A common failure mode in complex systems is that some part of the system hits a limit and falls over. In the software world, we call this phenomenon resource exhaustion, and a classic example of this is running out of memory.

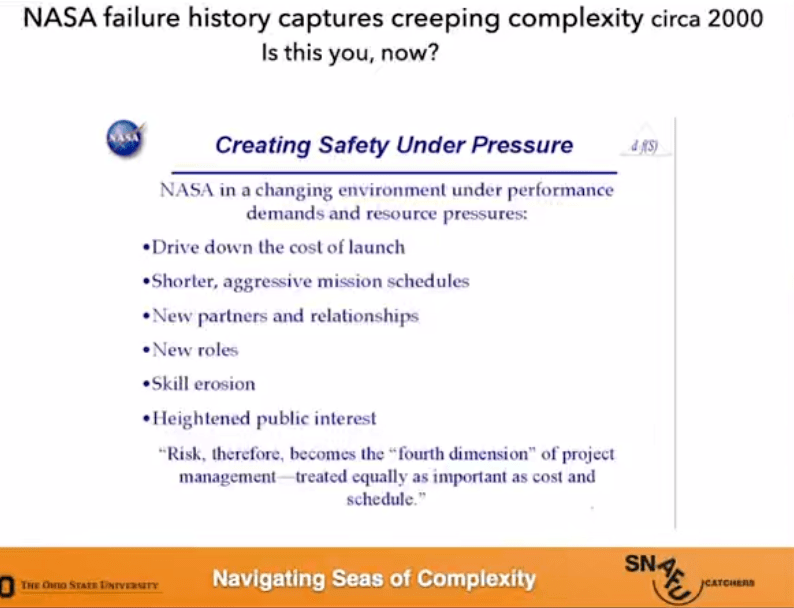

The simplest solution to this problem is to “provision for peak”: to build out the system so that it always has enough resources to handle the theoretical maximum load. Alas, this solution isn’t practical: it’s too expensive. Even if you manage to overprovision the system, over time, it will get stretched to its limits. We need another way to mitigate the risk of overload.

Fortunately, it’s rare for every component of a system to reach its limit simultaneously: while one component might get overloaded, there are likely other components that have capacity to spare. That means that if one component is in trouble, it can borrow resources from another one.

Indeed, we see this sort of behavior in biological systems. In the paper Allostasis: A Model of Predictive Regulation, the neuroscientist Peter Sterling explains why allostasis is a better theory than homeostasis. Readers are probably familiar with the term homeostasis: it refers to how your body maintains factors in a narrow range, like keeping your body temperature around 98.6°F. Allostasis, on the other hand, is about how your body predicts where these sorts of levels should be, based on anticipated need. Your body then takes action to modify the current state of these levels. Here’s Sterling explaining why he thinks allostasis is superior, referencing the idea of borrowing resources across organs (emphasis mine)

A second reason why homeostatic control would be inefficient is that if each organ self-regulated independently, opportunities would be missed for efficient trade-offs. Thus each organ would require its own reserve capacity; this would require additional fuel and blood, and thus more digestive capacity, a larger heart, and so on – to support an expensive infrastructure rarely used. Efficiency requires organs to trade-off resources, that is, to grant each other short-term loans.

The systems we deal with are not individual organisms, but organizations that are made up of groups of people. In organization-style systems, this sort of resource borrowing becomes more complex. Incentives in the system might make me less inclined to lend you resources, even if doing so would lead to better outcomes for the overall system. In his paper The Theory of Graceful Extensibility: Basic rules that govern adaptive systems, David Woods borrows the term reciprocity from Elinor Ostrom to describe this property in a system of one agent being willing to lend resources to another as a necessary ingredient for resilience (emphasis mine):

Will the neighboring units adapt in ways that extend the [capacity for maneuver] of the adaptive unit at risk? Or will the neighboring units behave in ways that further constrict the [capacity for maneuver] of the adaptive unit at risk? Ostrom (2003) has shown that reciprocity is an essential property of networks of adaptive units that produce sustained adaptability.

I couldn’t help thinking of the Sterling and Woods papers when reading the latest issue of Nat Bennett’s Simpler Machines newsletter, titled What was special about Pivotal? Nat’s answer is reciprocity:

This isn’t always how it went at Pivotal. But things happened this way enough that it really did change people’s expectations about what would happen if they co-operated – in the game theory, Prisoner’s Dilemma sense. Pivotal was an environment where you could safely lead with co-operation. Folks very rarely “defected” and screwed you over if you led by trusting them.

People helped each other a lot. They asked for help a lot. We solved a lot of problems much faster than we would have otherwise, because we helped each other so much. We learned much faster because we helped each other so much.

And it was generally worth it to do a lot of things that only really work if everyone’s consistent about them. It was worth it to write tests, because everyone did. It was worth it to spend time fixing and removing flakes from tests, because everyone did. It was worth it to give feedback, because people changed their behavior. It was worth it to suggest improvements, because things actually got better.

There was a lot of reciprocity.

Nat’s piece is a good illustration of the role that culture plays in enabling a resilient organization. I suspect it’s not possible to impose this sort of culture, it has to be fostered. I wish this were more widely appreciated.