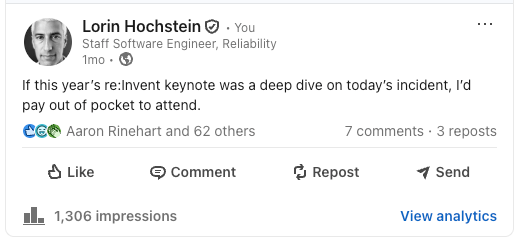

Last month, I made the following remark on LinkedIn about the incident that AWS experienced back in October.

To Amazon’s credit, there was a deep dive talk on the incident at re:Invent! OK, it wasn’t the keynote, but I’m still thrilled that somebody from AWS gave that talk. Kudos to Amazon leadership for green-lighting a detailed talk on the failure mode, and to Craig Howard in particular for giving this talk.

In my opinion, this talk is the most insightful post-incident public artifact that AWS has ever produced, and I really hope they continue to have these sorts of talks after significant outages in the future. It’s a long talk, but it’s worth it. In particular, it goes into more detail about the failure mode than the original write-up.

Tech that improves reliability bit them in this case

This is yet another example of a reliable system that fails through unexpected behavior of a subsystem whose primary purpose was to improve reliability. In particular, this incident involved the unexpected interaction of the following mechanisms, all of which are there to improve reliability.

- Multiple enactor instances – to protect against individual enactor instances failing

- Locking mechanism – to make it easier for engineers to reason about the system behavior

- Cleanup mechanism – to protect against saturating Route 53 by using up all of the records

- Transactional mechanism – to protect against the system getting into a bad state after a partial failure (this is “all succeeds or none succeeds”)

- Rollback mechanism – to be able to recover quickly if a bad plan is deployed

These all sound like good design decisions to me! But in this case, they contributed to an incident, because of an unanticipated interaction with a race condition. Note that many of these are anticipating specific types of failures, but we can never imagine all types of failures, and the ones that we couldn’t imagine are the ones that bite us.

Things that made the incident hard

This talk not only discusses the failure itself, but also the incident response, and what made the incident response more difficult. This was my favorite part of the talk, and it’s the first time I can remember anybody from Amazon talking about the details of incident response like this.

Some of the issues that issues that Howard brought up:

- They used UUIDs as identifiers for plans, which was difficult for the human operators to work with as compared to more human-readable identifiers

- There were so many alerts firing that it took them fifteen minutes to look through all of them and find the one that told them what the underlying issue is

- the logs that were outputted did not make it easy to identify the sequence of events that led to the incidents.

He noted that this illustrates how the “let’s add an alert” approach to dealing with previous incidents can actually hurt you, and that you should think about what will happen in a large future incident, rather than simply reacting to the last one.

Formal modeling and drift

This incident was triggered by a race condition, and race conditions are generally very difficult to identify in development without formal modeling. They had not initialized modeling this aspect of DynamoDB beforehand. When they did build a formal model (using TLA+) after the incident, they discovered that the original design didn’t have this race condition, but later incremental changes to the system did introduce it. This means that, at design time, if they had formally modeled the system, they wouldn’t have caught it then either, because it wasn’t there at design time.

Interestingly, they were able to use AI (Amazon Q, of course) to check correspondence between the model and the code. This gives me some hope that AI might make it a lot easier to keep models and implementation in sync over time, which would increase the value of maintaining these models.

Fumbling towards resilience engineering

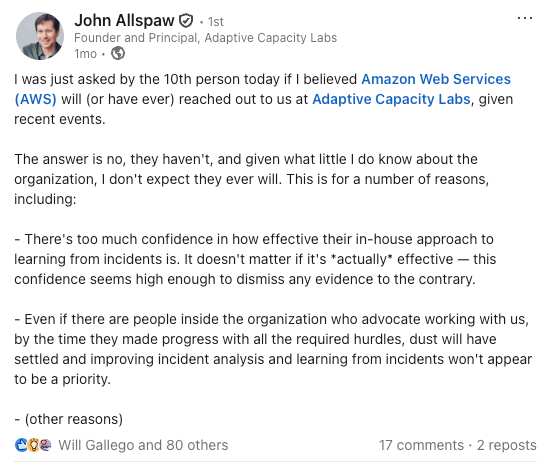

Amazon is, well, not well known for embracing resilience engineering concepts.

Listening to this talk, there were elements of it that gestured in the direction of resilience engineering, which is why I enjoyed it so much. I already wrote about how Howard called out elements that made the incident harder. He also talked about how post-incident analysis can take significant time, and it’s a very different type of work than the heat-of-the-moment diagnostic work. In addition, there were some good discussion in the talk about tradeoffs. For example, he talked about caching tradeoffs in the context of negative DNS caching and how that behavior exacerbated this particular incident. He also spoke about how there are broader lessons that others can learn from this incident, even though you will never experience the specific race condition that they did. These are the kinds of topics that the resilience in software community has been going on about for years now. Hopefully, Amazon will get there.

And while I was happy that this talk spent time on the work of incident response, I wish it had gone farther. Despite the recognition earlier in the talk about how incident response was made more difficult by technical decisions, in the lessons learned section at the end, there was no discussion about “how do we design our system to make it easier for responders to diagnose and mitigate when the next big incident happens?”.

Finally, I still grit my teeth whenever I hear the Amazonian term for their post-incident review process: Correction of Error.