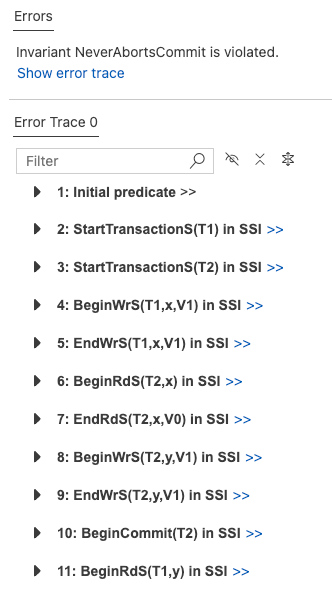

Amazon’s recent announcement of their spec-driven AI tool, Kiro, inspired me to write a blog post on a completely unrelated topic: formal specifications. In particular, I wanted to write about how a formal specification is different from a traditional program. It took a while for this idea to really click in my own head, and I wanted to motivate some intuition here.

In particular, there have been a number of formal specification tools that have been developed in recent years which use programming-language-like notation, such as FizzBee, P, PlusCal, and Quint. I think these notations are more approachable for programmers than the more set-theoretic notation of TLA+. But I think the existence of programming-language-like formal specification languages makes it even more important to drive home the difference between a program and a formal spec.

The summary of this post is: a program is a list of instructions, a formal specification is a set of behaviors. But that’s not very informative on its own. Let’s get into it.

What kind of software do we want to specify

Generally speaking, we can divide the world of software into two types of programs. There is one type where you give the program a single input, and it produces a single output, and then it stops. The other type is one that runs for an extended period of time and interacts with the world by receiving inputs over time, and generating outputs over time. In a paper published in the mid 1980s, the computer scientists David Harel (developer of statecharts) and Amir Pneuli (the first person to apply temporal logic to software specifications) made a distinction between programs they called transformational (which is like the first kind) and the another which they called reactive.

A compiler is an example of a transformational tool, but you can think of many command-line tools as falling into this category. An example of the second type is the flight control software in an airplane, which runs continuously, taking in inputs and generating outputs over time. In my world, we call services are a great example of reactive systems. They’re long-running programs that receive requests as inputs and generate responses as outputs. The specifications that I’m talking about here apply to the more general reactive case.

A motivating example: a counter

Let’s consider the humble counter as an example of a system whose behavior we want to specify. I’ll describe what operations I want my counter to support using Python syntax:

class Counter:

def inc() -> None:

...

def get() -> int:

...

def reset() -> None:

...

My example will be sequential to keep things simple, but all of the concepts apply to specifying concurrent and distributed systems as well. Note that implementing a distributed counter is a common system design interview problem.

Behaviors

Above I just showed the method signatures, but I implemented this counter and interacted with it in the Python REPL, here’s what that looked like:

>>> c = Counter()

>>> c.inc()

>>> c.inc()

>>> c.inc()

>>> c.get()

3

>>> c.reset()

>>> c.inc()

>>> c.get()

1

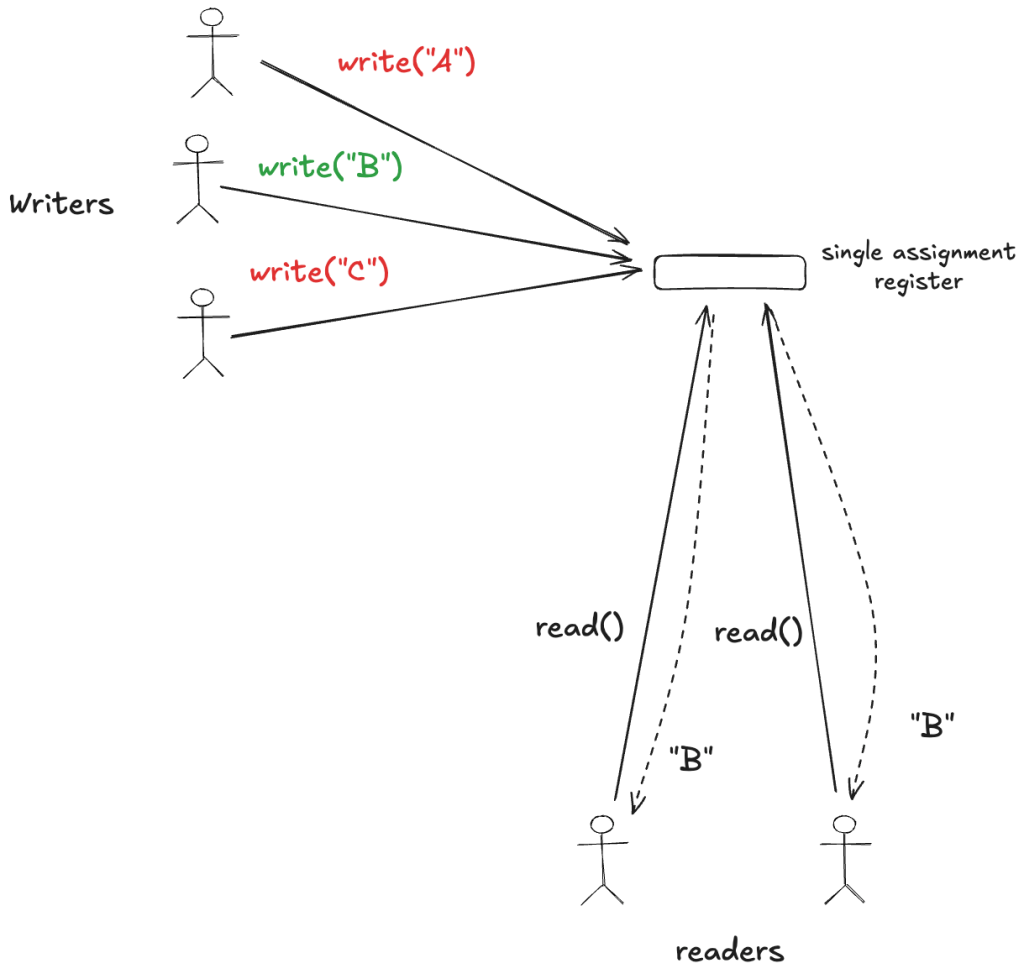

People sometimes refer to the sort of thing above by various names: a session, an execution, an execution history, an execution trace. The formal methods people refer to this sort of thing as a behavior, and that’s the term that we’ll use in the rest of this post. Specifications are all about behaviors.

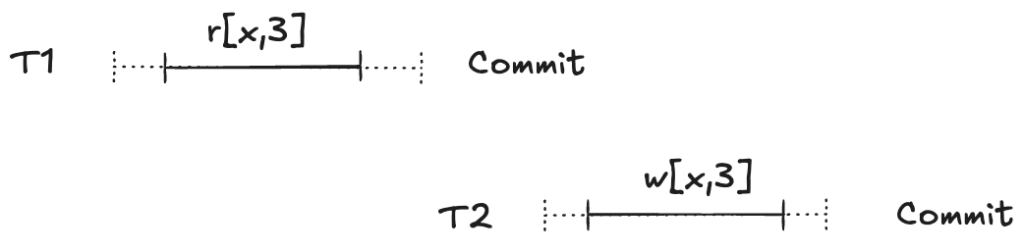

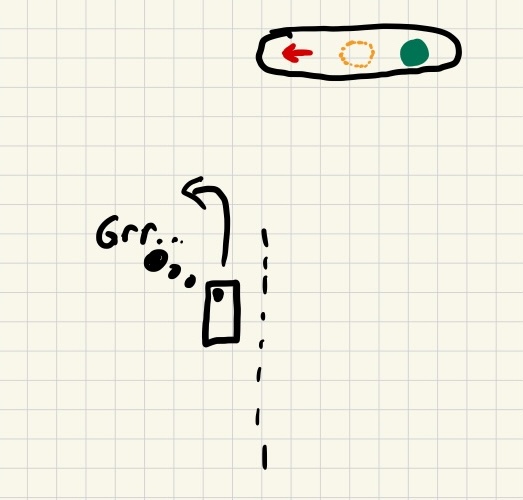

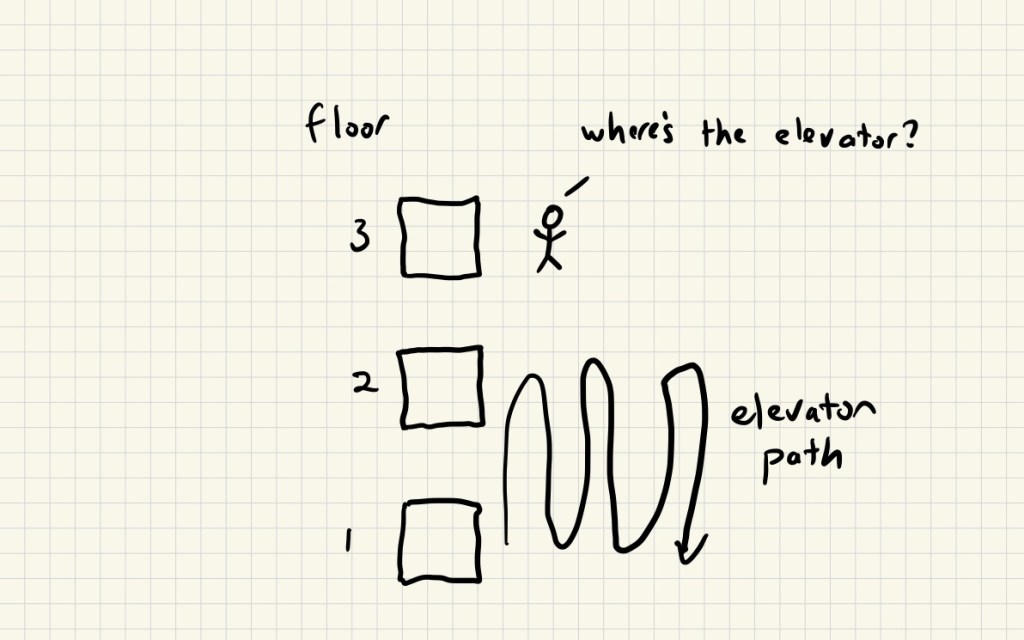

Sometimes I’m going to draw behaviors in this post. I’m going to denote a behavior as a squiggle.

To tie this back to the discussion about reactive systems, you can think of method invocation as inputs, and return values as outputs. The above example is a correct behavior for our counter. But a behavior doesn’t have to be correct: a behavior is just an arbitrary sequence of inputs and outputs. Here’s an example of an incorrect behavior for our counter.

>>> c = Counter()

>>> c.inc()

>>> c.get()

4

We expected the get method to return 1, but instead it returned 4. If we saw that behavior, we’d say “there’s a bug somewhere!”

Specifications and behaviors

What we want out of a formal specification is a device that can answer the question: “here’s a behavior: is it correct or not?”. That’s what a formal spec is for a reactive system. A formal specification is an entity such that, given a behavior, we can determine whether the behavior satisfies the spec. Correct = satisfies the specification.

Once again, a spec is a thing that will tell us whether or not a given behavior is correct.

A spec as a set of behaviors

I depicted a spec in the diagram above as, literally, a black box. Let’s open that box. We can think of a specification simply as a set that contains all of the correct behaviors. Now, the “correct?” processor above is just a set membership check: all it does it check if behavior is an element of the set spec.

What could be simpler?

Note that this isn’t a simplification: this is what a formal specification is in a system like TLA+. It’s just a set of behaviors: nothing more, nothing less.

Describing a set of behaviors

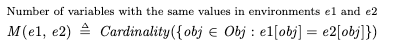

You’re undoubtedly familiar with sets. For example, here’s a set of the first three positive natural numbers: . Here, we described the set by explicitly enumerating each of the elements.

While the idea of a spec being a set of behaviors is simple, actually describing that set is trickier. That’s because we can’t explicitly enumerate the elements of the set like we did above. For one thing, each behavior is, in general, of infinite length. Taking the example of our counter, one valid behavior is to just keep calling any operation over and over again, ad infinitum.

>>> c = Counter()

>>> c.get()

0

>>> c.get()

0

>>> c.get()

0

... (forever)

A behavior of infinite length

This is a correct behavior for our counter, but we can’t write it out explicitly, because it goes on forever.

The other problem is that the specs that we care about typically contain an infinite number of behaviors. If we take the case of a counter, for any finite correct behavior, we can always generate a new correct behavior by adding another inc, get, or reset call.

So, even if we restricted ourselves to behaviors of finite length, if we don’t restrict the total length of a behavior (i.e., if our behaviors are finite but unbounded, like natural numbers), then we cannot define a spec by explicitly enumerating all of the behaviors in the specification.

And this is where formal specification languages come in: they allow us to define infinite sets of behaviors without having to explicitly enumerate every correct behavior.

Describing infinite sets by generating them

Mathematicians deal with infinite sets all of the time. For example, we can use set-builder notation to describe the infinitely large set of all even natural numbers without explicitly enumerating each one:

The example above references another infinite set, the set of natural numbers (ℕ). How do we generate that infinite set without reference to another one?

One way is to define the set by describing how to generate the set of natural numbers. To do this, we specify:

- an initial natural number (either 0 or 1, depending on who you ask)

- a successor function for how to generate a new natural number from an existing one

This allows us to describe the set of natural numbers without having to enumerate each one explicitly. Instead, we describe how to generate them. If you remember your proofs by induction from back in math class, this is like defining a set by induction.

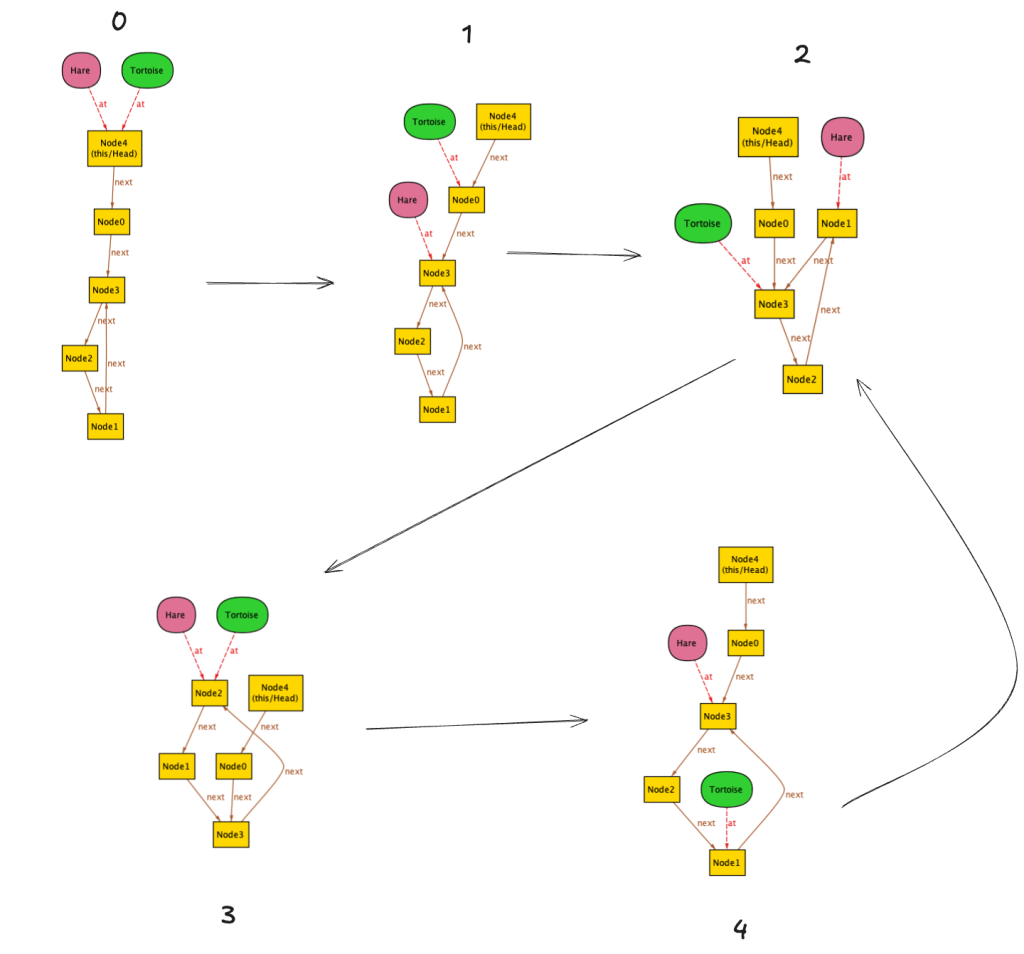

Specifications as generating a set of behaviors

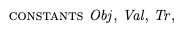

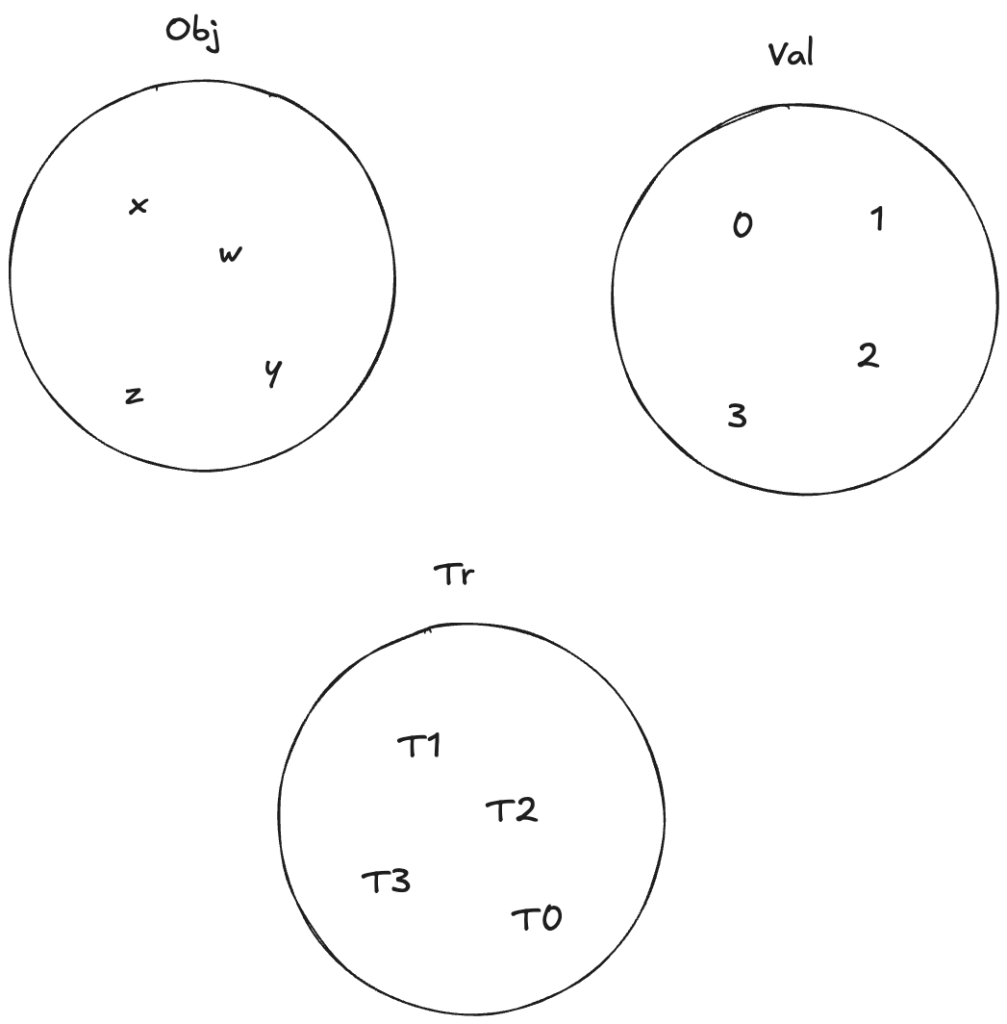

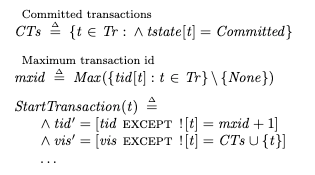

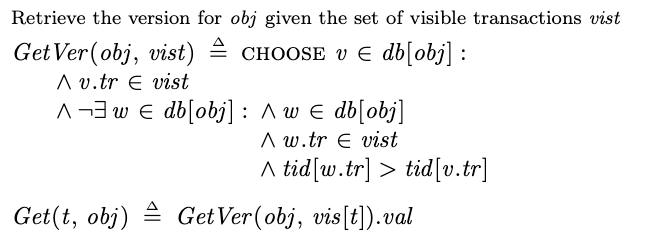

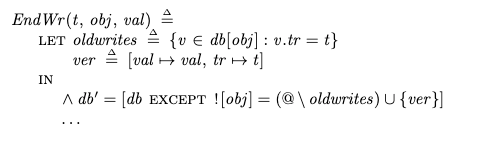

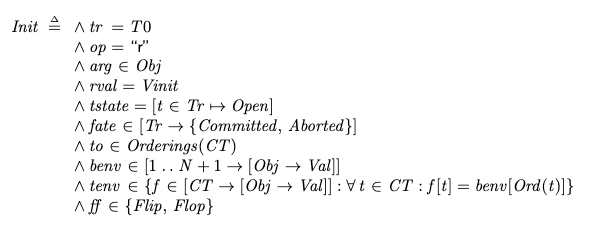

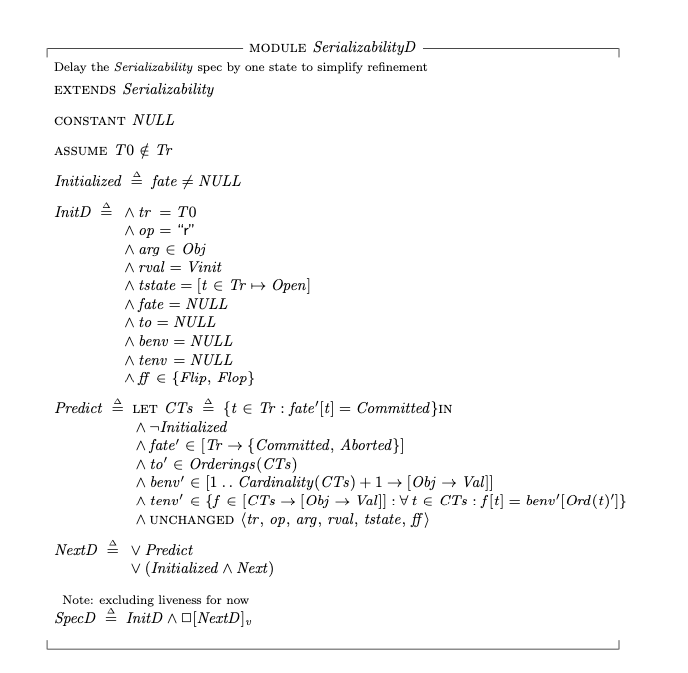

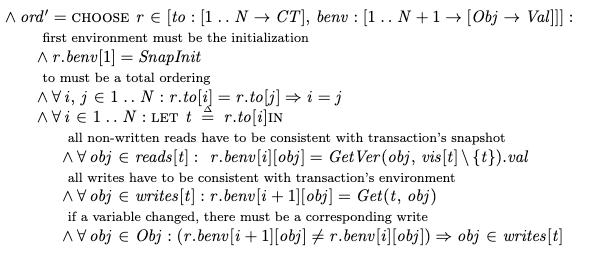

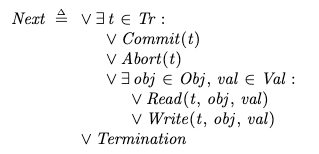

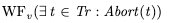

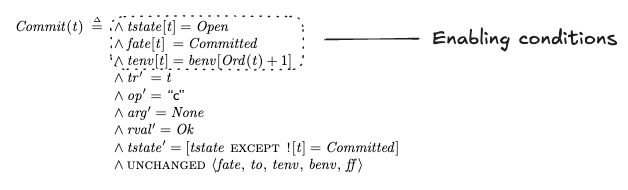

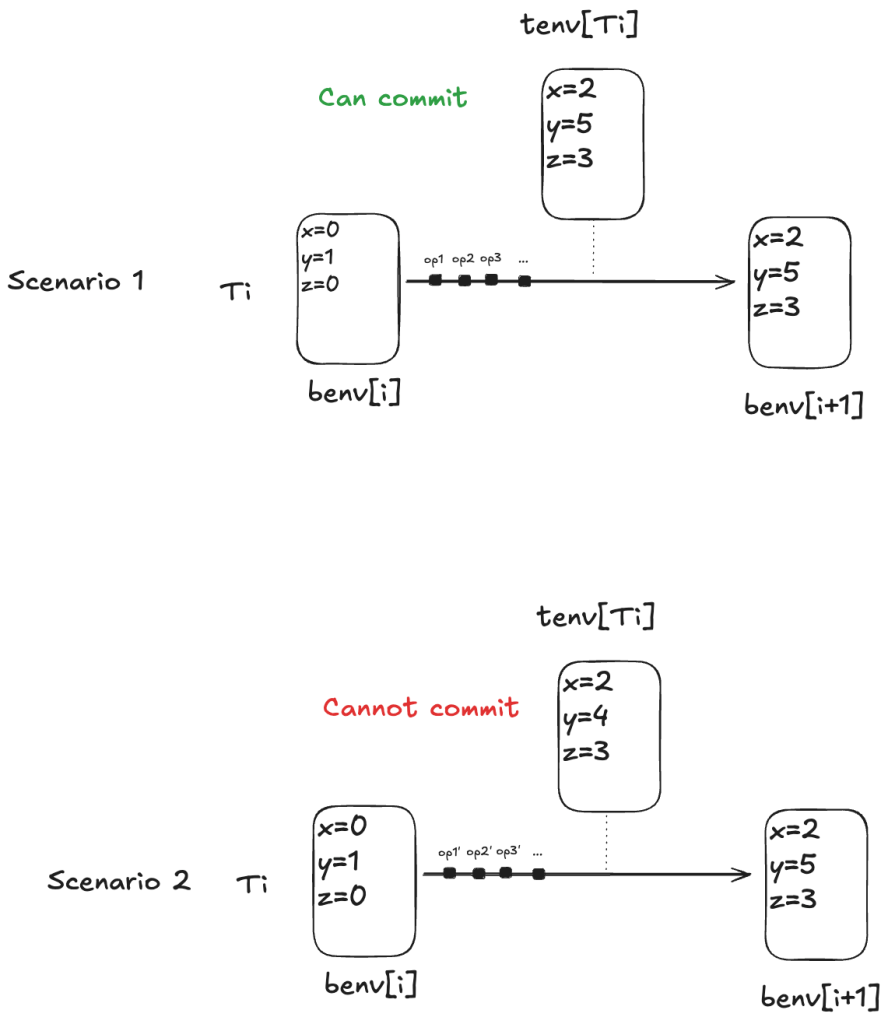

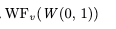

A formal specification language is just a notation for describing a set of behaviors by generating them. In TLA+, this is extremely explicit. All TLA+ have two parts:

- Init – which describes all valid initial states

- Next – which describes how to extend an existing valid behavior to one or more new valid behavior(s)

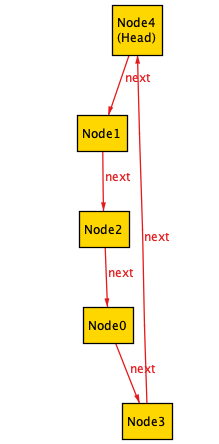

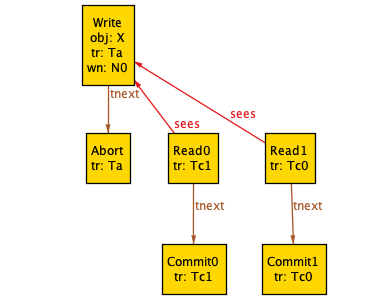

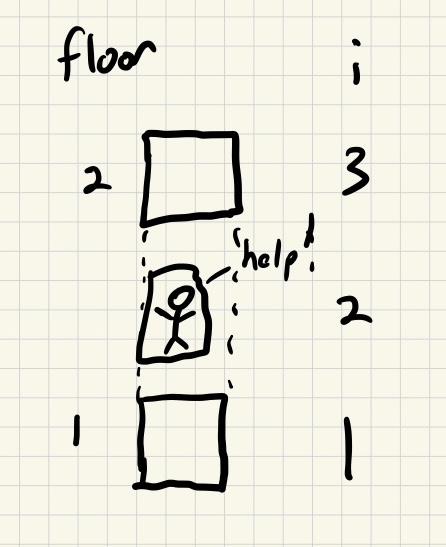

Here’s a visual representation of generating correct behaviors for the counter.

Note how in the case of the counter, there’s only one valid initial state in a behavior: all of the correct behaviors start the same way. After that, when generating a new behavior based on a previous one, whether one behavior or multiple behaviors can be generated depends on the history. If the last event was a method invocation, then there’s only one valid way to extend that behavior, which is the expected response of the request. If the last event was a return of a method, then you can extend the behavior in three different ways, based on the three different methods you can call on the counter.

The (Init, Next) pair describe all of the possible correct behaviors of the counters by generating them.

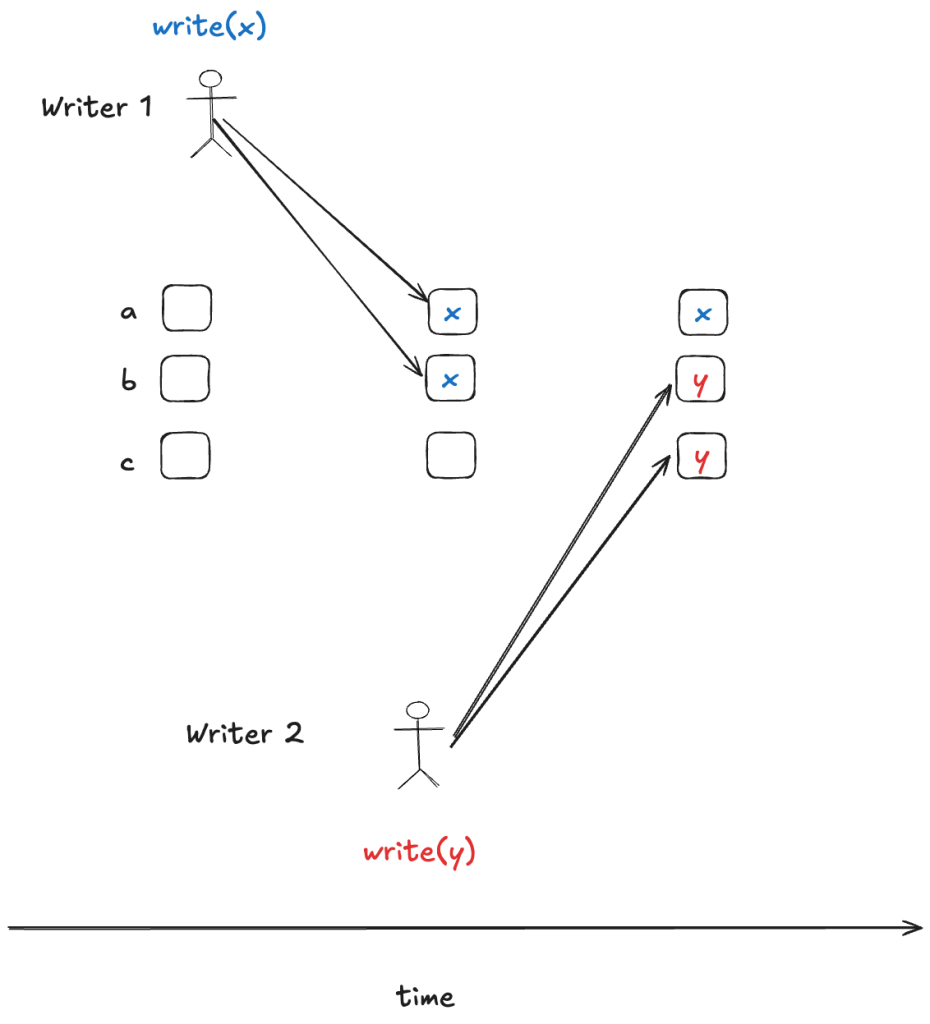

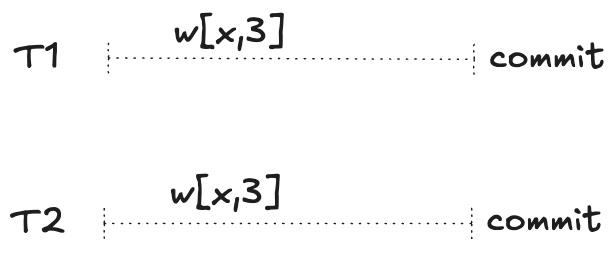

Nondeterminism

One area where formal methods can get confusing for newcomers is that the notation for writing the behavior generator can look like a programming language, particularly when it comes to nondeterminism.

When you’re writing a formal specification, you want to express “here are all of the different ways that you can validly extend this behavior”, hence you get that branching behavior in the diagram in the previous section: you’re generating all of the possible correct behaviors. In a formal specification, when we talk about “nondeterminism”, we mean “there are multiple ways a correct behavior can be extended”, and that includes all of the different potential inputs that we might receive from outside. In formal specifications, nondeterminism is about extending a correct behavior along multiple paths.

On the other hand, in a computer program, when we talk about code being nondeterministic, we mean “we don’t know which path the code is going to take”. In the programming world, we typically use nondeterminism to refer to things like random number generation or race conditions. One notable area where they’re different is that formal specifications treat inputs as a source of nondeterminism, whereas programmers don’t include inputs when they talk about nondeterminism. If you said “user input is one of the sources of nondeterminism”, a formal modeler would nod their head, and a programmer would look at you strangely.

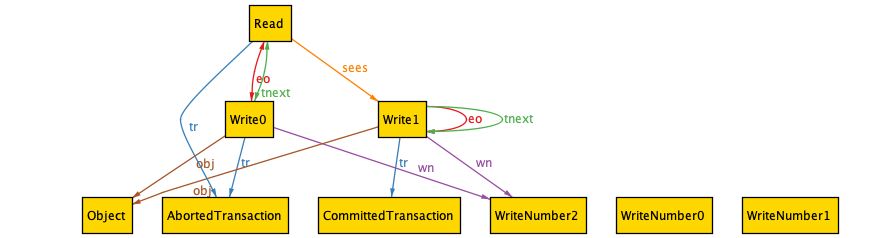

Properties of a spec: sets of behaviors

I’ve been using the expressions correct behavior and behavior satisfies the specification interchangeably. However, in practice, we build formal specifications to help us reason about the correctness of the system we’re trying to build. Just because we’ve written a formal specification doesn’t mean that the specification is actually correct! That means that we can’t treat the formal specification that we build as the correct description of the system in general.

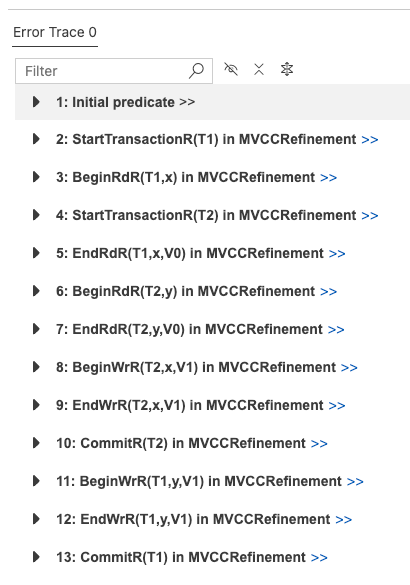

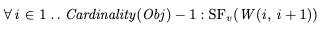

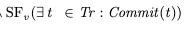

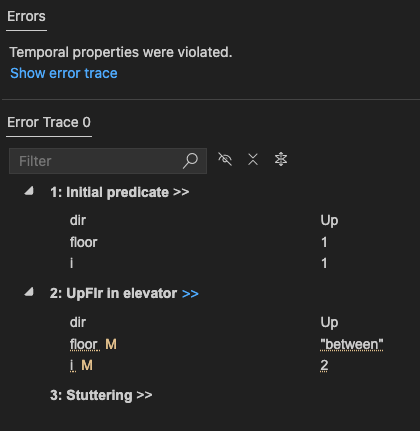

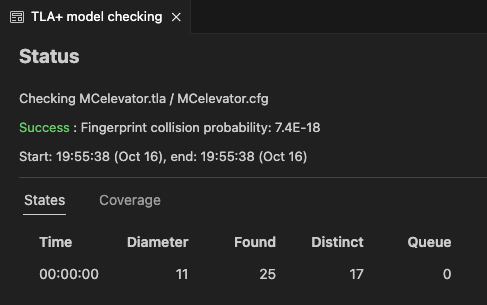

The most frequent tactic people use to reason about their formal specifications is to define correctness properties and use a model-checking tool to check whether their specification conforms to the property or not.

Here’s an example of a property for our counter: the get operation always returns a non-negative value. Let’s give it a name: the no-negative-gets property. If our specification has this property, we don’t know for certain it’s correct. But if it doesn’t have this property, we know for sure something is wrong!

Like a formal specification, a property is nothing more than a set of behaviors! Here’s an example of a behavior that satisfies the no-negative-gets property:

>>> c = Counter()

>>> c.get()

0

>>> c.inc()

>>> c.get()

1

And here’s another one:

>>> c = Counter()

>>> c.get()

5

>>> c.inc()

>>> c.get()

3

Note that the second wrong probably looks wrong to you. We haven’t actually written out a specification for our counter in this post, but if we did, the behavior above would certainly violate it: that’s not how counters work. On the other hand, it still satisfies the no-negative-gets property. In practice, the set of behaviors defined by a property will include behaviors that aren’t in the specification, as depicted below.

When we check that that a spec satisfies a property, we’re checking that Spec is a subset of Property. We just don’t care about the behaviors that are in the Property set but not in the Spec set. What we care about are behaviors that are in Spec that are not in Property. That tells us that our specification can generate behaviors that do not possess the property that we care about.

Consider the property: get always return a positive number. We can call it all-positive-gets. Note that zero is not considered a positive number. Assuming our counter specification starts at zero, here’s a behavior that violates the all-positive-gets property:

>>> c = Counter()

>>> c.get()

0

Thinking in sets

When writing formal specifications, I found that thinking in terms of sets of behaviors was a subtle but significant mind-shift from thinking in terms of writing traditional programs. Where it helped me most is in making sense of the errors I get when debugging my TLA+ specifications using the TLC model checker. After all, it’s when things break is when you really need to understand whats’s going on under the hood. And I promise you, when you write formal specs, things are going to break. That’s why we write them, to find where the breaks are.