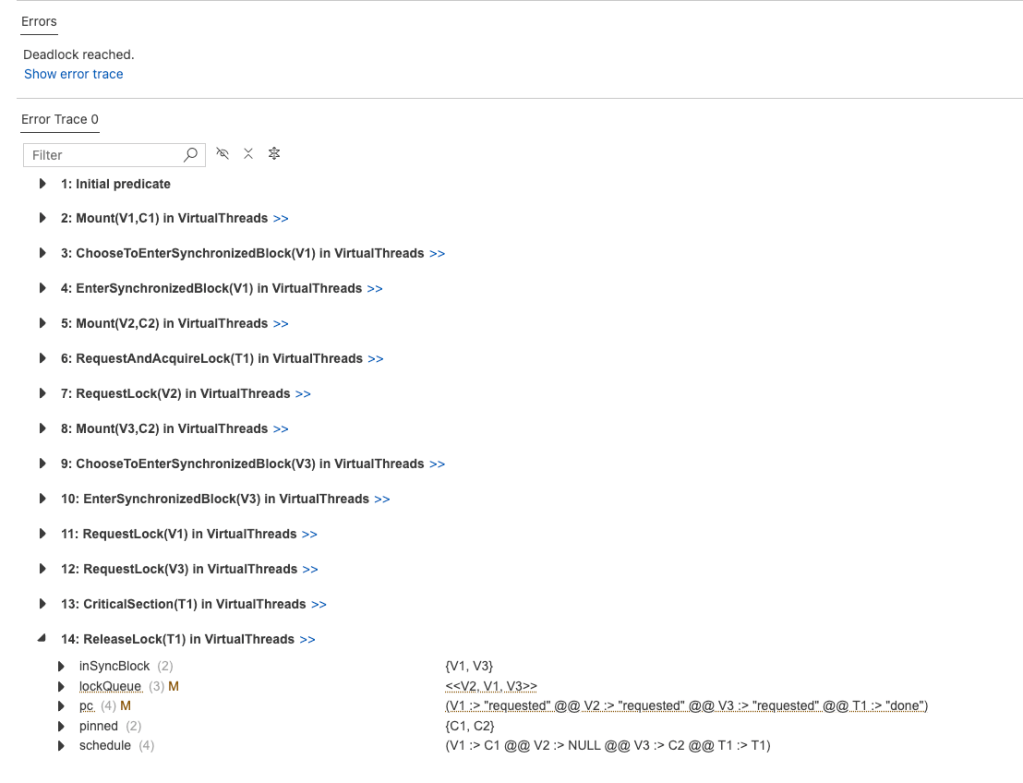

Nobody gets stuck waiting

Recall earlier in the blog post how we had to modify the prototype of the futex_wait system call to take an additional argument, in order to prevent a race condition that could leave a process waiting forever on the queue.

We want to make sure that we have actually addressed that risk. Note that the comments in the Linux source code specifically call out this risk.

I checked this by defining an invariant that stated that it never can happen that a process is waiting and all of the other processes are past the point where they could wake up the waiter.

Stuck(x) == /\ pc[x] = "wt_wait"

/\ x \notin wake

/\ \A p \in Processes \ {x} : \/ pc[p] \in {"ncs", "u_ret"}

\/ /\ pc[p] \in {"wk_rel", "wk_wake"}

/\ x \notin nxt[p]

NoneStuck == ~ \E x \in Processes : Stuck(x)

Final check: refinement

In addition to checking mutual exclusion, we can check that our futex-based lock model (futex.tla) implements our original high-level mutex model (mutex.tla) by means of a refinement mapping.

To do that, we need to define mappings between the futex model variables and the mutex model variables. The mutex model has two variables:

- lock – the model of the lock

- pc – the program counters for the processes

I called my mappings lockBar and pcBar. Here’s what the mapping looks like:

InAcquireLock(p) == pc[p] \in {"Lcmpx1", "Ltest", "Lcmpx2", "call_wait", "Lcmpx3", "Lret"}

InFutexWait(p) == pc[p] \in {"wt_acq", "wt_valcheck", "wt_enq", "wt_wait"}

InReleaseLockBeforeRelease(p) == pc[p] \in {"u_xch"}

InReleaseLockAfterRelease(p) == pc[p] \in {"u_wake", "u_ret"}

InFutexWake(p) == pc[p] \in {"wk_acq", "wk_deq", "wk_rel", "wk_wake"}

lockBar == {p \in Processes: \/ pc[p] \in {"cs", "rel"}

\/ InReleaseLockBeforeRelease(p)}

pcBar == [p \in Processes |->

CASE pc[p] = "ncs" -> "ncs"

[] pc[p] = "cs" -> "cs"

[] pc[p] = "acq" -> "acq"

[] InAcquireLock(p) -> "acq"

[] InFutexWait(p) -> "acq"

[] pc[p] = "rel" -> "rel"

[] InReleaseLockBeforeRelease(p) -> "rel"

[] InReleaseLockAfterRelease(p) -> "ncs"

[] InFutexWake(p) -> "ncs"

]

mutex == INSTANCE mutex WITH lock <- lockBar, pc <- pcBar

We can then define a property that says that our futex specification implements the mutex specification:

ImplementsMutex == mutex!Spec

Finally, in our futex.cfg file, we can specify that we want to check the invariants, as well as this behavioral property. The relevant config lines look like this:

INVARIANT

MutualExclusion

OnlyWaitUnderContention

NoneStuck

PROPERTY

ImplementsMutex

You can find my repo with these models at https://github.com/lorin/futex-tla.