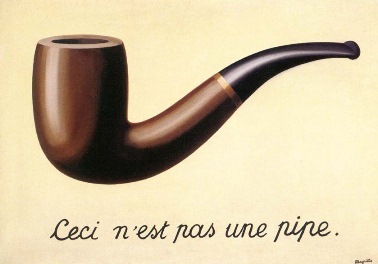

Well, who you gonna believe, me or your own eyes? – Chico Marx (dressed as Groucho), from Duck Soup:

In the ACM Queue article Above the Line, Below the Line, the late safety researcher Richard Cook (of How Complex Systems Fail fame) notes how that we software operators don’t interact directly with the system. Instead, we interact through representations. In particular, we view representations of internal state of the system, and we manipulate these representations in order to effect changes, to control the system. Cook used the term line of representation to describe the split between the world of the technical (software) system and the world of the people who work with the technical system. The people are above the line of representation, and the technical system is below the line.

Above the line of representation are the people, organizations, and processes that shape, direct, and restore the technical artifacts that lie below that line.People who work above the line routinely describe what is below the line using concrete, realistic language.

Yet, remarkably, nothing below the line can be seen or acted upon directly. The displays, keyboards, and mice that constitute the line of representation are the only tangible evidence that anything at all lies below the line. All understandings of what lies below the line are constructed in the sense proposed by Bruno Latour and Steve Woolgar. What we “know”—what we can know—about what lies below the line depends on inferences made from representations that appear on the screens and displays.

In short, we can never actually see or change the system directly, all of our interactions mediated through software interfaces.

In this post, I want to talk about how this fact can manifest as incidents, and that our solutions rarely consider this problem. Let’s start off, as we so often do in the safety world, with the Three Mile Island accident.

Three Mile Island and the indicator light

I assume the reader has some familiarity with the partial meltdown that occurred at the Three Mile Island nuclear plant back in 1979. As it happens, there’s a great series of lectures by Cook on accidents. The topic of his first lecture is about how Three Mile Island changed the way safety specialists thought about the nature of accidents.

Here I want to focus on just one aspect of this incident: a particular indicator light in the Three Mile Island control room. During this incident, there was a type of pressure relief valve called a pilot-operated relief valve (PORV) that was stuck open. However, the indicator light for the state of this valve was off, which the operators interpreted (incorrectly, alas) as the valve being closed. Here I’ll quote the wikipedia article:

A light on a control panel, installed after the PORV had stuck open during startup testing, came on when the PORV opened. When that light—labeled Light on – RC-RV2 open —went out, the operators believed that the valve was closed. In fact, the light when on only indicated that the PORV pilot valve’s solenoid was powered, not the actual status of the PORV. While the main relief valve was stuck open, the operators believed the unlighted lamp meant the valve was shut. As a result, they did not correctly diagnose the problem for several hours.

What I found notable was the article’s comment about lack of operator training to handle this specific scenario, a common trope in incident analysis.

The operators had not been trained to understand the ambiguous nature of the PORV indicator and to look for alternative confirmation that the main relief valve was closed. A downstream temperature indicator, the sensor for which was located in the tail pipe between the pilot-operated relief valve and the pressurizer relief tank, could have hinted at a stuck valve had operators noticed its higher-than-normal reading. It was not, however, part of the “safety grade” suite of indicators designed to be used after an incident, and personnel had not been trained to use it. Its location behind the seven-foot-high instrument panel also meant that it was effectively out of sight.

Now, consider what happens if the agent acting on these sensors is an automated control system instead of a human operator.

Sensors, automation, and accidents: cases from aviation

In the aviation world, we have a combination of automation and human operators (pilots) who work together in real-time. The assumption is that if something goes wrong with the automation, the human can quickly take over and deal with the problem. But automation can make things too difficult for a human to be able to compensate for, and automation can be particularly vulnerable to sensor problems, as we can see in the following accidents:

Bombardier Learjet 60 accident, 2008

On September 19, 2008, in Columbia, South Carolina, a Bombardier Learjet 60 overran the runway during a rejected takeoff. As a consequence, four people aboard the plane, including the captain and first officer, were killed. In this case, the sensor issues were due to damage to electronics in the wheel well area after underinflated tires on the landing gear exploded.

The pilots reversed thrust to slow down the plane. However, the tires on the plane were under-inflated, and they exploded. As a result of the tire explosion, sensors in the wheel well area of the plane were damaged.

The thrust reverse system relies on sensor data to determine whether reversing thrust is a safe operation. Because of the sensor damage, the system determined that it was not safe to reverse thrust, and instead increased forward thrust. From the NTSB report:

In this situation, the EECs would transition from the reverse thrust power schedule to the

forward thrust power schedule during about a 2-second transition through idle power. During the entire sequence, the thrust reverser levers in the cockpit would remain in the reverse thrust idle position (as selected by the pilot) while the engines produced forward thrust. Because both the thrust reverser levers and the forward thrust levers share common RVDTs (one for the left engine and one for the right engine), the EECs, which receive TLA information from the RVDTs, would signal the engines to produce a level of forward thrust that generally corresponds with the level of reverse thrust commanded; that is, a pilot commanding full reverse thrust (for maximum deceleration of the airplane) would instead receive high levels of forward thrust (accelerating the airplane) according to the forward thrust power schedule

(My initial source for this was John Thomas’s slides.)

Air France 447, 2009

On June 1, 2009, Air France 447 crashed, killing all passengers and crew. The plane was an Airbus A330-200. In this accident, the sensor problem is believed to be caused by ice crystals that accumulated inside of pitot tube sensors, creating a blockage which lead to erroneous readings. Here’s a quote from an excellent Vanity Fair article on the crash:

Just after 11:10 P.M., as a result of the blockage, all three of the cockpit’s airspeed indications failed, dropping to impossibly low values. Also as a result of the blockage, the indications of altitude blipped down by an unimportant 360 feet. Neither pilot had time to notice these readings before the autopilot, reacting to the loss of valid airspeed data, disengaged from the control system and sounded the first of many alarms—an electronic “cavalry charge.” For similar reasons, the automatic throttles shifted modes, locking onto the current thrust, and the fly-by-wire control system, which needs airspeed data to function at full capacity, reconfigured itself from Normal Law into a reduced regime called Alternate Law, which eliminated stall protection and changed the nature of roll control so that in this one sense the A330 now handled like a conventional airplane. All of this was necessary, minimal, and a logical response by the machine.

This is what the safety researcher David Woods refers to as bumpy transfer of control, where the humans must suddenly and unexpectedly take over control of an automated system, which can lead to disastrous consequences.

Boeing 737 MAX 8 (2018, 2019)

On October 29, 2018, Lion Air Flight 610 crashed thirteen minutes after takeoff, killing everyone on board. Five months later, on March 10, 2019, Ethiopian Airlines Flight 302 crashed six minutes after takeoff, also killing everyone on board. Both planes were Boeing 737 MAX 8. In both cases, the sensor problem was related to the angle-of-attack (AOA) sensor.

Lion Air Flight 610 investigation report:

The replacement AOA sensor that was installed on the accident aircraft had

been mis-calibrated during an earlier repair. This mis-calibration was not

detected during the repair.

Ethiopian Airline Flight 302 investigation report:

Shortly after liftoff, the left Angle of Attack sensor recorded value became erroneous and the left stick shaker activated and remained active until near the end of the recording.

An automation subsystem in the 737 MAX called Maneuvering Characteristics Augmentation System (MCAS) automatically pushed the nose down in response to the AOA sensor data.

What should we take away from these?

Here I’ve given examples from aviation, but sensor-automation problems are not specific to that domain. Here are a few of my own takeaways.

We designers can’t assume sensor data will be correct

The kinds of safety automation subsystems we build in tech are pretty much always closed-loop control systems. When designing such systems in the tech world, how often have you heard someone ask, “what happens if there’s a problem with the sensor data that the system is reacting to?”

This goes back to the line of representation problem: that no agent ever gets access to the true state of the system, it only gets access to some sort of representation. The irony here is that it doesn’t just apply to humans (above the line) making sense of signals, it also applies to technical system components (below the line!) making sense of signals from other technical components.

Designing a system that is safe in the face of sensor problems is hard

Again, from the NTSB report of the Learjet 60 crash:

Learjet engineering personnel indicated that the uncommanded stowage of the thrust reversers in the event of any system loss or malfunction is part of a fail-safe design that ensures that a system anomaly cannot result in a thrust reverser deployment in flight, which could adversely affect the airplane’s controllability. The design is intended to reduce the pilot’s emergency procedures workload and prevent potential mistakes that could exacerbate an abnormal situation.

The thrust reverser system behavior was designed by aerospace engineers to increase safety, and ended up making things worse! Good luck imagining all of these sorts of scenarios when you design your systems to increase safety.

Even humans struggle in the face of sensor problems

People are better equipped to handle sensor problems than automation, because we don’t seem to be able to build automation that can handle all of the possible kinds of sensor problems that we might throw at a problem.

But even for humans, sensor problems are difficult. While we’ll eventually figure out what’s going on, we’ll still struggle in the face of conflicting signals, as anyone who has responded to an incident can tell you. And in high-tempo situations, where we need to respond quickly enough or something terrible will happen (like in the Air France 447 case), we simply might not be able to respond quickly enough.

Instead of focusing on building the perfect fail-safe system to prevent this next time, I wish we’d spend more time thinking about, “how can we help the human figure out what the heck is happening when the input signals don’t seem to make sense”.

Your post made me think of a long ago incident I had when I had dental implant surgery.. the drill was supposedly overheating and kept shutting off. Eventually, the surgeon, knowing that by simply rebooting the machine it would clear the fault (and they had been needing a service call) had a 3rd person come in whose job was to reboot the machine to clear the fault. The endodontist and their assistant would then continue drilling.

To me, this was a harrowing experience that resulted in this blog post: https://wirfs-brock.com/rebecca/blog/2006/04/19/workarounds-vs-workthroughs/ I’ve always thought people should be in control of systems (and when they notice that something isn’t as a sensor says it is, should be able to override that faulty value)… however, you just pointed out a combination of “corrective” behaviors that are automatically put in place. Even more harrowing. We need to give people more information so they can make informed decisions, for sure.

Your post made me think of a long ago incident I had when I had dental implant surgery.. the drill was supposedly overheating and kept shutting off. Eventually, the surgeon, knowing that by simply rebooting the machine it would clear the fault (and they had been needing a service call) had a 3rd person come in whose job was to reboot the machine to clear the fault. The endodontist and their assistant would then continue drilling.

To me, this was a harrowing experience that resulted in this blog post: https://wirfs-brock.com/rebecca/blog/2006/04/19/workarounds-vs-workthroughs/ I’ve always thought people should be in control of systems (and when they notice that something isn’t as a sensor says it is, should be able to override that faulty value)… however, you just pointed out a combination of “corrective” behaviors that are automatically put in place. Even more harrowing. We need to give people more information so they can make informed decisions, for sure.