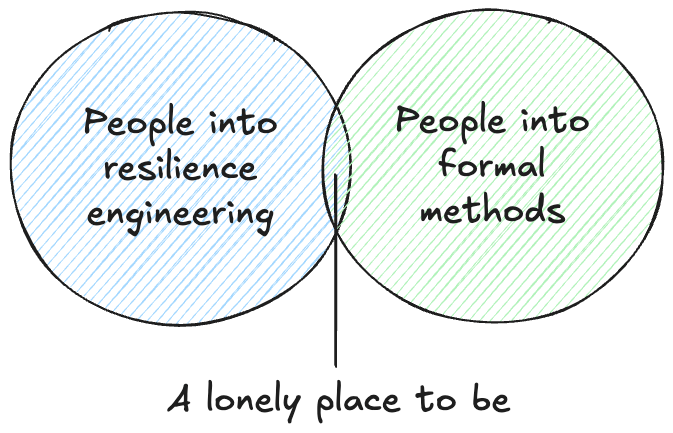

If you’re a regular reader of this blog, you’ll have noticed that I tend to write about two topics in particular:

- Resilience engineering

- Formal methods

I haven’t found many people who share both of these interests.

At one level, this isn’t surprising. Formal methods people tend to have an analytic outlook, and resilience engineering people tend to have a synthetic outlook. You can see the clear distinction between these two perspectives in the transcript of Leslie Lamport’s talk entitled The Future of Computing: Logic or Biology. Lamport is clearly on the side of the logic, so much so that he ridicules the very idea of taking a biological perspective on software systems. By contrast, resilience engineering types actively look to biology for inspiration on understanding resilience in complex adaptive systems. A great example of this is the late Richard Cook’s talk on The Resilience of Bone.

And yet, the two fields both have something in common: they both recognize the value of creating explicit models of aspects of systems that are not typically modeled.

You use formal methods to build a model of some aspect of your software system, in order to help you reason about its behavior. A formal model of a software system is a partial one, typically only a very small part of the system. That’s because it takes effort to build and validate these models: the larger the model, the more effort it takes. We typically focus our models on a part of the system that humans aren’t particularly good at reasoning about unaided, such as concurrent or distributed algorithms.

The act of creating and explicit model and observing its behavior with a model checker gives you a new perspective on the system being modeled, because the explicit modeling forces you to think about aspects that you likely wouldn’t have considered. You won’t say “I never imagined X could happen” when building this type of formal model, because it forces you to explicitly think about what would happen in situations that you can gloss over when writing a program in a traditional programming language. While the scope of a formal model is small, you have to exhaustively specify the thing within the scope you’ve defined: there’s no place to hide.

Resilience engineering is also concerned with explicit models, in two different ways. In one way, resilience engineering stresses the inherent limits of models for reasoning about complex systems (c.f., itsonlyamodel.com). Every model is incomplete in potentially dangerous ways, and every incident can be seen through the lens of model error: some model that we had about the behavior of the system turned out to be incorrect in a dangerous way.

But beyond the limits of models, what I find fascinating about resilience engineering is the emphasis on explicitly modeling aspects of the system that are frequently ignored by traditional analytic perspectives. Two kinds of models that come up frequently in resilience engineering are mental models and models of work.

A resilience engineering perspective on an incident will look to make explicit aspects of the practitioners’ mental models, both in the events that led up to that incident, and in the response to the incident. When we ask “How did the decision make sense at the time?“, we’re trying to build a deeper understanding of someone else’s state of mind. We’re explicitly trying to build a descriptive model of how people made decisions, based on what information they had access to, their beliefs about the world, and the constraints that they were under. This is a meta sort of model, a model of a mental model, because we’re trying to reason about how somebody else reasoned about events that occurred in the past.

A resilience engineering perspective on incidents will also try to build an explicit model of how work happens in an organization. You’ll often heard the short-hand phrase work-as-imagined vs work-as-done to get at this modeling, where it’s the work-as-done that is the model that we’re after. The resilience engineering perspective asserts that the documented processes of how work is supposed to happen is not an accurate model of how work actually happens, and that the deviation between the two is generally successful, which is why it persists. From resilience engineering types, you’ll hear questions in incident reviews that try to elicit some more details about how the work really happens.

Like in formal methods, resilience engineering models only get at a small part of the overall system. There’s no way we can build complete models of people’s mental models, or generate complete descriptions of how they do their work. But that’s ok. Because, like the models in formal methods, the goal is not completeness, but insight. Whether we’re building a formal model of a software system, or participating in a post-incident review meeting, we’re trying to get the maximum amount of insight for the modeling effort that we put in.

2 thoughts on “Models, models every where, so let’s have a think”