There are two approaches to doing post-incident analysis:

- the (traditional) root cause analysis (RCA) perspective

- the (more recent) learning from incidents (LFI) perspective

In the RCA perspective, the occurrence of an incident has demonstrated that there is a vulnerability that caused the incident to happen, and the goal of the analysis is to identify and eliminate the vulnerability.

In the LFI perspective, an incident presents the organization with an opportunity to learn about the system. The goal is to learn as much as possible with the time that the organization is willing to devote to post-incident work.

The RCA approach has the advantage of being intuitively appealing. The LFI approach, by contrast, has three strikes against it:

- LFI requires more time and effort than RCA

- LFI requires more skill than RCA

- It’s not obvious what advantages LFI provides over RCA.

I think the value of LFI approach is based on assumptions that people don’t really think about because these assumptions are not articulated explicitly.

In this post, I’m going to highlight two of them.

Nobody knows how the system really works

The LFI approach makes the following assumption: No individual in the organization will ever have an accurate mental model about how the entire system works. To put it simply:

- It’s the stuff we don’t know that bites us

- There’s always stuff we don’t know

By “system” here, I mean the socio-technical system, which includes both the software and what it does, and the humans who do the work to develop and operate the system.

You’ll see the topic of incorrect mental models discussed in the safety literature in various ways. For example, David Woods uses the term miscalibration to describe incorrect mental models, and Diane Vaughan writes about structural secrecy, which is a mechanism that leads to incorrect mental models.

But incorrect mental models are not something we talk much about explicitly in the software world. The RCA approach implicitly assumes there’s only a single thing that we didn’t know: the root cause of the incident. Once we find that, we’re done.

To believe that the LFI approach is worth doing, you need to believe that there is a whole bunch of things about the system that people don’t know, not just a single vulnerability. And there are some things that, say, Alice knows that Bob doesn’t, and that Alice doesn’t know that Bob doesn’t know.

Better system understanding leads to better decision making in the future

The payoff for RCA is clear: the elimination of a known vulnerability. But the payoff for LFI is a lot fuzzier: if the people in the organization know more about the system, they are going to make better decisions in the future.

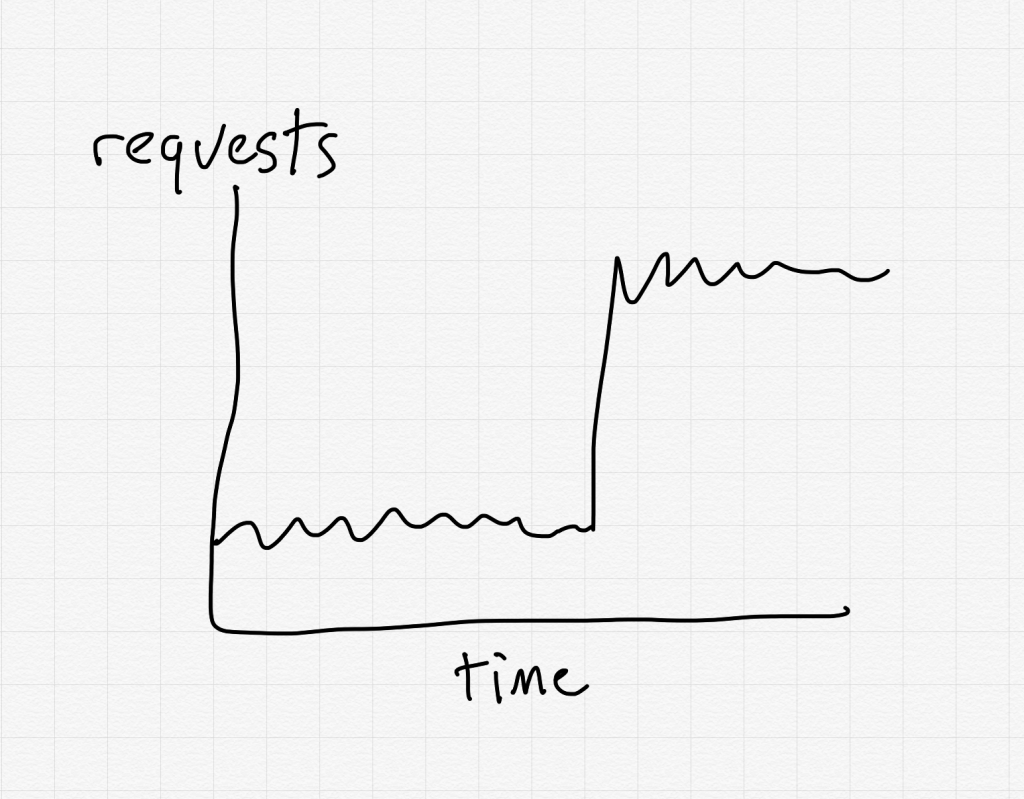

The problem with articulating the value is that we don’t know when these future decisions will be made. For example, the decision might happen when responding to the next incident (e.g., now I know how to use that observability tool because I learned from how someone else used it effectively in the last incident). Or the decision might happen during the design phase of a future software project (e.g., I know to shard my services by request type because I’ve seen what can go wrong when “light” and “heavy” requests are serviced by same cluster) or during the coding phase (e.g., I know to explicitly set a reasonable timeout because Java’s default timeout is way too high).

The LFI approach assumes that understanding the system better will advance the expertise of the engineers in the organization, and that better expertise means better decision making.

On the one hand, organizations recognize that expertise leads to better decision making: it’s why they are willing to hire senior engineers even though junior engineers are cheaper. On the other hand, hiring seems to be the only context where this is explicitly recognized. “This activity will advance the expertise of our staff, and hence will lead to better future outcomes, so it’s worth investing in” is the kind of mentality that is required to justify work like the LFI approach.