The Human Factor by William Langewiesche is an account of how Air France Flight 447 crashed back in 2009. It’s a great piece of long-form journalism.

[Recently deceased engineer Earl] Wiener pointed out that the effect of automation is to reduce the cockpit workload when the workload is low and to increase it when the workload is high.

That’s basically Nassim Nicholas Taleb’s definition of fragility: where the potential downside is much greater than the potential upside.

But this is what really struck me:

[U. Michigan Industrial & Systems Engineering Professor Nadine] Sarter said, “… Complexity means you have a large number of subcomponents and they interact in sometimes unexpected ways. Pilots don’t know, because they haven’t experienced the fringe conditions that are built into the system. I was once in a room with five engineers who had been involved in building a particular airplane, and I started asking, ‘Well, how does this or that work?’ And they could not agree on the answers. So I was thinking, If these five engineers cannot agree, the poor pilot, if he ever encounters that particular situation … well, good luck.””

We also build software by connecting together different subcomponents. We know that the hardware underlying these subcomponents can fail, and in order to provide reliability for our customers we must be able to deal with these failures. If we’re sophisticated, we turn to automation: we try to build fault-tolerant systems that can automatically detect failures and compensate for them.

But the behavior of these types of systems is difficult to reason about, precisely because they take action automatically based on self-monitoring. These systems can handle hard failures of individual components: when something has obviously failed. But if it’s a soft failure, where the component is still partially working, or if two independent components fail simultaneously, then the system may not be able to handle it. Adding automation to handle failures introduces new failure modes even as it eliminates old ones, and the new ones may be much harder for an operator to understand.

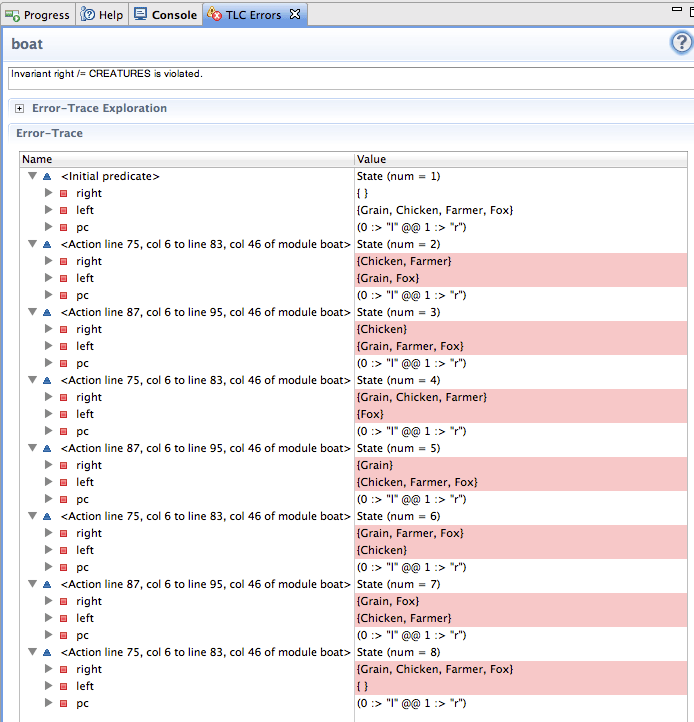

Consider the AWS outage of October 2012, which took down multiple websites that deploy on Amazon’s cloud. The outage was a result of:

1. A hardware failure on a data collection server

2. A DNS update not propagating to all internal DNS servers

3. A memory leak bug in an agent that monitors the health of EBS (storage) servers

The agents collect operational data from the storage servers and transfer it to data collection servers. Some agents couldn’t reach the collection servers because of a stale DNS entry. Because the agents also had a memory leak bug, they consumed too much memory on the storage servers.

Lack of sufficient memory is a good way to create a soft failure: the component still works, but in a degraded fashion. These memory-poor servers couldn’t keep up with requests, and eventually became stuck. The system detected the stuck servers (a hard failure), and failed over to healthy servers, but there were so many stuck servers that the healthy servers couldn’t keep up, and also became stuck.

The irony is that this failure is entirely due to the monitoring subsystem, which is intended to increase system reliability! It happened because of the co-incidence of a hardware failure in one component of the monitoring subsystem (a data collection server) and a software bug in another component of the monitoring subsystem (data collection agent).

We can’t avoid automation. In the case of the airlines, the automation has significantly increased safety, even though it increases the chances of incidents like Air France 447. For cloud software, this type of fault-tolerance automation does result in more reliable systems.

But, while these systems mean failure is less likely, when it does happen, it’s much more difficult to understand what’s happening. The future of cloud software is systems that fail much less often, but much harder. Buckle up.