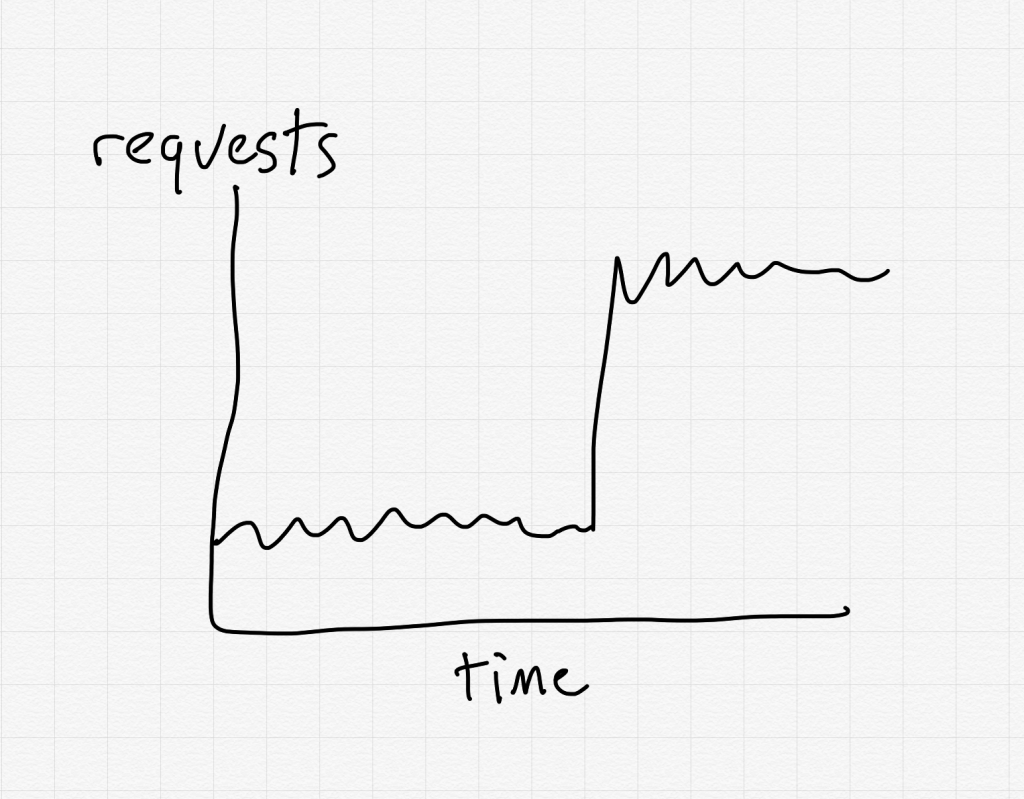

When you deploy a service into production, you need to configure it with enough resources (e.g., CPU, memory) so that it can handle the volume of requests you expect it to receive. You’ll want to provision it so that it can service 100% of the requests when receiving the typical amount of traffic, and you probably want some buffer in there as well.

However, as a good operator, you also know that sometimes your service will receive an unexpected increase in traffic that’s a large enough to push your service beyond the resources that you’ve been provisioned for it, even with that extra buffer.

When your service is overloaded, even though it can’t service 100% of the requests, you want to design it so that it doesn’t simply keel over and service 0% of the requests. There are well-known patterns for designing a service to degrade gracefully in the face of overload, such that it can still service some requests, and that keep it from getting so overloaded that it can’t even recover when the traffic abates. These patterns include rate limiters and circuit breakers. Michael Nygard’s book Release It! is a great source for this, and the concepts he describes have been implemented in libraries such as Hystrix and Resilience4j.

You can think of “expected number of requests” and “too many requests” as two different modes of operation of your service: you want to design it so that it performs well in both modes.

Now, imagine in the graph above, instead of the y-axis being “number of requests seen by the service”, it’s “degree of surprise experienced by the operators”.

As we humans navigate the world, we are constantly taking in sensory input. Imagine if I asked you, at regular intervals, “On a scale of 1-10, how surprised are you about your current observations of the world?”, and I plotted it on a graph like the one above. During a typical day, the way we experience the world isn’t too surprising. However, every so often, our observations of the world just don’t make sense to us. The things we’re seeing just shouldn’t be happening, given our mental models of how the world works. When it’s the software’s behavior that’s surprising, and that surprising behavior has a significant negative impact on the business, we call it an incident.

And, just like a software service behaves differently under a very high rate of inbound requests than it does from the typical rate, your socio-technical system (which includes your software and your people) is going to behave differently under high levels of surprise than it does under typical levels.

Similarly, just like you can build your software system to deal more effectively with overload, you can also influence your socio-technical system to deal more effectively with surprise. That’s really what the research field of resilience engineering is about: understanding how some socio-technical systems are more effective than others when working in high surprise mode.

It’s important to note that being more effective at high surprise mode is not the same as trying to eliminate surprises in the future. Adding more capacity to your software service enables it to handle more traffic, but it doesn’t help deal with the situation where the traffic exceeds even those extra resources. Rather, your system needs to be able to change what it does under overload. Similarly, saying “we are going to make sure we handle this scenario in the future” does nothing to improve your system’s ability to function effectively in high surprise mode.

I promise you, your system is going to enter high surprise mode in the future. The number of failure modes that you have eliminated does nothing to improve your ability to function well when this mode happens. While RCA will eliminate a known failure mode, LFI will help your system function better in high surprise mode.