Today’s public incident writeup comes courtesy of Brendan Humphries, the CTO of Canva. Like so many other incidents that came before, this is another tale of saturation, where the failure mode involves overload. There’s a lot of great detail in Humpries’s write-up, and I recommend you read it directly in addition to this post.

What happened at Canva

Trigger: deploying a new version of a page

The trigger for this incident was Canva deploying a new version of their editor page. It’s notable that there was nothing wrong with this new version. The incident wasn’t triggered by a bug in the code in the new version, or even by some unexpected emergent behavior in the code of this version. No, while the incident was triggered by a deploy, the changes from the previous version are immaterial to this outage. Rather, it was the system behavior that emerged from clients downloading the new version that led to the outage. Specifically, it was clients downloading the new javascript files from the CDN that set the ball in motion.

A stale traffic rule

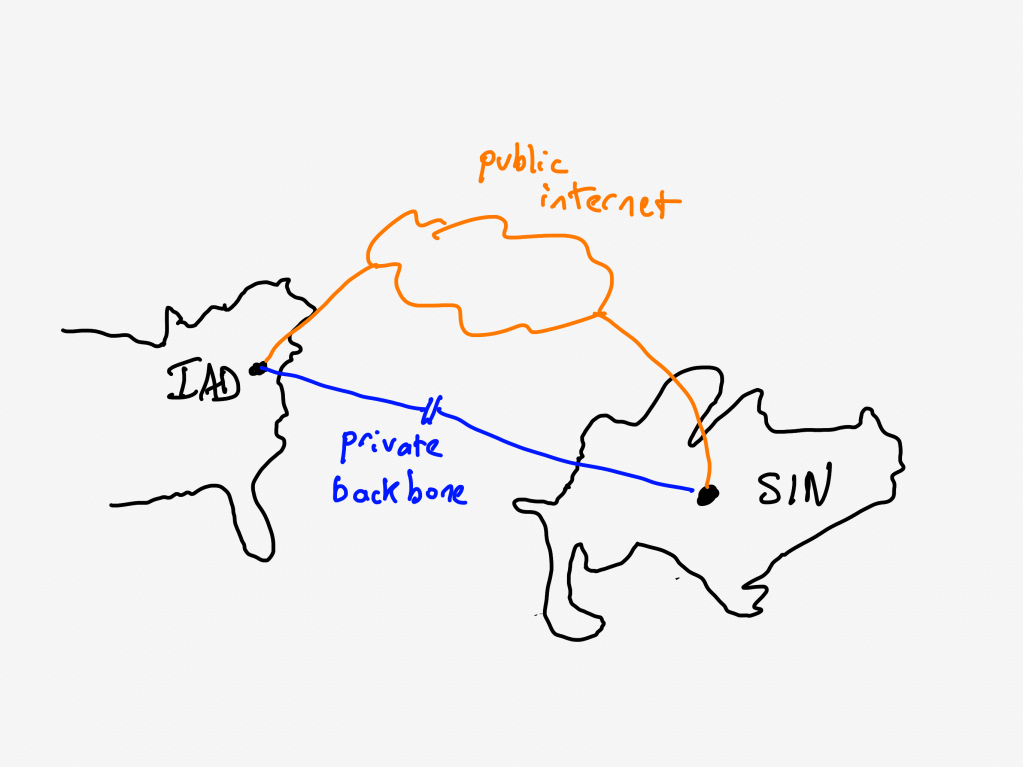

Canva uses Cloudflare as their CDN. Being a CDN, Cloudflare has datacenters all over the world., which are interconnected by a private backbone. Now, I’m not a networking person, but my basic understanding of private backbones is that CDNs lease fibre-optic lines from telecom companies and use these leased lines to ensure that they have dedicated network connectivity and bandwidth between their sites.

Unfortunately for Canva, there was a previously unknown issue on Cloudflare’s side: Cloudflare Wasn’t using their dedicated fibre-optic lines to route traffic between their Northern Virginia and Singapore datacenters. That traffic was instead, unintentionally, going over the public internet.

[A] stale rule in Cloudflare’s traffic management system [that] was sending user IPv6 traffic over public transit between Ashburn and Singapore instead of its default route over the private backbone.

The routes that this traffic took suffered from considerable packet loss. For Canva users in Asia, this meant that they experienced massive increases in latency when their web browsers attempted to fetch the javascript static assets from the CDN.

A stale rule like this is the kind of issue that the safety researcher James Reason calls a latent pathogen. It’s a problem that remains unnoticed until it emerges as a contributor to an incident.

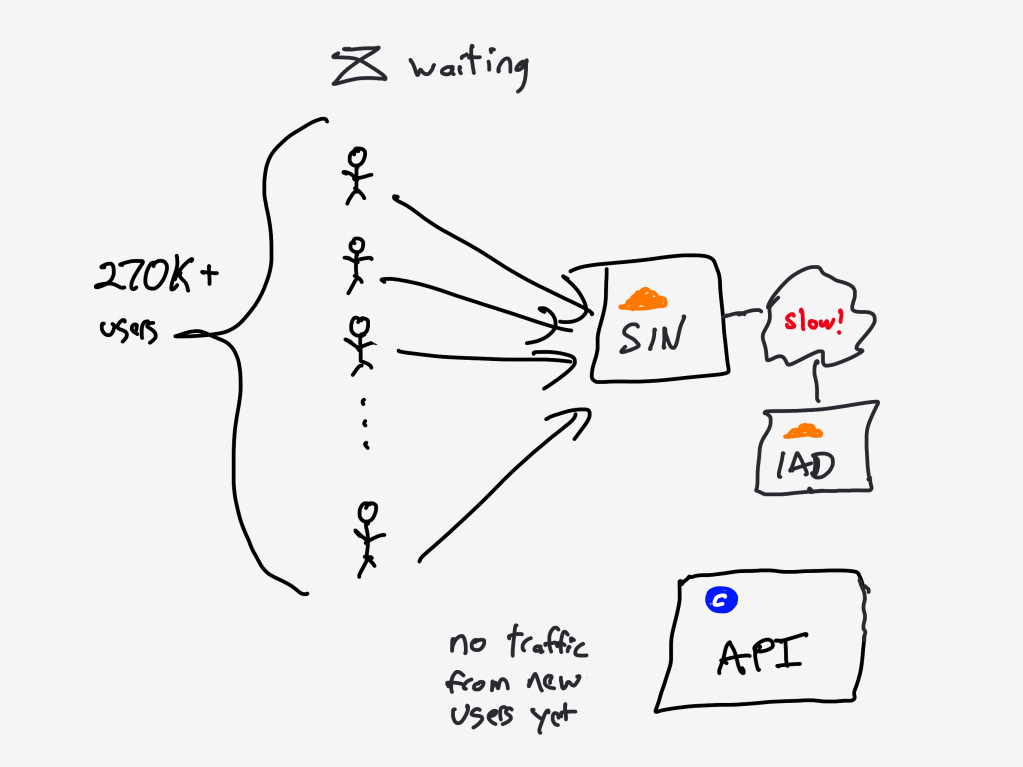

High latency synchronizes the callers

Normally, an increase in errors would cause our canary system to abort a deployment. However, in this case, no errors were recorded because requests didn’t complete. As a result, over 270,000+ user requests for the JavaScript file waited on the same cache stream. This created a backlog of requests from users in Southeast Asia.

The first client attempts to fetch the new Javascript files from the CDN, but the files aren’t there yet, the CDN must fetch the files from the origin. Because of the added latency, this takes a long time.

During this time, other clients connect, and attempt to fetch the javascript from the CDN. But the CDN has not yet been populated with the files from the origin, that transfer is still in progress.

As Cloudflare notes in this blog post, when all subsequent clients request access to a file that is in the process of being populated in the cache, they must wait until the file has been cached before they can download the file. Except that Cloudflare has implemented functionality called Concurrent Streaming Acceleration which permits multiple clients to simultaneously download a file that is still in the process of being downloaded from the origin server.

The resulting behavior is that the CDN now behaves effectively as a barrier, with all of the clients slowly but simultaneously downloading the assets. With a traditional barrier, the processes who are waiting can proceed once all processes have entered in the barrier. This isn’t quite the same, as the clients who are waiting can all proceed once the CDN completes downloading the asset from the origin.

The transfer completes, the herd thunders

At 9:07 AM UTC, the asset fetch completed, and all 270,000+ pending requests were completed simultaneously.

20 minutes after Canva deployed the new Javascript assets to the origin server, the clients completed fetching them. The next action the clients take is to call Canva’s API service.

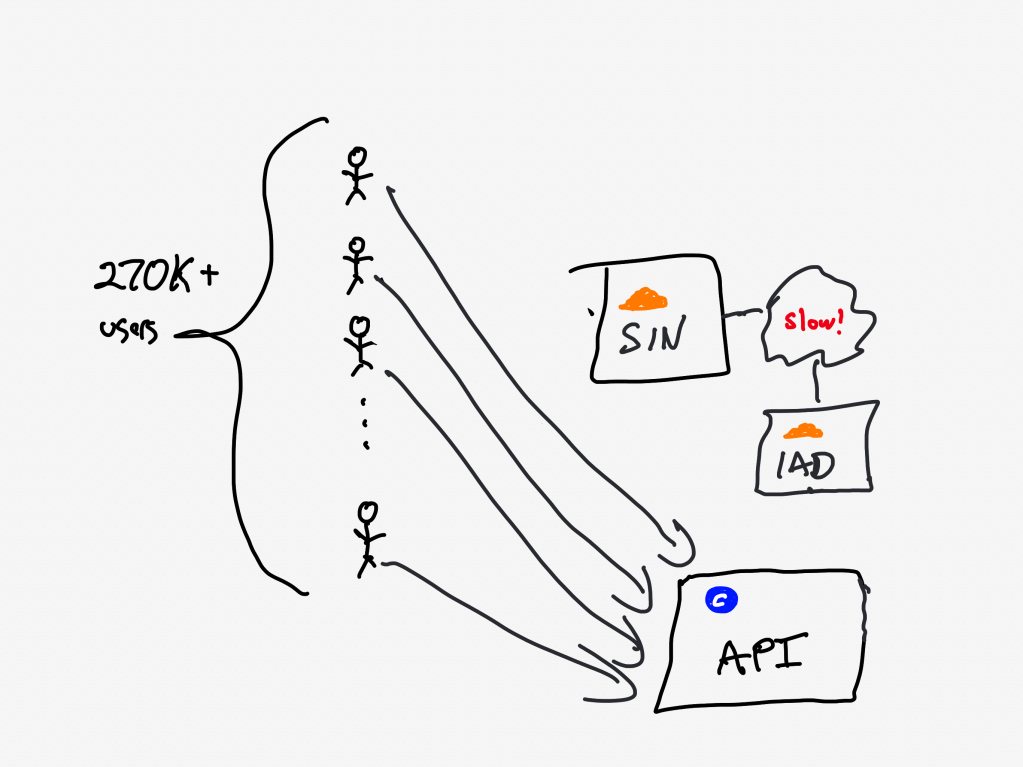

With the JavaScript file now accessible, client devices resumed loading the editor, including the previously blocked object panel. The object panel loaded simultaneously across all waiting devices, resulting in a thundering herd of 1.5 million requests per second to the API Gateway — 3x the typical peak load.

There’s one more issue that made this situation even worse: a known performance issue in the API gateway that was slated to be fixed.

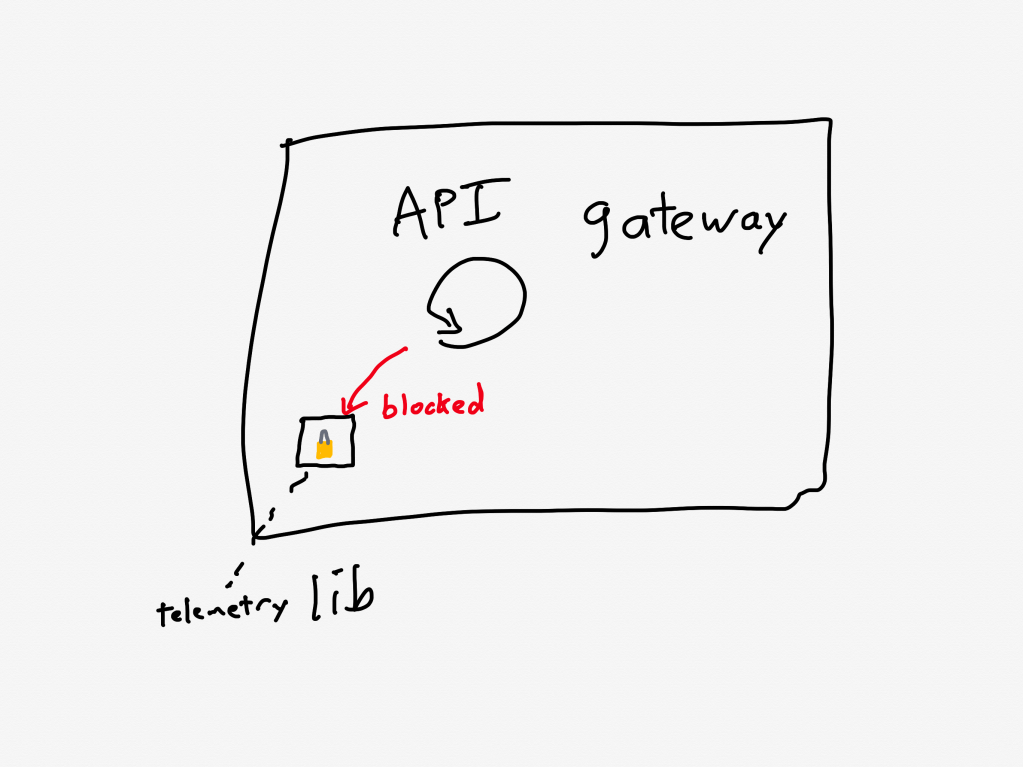

A problematic call pattern to a library reduces service throughput

The API Gateways use an event loop model, where code running on event loop threads must not perform any blocking operations.

Two common threading models for request-response services are thread-per-request and async. For services that are I/O-bound (i.e., most of the time servicing each request is spent waiting for I/O operations to complete, typically networking operations), the async model has the potential to achieve better throughput. That’s because the concurrency of the thread-per-request model is limited by the number of operating-system threads. The async model services multiple requests per thread, and so it doesn’t suffer from the thread bottleneck. Canva’s API gateway implements the async model using the popular Netty library.

One of the drawbacks of the async model is the risk associated with the active thread getting blocked, because this can result in a significant performance penalty. The async model multiplexes multiple requests across an individual thread, and none of those requests can make progress when that thread is blocked. Programmers writing code in a service that uses the async model need to take care to minimize the number of blocking calls.

Prior to this incident, we’d made changes to our telemetry library code, inadvertently introducing a performance regression. The change caused certain metrics to be re-registered each time a new value was recorded. This re-registration occurred under a lock within a third-party library.

In Canva’s case, the API gateway logic was making calls to a third-party telemetry library. They were calling the library in such a way that it took a lock, which is a blocking call. This reduced the effective throughput that the API gateway could handle.

Although the issue had already been identified and a fix had entered our release process the day of the incident, we’d underestimated the impact of the bug and didn’t expedite deploying the fix. This meant it wasn’t deployed before the incident occurred.

Ironically, they were aware of this problematic call pattern, and they were planning on deploying a fix the day of the incident(!).

As an aside, it’s worth noting the role of telemetry logic behavior in the recent OpenAI incident, and in the locking behavior of tracing library in a complex performance issue that Netflix experienced. Observability giveth reliability, and observability taketh reliability away.

Canva is now in a situation where the API gateway is receiving much more traffic than it was provisioned to handle, is also suffering from a performance regression that reduces its ability to handle traffic even more.

Now let’s look at how the system behaved under these conditions.

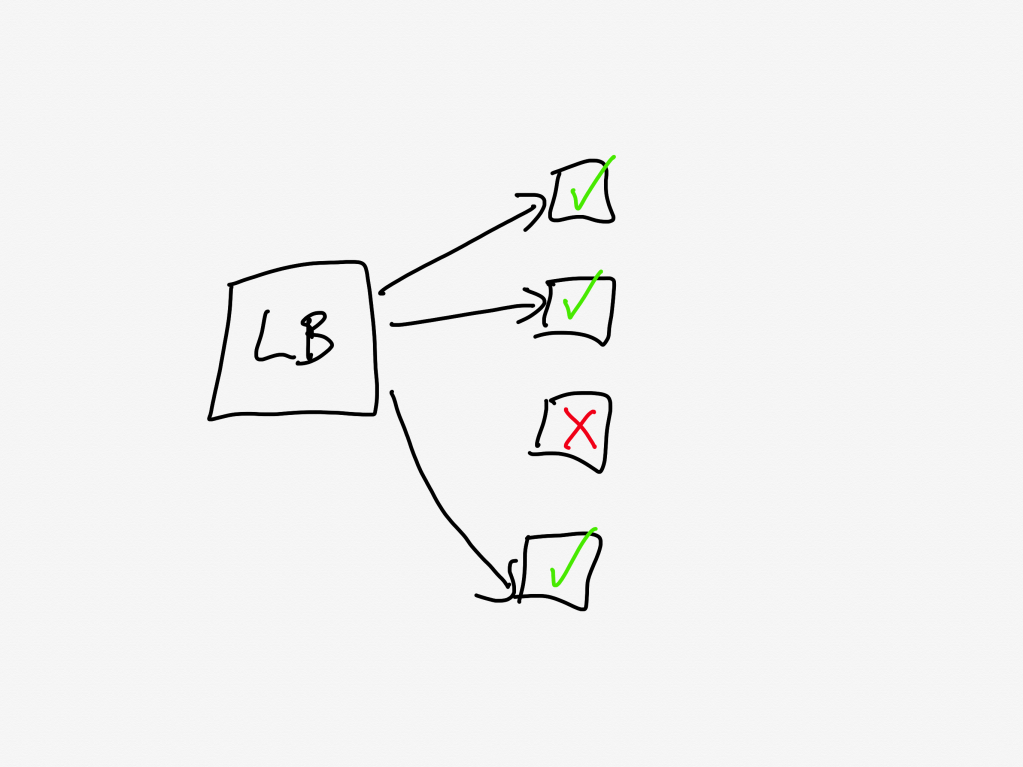

The load balancer turns into an overload balancer

Because the API Gateway tasks were failing to handle the requests in a timely manner, the load balancers started opening new connections to the already overloaded tasks, further increasing memory pressure.

A load balancer sits in front of a service and distributes the incoming requests across the units of compute. Canva runs atop ECS, so the individual units are called tasks, and the group is called a cluster (you can think of these as being equivalent to pods and replicasets in Kubernetes-land).

The load balancer will only send requests to a task that is healthy. If a task is unhealthy, then it stops being considered as a candidate target destination for the load balancer. This yields good results if the overall cluster is provisioned to handle the load: the traffic gets redirected away from the unhealthy tasks and onto the healthy ones.

But now consider the scenario where all of the tasks are operating close to capacity. As tasks go unhealthy, the load balancer will redistribute the load to the remaining “healthy” tasks, which increases the likelihood those tasks gets pushed into an unhealthy state.

This is a classic example of a positive feedback loop: the more tasks go unhealthy, the more traffic the healthy nodes received, the more likely those tasks will go unhealthy as well.

Autoscaling can’t keep pace

So, now the system is saturated, and the load balancer is effectively making things worse. Instead of shedding load, it’s concentrating load on the tasks that aren’t overloaded yet.

Now, this is the cloud, and the cloud is elastic, and we have a wonderful automation system called the autoscaler that can help us in situations of overload by automating provisioning new capacity.

Only, there’s a problem here, and that’s that the autoscaler simply can’t scale up fast enough. And the reason it can’t scale up fast enough is because of another automation system that’s intended to help in times of overload: Linux’s OOM killer.

The growth of off-heap memory caused the Linux Out Of Memory Killer to terminate all of the running containers in the first 2 minutes, causing a cascading failure across all API Gateway tasks. This outpaced our autoscaling capability, ultimately leading to all requests to canva.com failing.

Operating systems need access to free memory in order to function properly. When all of the memory is consumed by running processes, the operating system runs into trouble. To guard against this, Linux has a feature called the OOM killer which will automatically terminate a process when the operating system is running too low on memory. This frees up memory, enabling the OS to keep functioning.

So, you have the autoscaler which is adding new tasks, and the OOM killer which is quickly destroying existing tasks that have become overloaded.

It’s notable that Humphries uses the term outpaced. This sort of scenario is a common failure mode in complex system failures, where the system gets into a state where it can’t keep up. This phenomenon is called decompensation. Here’s resilience engineering pioneer David Woods describing decompensation on John Willis’s Profound Podcast:

And lag is really saturation in time. That’s what we call decompensation, right? I can’t keep pace, right? Events are moving forward faster. Trouble is building and compounding faster than I, than the team, than the response system can decide on and deploy actions to affect. So I can’t keep pace. – David Woods

Adapting the system to bring it back up

At this point, the API gateway cluster is completely overwhelmed. From the timeline:

9:07 AM UTC – Network issue resolved, but the backlog of queued requests result in a spike of 1.5 million requests per second to the API gateway.

9:08 AM UTC – API Gateway tasks begin failing due to memory exhaustion, leading to a full collapse.

When your system is suffering from overload, there are basically two strategies:

- increase the capacity

- reduce the load

Wisely, the Canva engineers pursued both strategies in parallel.

Max capacity, but it still isn’t enough

We attempted to work around this issue by significantly increasing the desired task count manually. Unfortunately, it didn’t mitigate the issue of tasks being quickly terminated.

The engineers tried to increase capacity manually, but even with the manual scaling, the load was too much: the OOM killer was taking the tasks down too quickly for the system to get back to a healthy state.

Load shedding, human operator edition

The engineers had to improvise a load shedding solution in the moment. The approach they took was to block traffic the CDN layer, using Cloudflare.

At 9:29 AM UTC, we added a temporary Cloudflare firewall rule to block all traffic at the CDN. This prevented any traffic reaching the API Gateway, allowing new tasks to start up without being overwhelmed with incoming requests. We later redirected canva.com to our status page to make it clear to users that we were experiencing an incident.

It’s worth noting here that while Cloudflare contributed to this incident with the stale rule, the fact that they could dynamically configure Cloudflare firewall rules meant that Cloudflare also contributed to the mitigation of this incident.

Ramping the traffic back up

Here they turned off all of their traffic to give their system a chance to go back to healthy. But a healthy system under zero load behaves differently from a healthy system under typical load. If you just go back from zero to typical, there’s a risk that you push the system back into an unhealthy state. (One common problem is that autoscaling will have scaled down multiple services due when there’s no load).

Once the number of healthy API Gateway tasks stabilized to a level we were comfortable with, we incrementally restored traffic to canva.com. Starting with Australian users under strict rate limits, we gradually increased the traffic flow to ensure stability before scaling further.

The Canva engineers had the good judgment to ramp up the traffic incrementally rather than turn it back on all at once. They started restoring at 9:45 AM UTC, and were back to taking full traffic at 10:04 AM.

Some general observations

All functional requirements met

I always like to call out situations where, from a functional point of view, everything was actually working fine. In this case, even though there was a stale rule in the Cloudflare traffic management system, and there was a performance regression in the API gateway, everything was working correctly from a functional perspective: packets were still being routed between Singapore and Northern Virginia, and the API gateway was still returning the proper responses for individual requests before it got overloaded.

Rather, these two issues were both performance problems. Performance problems are much harder to spot, and the worst are the ones that you don’t notice until you’re under heavy load.

The irony is that, as an organization gets better at catching functional bugs before they hit production, more and more of the production incidents they face will be related to these more difficult-to-detect-early performance issues.

Automated systems made the problem worse

There were a number of automated systems in play whose behavior made this incident more difficult to deal with.

The Concurrent Streaming Acceleration functionality synchronized the requests from the clients. The OOM killer reduced the time it took for a task to be seen as unhealthy by the load balancer, and the load balancer in turn increased the rate at which tasks went unhealthy.

None of these systems were designed to handle this sort of situation, so they could not automatically change their behavior.

The human operators changed the way the system behaved

It was up to the incident responders to adapt the behavior of the system, to change the way it functioned in order to get it back to a healthy state. They were able to leverage an existing resource, Cloudflare’s firewall functionality, to accomplish this. Based on the description of the action items, I suspect they had never used Cloudflare’s firewall to do this type of load shedding before. But it worked! They successfully adapted the system behavior.

We’re building a detailed internal runbook to make sure we can granularly reroute, block, and then progressively scale up traffic. We’ll use this runbook to quickly mitigate any similar incidents in the future.

This is a classic example of resilience, of acting to reconfigure the behavior of your system when it enters a state that it wasn’t originally designed to handle.

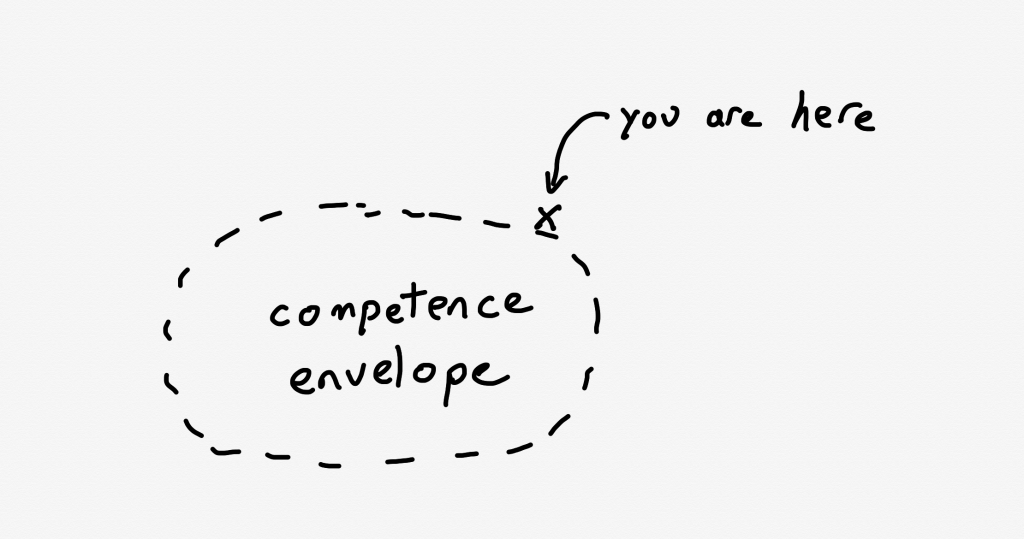

As I’ve written about previously, Woods talks about the idea of a competence envelope. The competence envelope is sort of a conceptual space of the types of inputs that your system can handle. Incidents occur when your system is pushed to operate outside of its competence envelope, such as when it gets more load than it is provisioned to handle:

The competence envelope is a good way to think about the difference between robustness and resilience. You can think of robustness as describing the competence envelope itself: a more robust system may have a larger competence envelope, it is designed to handle a broader range of problems.

However, every system has a finite competence envelope. The difference between a resilient and a brittle system is how that system behaves when it is pushed just outside of its competence envelope.

A resilient system can change the way it behaves when pushed outside of the competence envelope due to an incident in order to extend the competence envelope so that it can handle the incident. That’s why we say it has adaptive capacity. On the other hand, a brittle system is one that cannot adapt effectively when it exceeds its competence envelope. A system can be very robust, but also brittle: it may be able to handle a very wide range of problems, but when it faces a scenario it wasn’t designed to handle, it can fall over hard.

The sort of adaptation that resilience demands requires human operators: our automation simply doesn’t have a sophisticated enough model of the world to be able to handle situations like the one that Canva found itself in.

In general, action items after an incident focus on expanding the competence envelope: making changes to the system to handle the scenario that just happened. Improving adaptive capacity involves different kind of work than improving system robustness.

We need to build in the ability to reconfigure our systems in advance, without knowing exactly what sorts of changes we’ll need to make. The Canva engineers had some powerful operational knobs at their disposal through the Cloudflare firewall configuration. This allowed them to make changes. The more powerful and generic these sorts of dynamic configuration features are, the more room for maneuver we have. Of course, dynamic configuration is also dangerous, and is itself a contributor to incidents. Too often we focus solely on the dangers of such functionality in creating incidents, without seeing its ability to help us reconfigure the system to mitigate incidents.

Finally, these sorts of operator interfaces are of no use if the responders aren’t familiar with them. Ultimately, the more your responders know about the system, the better position they’ll be in to implement these adaptations. Changing an unhealthy system is dangerous: no matter how bad things are, you can always accidentally make things worse. The more knowledge about the system you can bring to bear during an incident, the better position you’ll be in to adaptive your system to extend that competence envelope.

One thought on “The Canva outage: another tale of saturation and resilience”