This post is mostly an excerpt from the book Designing Engineers by Louis Bucciarelli. This book describes Bucciarelli’s observational study of engineers doing design work at three different engineering companies.

At some point, I’ll write a proper review of the book, but I wanted to highlight a specific passage, a meeting among engineers working to solve a specific problem.

The engineers attending this meeting work at a company that sells photograph processing machines. The company is planning on releasing a new product (“Atlas”) in a few months, but there’s a problem with the design: a phenomenon that they call dropout. Dropout happens when parts of the image that are barely visible end up not getting printed on the paper. The problem can be hard to notice unless someone looks very closely at the photo, but it’s enough of an issue that they are putting in resources to solving it.

This meeting is being led by Sergio, the engineer leading the effort to solve the dropout problem. Before this meeting, he identified fourteen potential solutions to the dropout problems. He’s called this engineering meeting in order to apply a structured decision-making process (the Pugh Method) to help him narrow down this list to the most promising-sounding solutions.

The meeting does not go as the organizer hoped. The transcript is long-ish, but worth reading in full. You might even find it familiar.

Sergio: OK. Let’s start. You all got this. [He holds up a description of Pugh methodology]. I sent it around last Thursday. It pretty much says what we’re going to try to do, except I’m going to make a few changes. You’ll see as we go along. The basic idea today is that we want to first set up some criteria to judge. Then we compare how the fourteen go, compare them against these criteria. By the end of this morning I’d like to have narrowed things down, not to one option, but to three, say, something we can get going on. Yeah, Harold.

Harold: It says in this method that we ought to pick a baseline option to compare against. How are we going to do that? It seems to me any one of the fourteen would be as good or bad, for that matter, as any of the others.

Sergio: I thought about that, and here is what I propose. Let’s pick the option we know best, OK? Say the QWP. We know how that works, and other than that it probably won’t fit in the space we have to play with, it still can be our reference. But first we have to set up some criteria. So, let me get this chart around here.

Hans: Obviously we need a criterion, something like “Gets the job done” or “Eliminates dropout.”

Sergio: Yeah, that’s got to be one. The thing has got to work, to solve the problem. How did you state it?

Marco: What do we mean when we go and claim that, say, the QWEP eliminates the dropout? I mean, all of those up there have a chance of doing the job.

Sergio: I know. But we score, not with numbers but say three, four marks—better than the baseline, say the QWP. This is where the baseline comes in. Second would be neutral—no better, no worse than the QWP—and third would be negative; that is, we think it won’t be as good as what we know works now.

Marco: Yeah, but some of these options I think might work as good, even better on some papers but probably won’t work at all on others. How do you grade it then?

Sergio: What do you mean? Give me a more specific example.

Marco: I mean like with the air knife. It might work with Z-weight paper, but with the heavier M-weight I don’t think it will work.

Hans: Why not make that another criterion: “Works with all papers.“

Sergio: Or “Sensitivity to paper.” Sort of pull that out from under “Does the job.”

Marco: You mean that there are some options that will do the job, but some of those won’t be able to handle the heavy paper?

Sergio: Yeah, that’s one way to look at it. “Does the job” is our best guess that the thing will work, but we give paper type a separate category. We may want to say something else has to be done to handle the heavy paper; that becomes another problem.

Fritz: How do we know whether paper type is critical for the air knife? It seems to me we don’t really know what the problem is. How can we compare options when we don’t know what is causing the problem?

Marco: Fritz, that’s a good point. Do we really know enough to—

Sergio: We know we have dropout on Atlas. We know that the QWP gives good results. We have a pretty good idea of what consistency it takes to give good print—print that a trained eye can’t find a hole in. (With a magnifying glass, you still see some.)

Fritz: Yes, but we can know, and should know, a lot more before we go judging these proposals on whether or not they will solve the problem. If this place hadn’t cut back on its chemistry research, we might have a chance of knowing what the hell is going on, not just with Atlas but we had it on Mars as well.

Sergio: Look, some things are beyond our control. We have no power over the powers-that-be. We don’t have a chemistry group working on this problem to call up and say “Get over here and help us evaluate these options.” We’ve got to go with what we have. Atlas is due to go out onto the streets in seven months.

Fritz: That’s the way it always goes around her. Someone wants your solutions yesterday.

Sergio: OK. So we have “Eliminates dropout” and “Sensitivity to paper.” What are some others?

Hans: Cost.

Marco: Have you guys thought about some kind of chemical pretreatment… different papers?

Sergio: Cost. Let’s think about that. Is cost really that important? Leonard says he doesn’t see cost as really significant unless it really is some huge sum. But I don’t see how we will ever get to that point. And Atlas—

Harold: Yeah, I don’t see how unit cost can be that great. We’re not going to be able to fool around much inside Atlas at this late date.

Marco: We ought to think about what we can do without going inside.

Hans: On the other hand, if we do convince them that they have to move the paper feed, say, it is going to get costly.

Harold: In terms of engineering change but not in terms of unit costs. We still aren’t going to go in there with some exotic machinery. All those options, except maybe the E&M device, are just bending metal, cams, gears… mechanical stuff, nothing fancy.

George: We might have a problem holding tolerances. Machining can get expensive. We ask too much of my people, even with the mechanical parts.

Sergio: Maybe we make that another category, another criterion: “Engineering change,” “Extent of engineering change.”

Harold: What you really want to say is something like “Compatible with existing product.” Like the QWP we know will work fine. It does in Mars, but we know it will be extremely hard to fit in Atlas, so… Or the E&M that’s going to require a power supply, right?

Fritz: But the QWP is our reference. That’s not a good example. And that’s not a good example. And, for that matter, what good is the criterion if we know the QWP won’t fit? If that’s the case, won’t all the options be scored a plus, all the same?

Sergio: Good point, good point. But I see some that will be just as hard to retrofit—for example, the cam with a solenoid. Solenoids aren’t any miniature electronic device. They’ve got to have room, especially with the forces and reaction times we’re going to be demanding.

Hans: And the air knife requires a plenum, or the E&M—Marco, was it you who said they will need a power supply?

Sergio: Fritz, you have a good point, but let’s put it up there for now. There won’t be maybe any negatives there, but still… OK? How did you say it?

Harold: “Compatible with existing product” or maybe we ought to say “products,” with Leonard in mind.

Sergio: Yeah, got it.

Fritz: That brings up another thing. Who are we making this design for? Leonard out in Colorado and Atlas are not in sync. Atlas is well along, they’re getting into the panic mode now. But Leonard has more time, another year at least, right?

Sergio: I spoke to Leonard yesterday, and even though he has another year past Atlas, he wants to se a solution to what he thinks is his dropout problem well before that. He doesn’t want to go the panic route.

Fritz: But we still have more time with him. And shouldn’t we be thinking about the long term?

Sergio: We can’t afford to do too much of that. I’ve got the higher-ups breathing down my neck to get something going here. That makes me think fo another criterion: How well can we meet a schedule? Let’s say “Ease of schedule.”

George: How about “Pain and suffering”? [Laughter]

Sergio: No, we want to be positive about this.

Marco: Yeah, so we can mark them down. [Laughter]

Fritz: That’s why we chose the QWP as a baseline. He knows that can’t possibly fit here.

Sergio: Come on guys. That’s not true. Let’s get serious. We want to get out of here by lunchtime. Jeez, is it already 10:30?

Hans: I’ve got 10:40.

Sergio: OK. So far we’ve got—

Harold: I think we’re missing a big one. You all know how difficult it is to keep the QWP clean. Anything mechanical you add in there is going to collect sludge. Some of those, like the cam, are going to have. areal problem there with that—keeping clean.

Sergio: Good. That’s another good one. The guys in Service are not going to like it if they get called out every week.

Marco: Does that figure into the cost, the cost of servicing? Do we need a separate category?

Sergio: I think we ought to break that one out, just like we did with the paper. That’s something we are liable not to think of—what it takes to maintain the fix in the field. So let’s add—

Fritz: We don’t even know if it will work.

Sergio: We got some interesting results yesterday with a mock-up. I think it looks promising.

Fritz: But still, it’s got a long way to go. That’s what I mean. We don’t really know. if it will work, and I, at least, can’t make a good judgment even though you may be able to, because I don’t think we understand enough about the problem!

Marco: I’m with Fritz on that. I don’t think. we have enough information about these different options. I’m finding it hard to do. this method, and I think the reason is because we don’t really understand the problem.

Sergio: How much do we need to know? I admit that the E&M is a long shot, that we’ve got to get it going, that it will take a longer time to evaluate than, say, the cam concepts, and we’ve been promised a machine for next week. When we get the hardware, we can do both, evaluate the E&Ms and, in the process, get a firmer grip on what is the problem. But we don’t have all year. Jeez, it’s 11:00. We don’t have all morning either. And besides, this is just an exercise; we are not going to pick a definite option. and go with that. We only want to narrow the field some this morning. Then we give it a hard look again, after we’ve done some work on the three, come back at it and evaluate again. In fact, I can see us running pretty far with, say, two or three options in parallel, as long as they don’t interfere. Maybe that’s another thing to consider.

Hans: Seeing what time it is, maybe we better cut off our criteria here. Serge, I think we better get to ranking.

Sergio: OK, OK. So far we’ve got ‘Does the job,” “Sensitive to paper,” “Cost,” “Compatible with existing hardware,” “Ease of schedule,” “Ease of maintenance.” Anyone think of any more?

George: How about “Ease of production?”

Marco: That’s in cost. I see that as a main factor in cost.

Fritz: Look, I think we have a problem with these criteria. I’m having a hell of a time keeping them straight, trying to fix what they might mean. Are they all to be considered as having the same priority? I still think this exercise is not useful unless we know more about what we have to do, what the problem is.

Marco: I think even then these criteria would get all mixed up. When we say “Do the job” I see costs, sludge all in that, too.

Sergio: We are always going to have that problem. Where we are now, we’ve got to move. All I want is to get us narrowed down.

Fritz: But you yourself think PT’s additional option is worth keeping. I don’t think we’re ready.

Sergio: It’s getting late. We’re not going. to get there today. That’s clear. I’ll tell you what. Can we meet again? [Grunts, groans]

Sergio: No, I promise you. In the meantime, Hans and I will go back and sort out these criteria, try to explain what we see as what they are meant to measure. At least in that way we will start on the same wavelength. I will send you that before we get together. Then we will narrow.

Marco: When? I’ve got to go out to Colorado next week for two days. Can you take that into account?

Fritz: And I’m tied up in the lab the early part of the week.

George: We’ve got a production trial scheduled sometime.

Sergio: Look, I’ll have Cheryl survey, but it might have to go another week. I’ve got to get out and back to Colorado myself sometime next week. OK? Is that it? That’s enough!

(pp. 152–156)

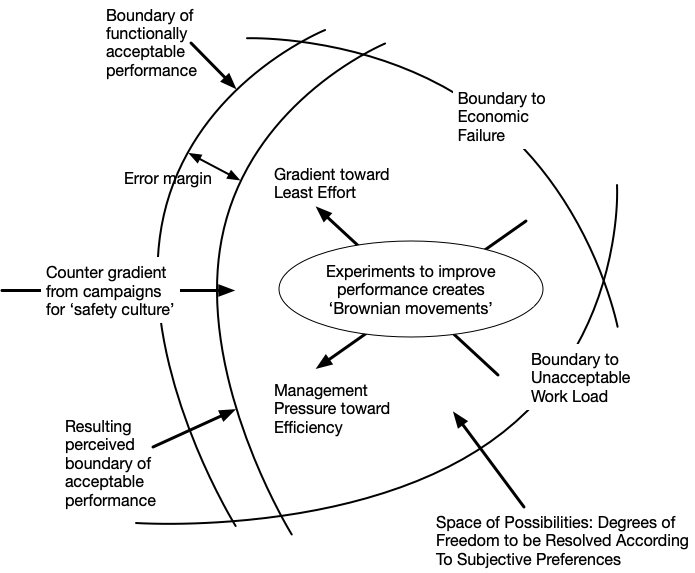

The Pugh technique is an appealing model in principle, but we see problems crop up as Sergio tries to apply it: the engineers work to define criteria, but the categories are slippy. They have different opinions about how to cut up the space into categories, and whether they have enough information to even evaluate these criteria.

Note how well defined the problem seems to be on first glance. It’s a specific problem (dropout) on a system that otherwise has been fully designed. Not only that, but potential solutions have already been identified! Sergio’s goal is just to narrow down the solution space so that they can explore three options instead of fourteen.

Instead of a structured process, we see a much messier interaction, one that ultimately frustrates Sergio, who used the phrase “the disaster meeting” to describe what happened. What we observe, though, is a kind of progress: a group of engineers who have different understandings of the situations trying to establish common ground, building a shared understanding so that they can work together to accomplish this task. Real engineering work is messy.