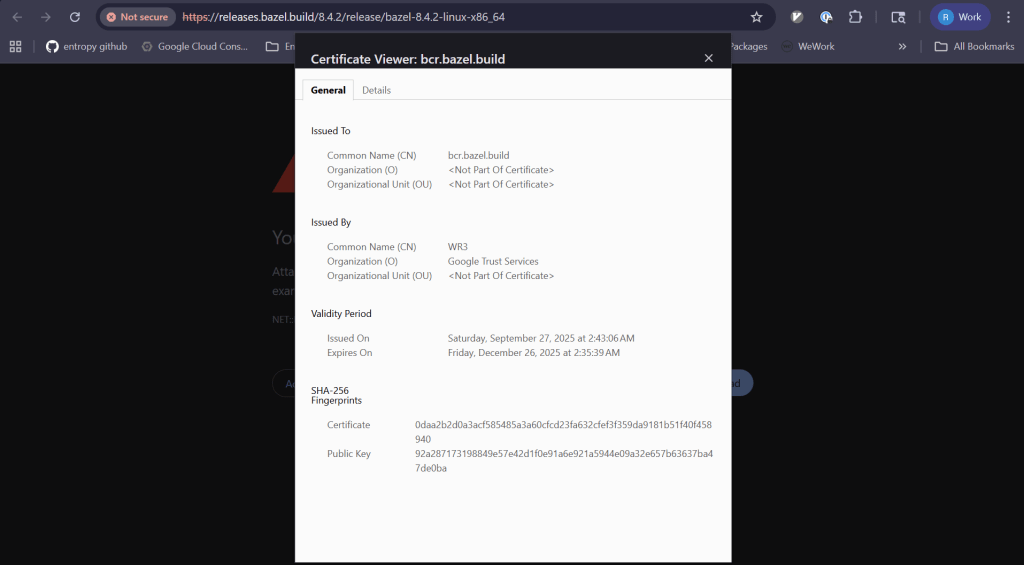

Yesterday, the Bazel team at Google did not have a very Merry Boxing Day. An SSL certificate expired for https://bcr.bazel.build and https://releases.bazel.build, as shown in this screenshot from the github issue.

This expired certificate apparently broke the build workflow of users who use Bazel, who were faced with the following error message:

ERROR: Error computing the main repository mapping: Error accessing registry https://bcr.bazel.build/: Failed to fetch registry file https://bcr.bazel.build/modules/platforms/0.0.7/MODULE.bazel: PKIX path validation failed: java.security.cert.CertPathValidatorException: validity check failed

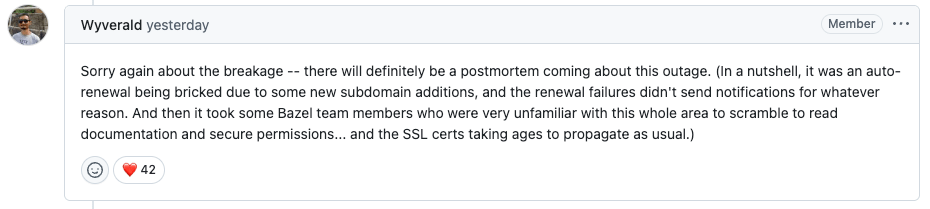

After mitigation, Xùdōng Yáng provided a brief summary of the incident on the Github ticket:

Say the words “expired SSL certificate” to any senior software engineer and watch the expression on their face. Everybody in this industry has been bitten by expired certs, including people who work at orgs that use automated certificate renewal. In fact, this very case is an example of an automated certificate renewal system that failed! From the screenshot above:

it was an auto-renewal being bricked due to some new subdomain additions, and the renewal failures didn’t send notifications for whatever reason.

The reality is that SSL certificates are a fundamentally dangerous technology, and the Bazel case is a great example of why. With SSL certificates, you usually don’t have the opportunity to build up operational experience working with them, unless something goes wrong. And things don’t go wrong that often with certificates, especially if you’re using automated cert renewal! That means when something does go wrong, you’re effectively starting from scratch to figure out how to fix it, which is not a good place to be. Once again, from that summary:

And then it took some Bazel team members who were very unfamiliar with this whole area to scramble to read documentation and secure permissions…

Now, I don’t know the specifics of the Bazel team composition: it may very well be that they have local SSL certificate expertise on the team, but those members were out-of-office because of the holiday. But even if that’s the case, with an automated set-it-and-forget-it solution, the knowledge isn’t going to spread across the team, because why would it? It just works on its own.

That is, until it stops working. And that’s the other dangerous thing about SSL certificates: the failure mode is the opposite of graceful degradation. It’s not like there’s an increasing percentage of requests that fail as you get closer to the deadline. Instead, in one minute, everything’s working just fine, and in the next minute, every http request fails. There’s no natural signal back to the operators that the SSL certificate is getting close to expiry. To make things worse, there’s no staging of the change that triggers the expiration, because the change is time, and time marches on for everyone. You can’t set the SSL certificate expiration so it kicks in at different times for different cohorts of users.

In other words, SSL certs are a technology with an expected failure mode (expiration) that absolutely maximizes blast radius (a hard failure for 100% of users), without any natural feedback to operators that the system is at imminent risk of critical failure. And with automated cert renewal, you are increasing the likelihood that the responders will not have experience with renewing certificates.

Is it any wonder that these keep biting us?

Our SSL issuer sends emails, but it depends on the recipients paying attention. Thirty days out they start, but typically they sit on them until a week ahead. This creates complacency of people ignoring the notification, which is dangerous.

We also have weird flows. The recipients have to send a request to another team who initiate yhe renewal. Another approves it. Then where the certificate gets updated is all over the place. Some are to appliances. Some are on servers. Some get sent to vendors. It’s wild.

I’d push back some on the characterization of SSL certs as “dangerous”. Yes, there are dangers to them, but there are also dangers to operating without them. Just like, if you have locks on your doors, it means there’s a danger you won’t be able to get back into your house if you lose your keys. I don’t think that makes the locks themselves “dangerous”.

There’s plenty that could be done to minimize the dangers of expired certificates, too. If the Bazel registry is so mission-critical, it could use a round-robin of multiple servers, each with a different hostname and a different SSL certificate. That way, if any one host fails (for any reason, not just SSL certificate expiry) users will still be able to access one of the others. The fact that bcr.bazel.build resolves to only a single IP address, and that Bazel exclusively depends uses that hostname for all registry operations, seems like a dangerous single point of failure in plenty of ways that can’t be blamed on SSL, too.

Putting that aside, SSL certificates are a security feature. They can’t be completely maintenance-free or they stop being effective. Automatic renewal has made the process a lot more seamless most of the time. (Though, there are tradeoffs — in addition to the lack of familiarity among operations staff, as you mentioned, auto-renewed certs typically have short, three-month lifetimes. Bazel got bitten by that, as well.) But when a certificate expires, refusing the request means that the only danger is some lost productivity. That’s a lot better than alternatives (like falling back to an insecure request) which could leave users open to much greater dangers like man-in-the-middle attacks or malware injection via spoofed package payloads.

When all’s said and done, I’ll suffer through some downtime due to an occasional outage, if the alternative is having to worry that everything I download may have been tampered with.

SSL certificates are not necessary — validated key presentation is necessary. That doesn’t require a certificate issued by a third party.

I’ve never been bitten by an expired TLS certificate, because I avoid this racket, so the expression seen on my face would be eye rolling dismissal. I’ve no clue what Bazel is, but I’m replying primarily in response to FeRDNYC here.

> Just like, if you have locks on your doors, it means there’s a danger you won’t be able to get back into your house if you lose your keys. I don’t think that makes the locks themselves “dangerous”.

Of course not, but notice that only people with landlords have to ask for permission to install locks, and only people with landlords must worry seriously about their landlord using a skeleton key to open them without permission. The TLS certificate is a key component of a cartel behaviour: The Internet can’t be centralized, although they’re certainly trying with the WWW, but merely controlling the disgustingly-complicated WWW browsers is enough to get centralized behaviour. It’s a simple playbook: Google works really hard to make certain that as few WWW browsers as feasible exist, ideally only Google’s, and then starts mandating new TLS requirements. Now most of the WWW exists at the behest of a handful of untrustworthy “certificate authorities” who will as a group deny certificates to certain websites as soon as they think they’ll get away with it.

> That’s a lot better than alternatives (like falling back to an insecure request) which could leave users open to much greater dangers like man-in-the-middle attacks or malware injection via spoofed package payloads.

I think it’s pretty clear that the malware always comes with all of the correct bells and whistles these days.

> When all’s said and done, I’ll suffer through some downtime due to an occasional outage, if the alternative is having to worry that everything I download may have been tampered with.

Oh, we’ll suffer much more than that, don’t worry.

Since at least 2015 with the deprecation of SSL 3.0 the technology is named TLS.

So people that still call it SSL are not up to date anymore.

There are documented ways on how to check how many days a certificate will still be valid for every monitoring solution out there (Prometheus, Icinga, Nagios etc.) so there is no reason to be surprised at all.

Your “response” to FeRDNYC is comprised of a paranoid conspiracy theory and a general, unhelpful statement about security breaches.

In fact, FeRDNYC’ post is a logical and cogent viewpoint that I whole heartedly agree with.

As FeRDNYC correctly pointed out, the problem with this article is that its title does not match the issue described in the article itself; SSL certs are not in and of themselves “dangerous”. Rather, the use of certain strategies in maintaining them are.

Your article is interesting, but I don’t agree that SSL certs are the problem. The ‘problem’ here is automation, which you do touch on.

The problem is that as we get more and more automation and things get ever more complicated within our hyper-virtualised environments there are fewer and fewer people that fully understand them and as these engineers build automation, the techs that follow behind them only learn the automation and do not fully understand how things work under the covers!!

@Martin: perhaps you are unaware, but the use of “SSL” is a colloquialism. Everyone even tangentially involved with certificate management understands that TLS superceded SSL a long time ago; it’s just easier and more familiar to others to call them SSL certs; it’s not that we are not up-to-date.

Very few organisations manage PKI well let alone what certs they have within their network and devices.

A laptop typically has a couple of hundred thousand certs and although some will be multi purpose, many are unknown. It is why we have discovered CNNIC certs in a Trident Submarine partner and 999 years full admin access certs in Accenture’s gold standard laptops.

I spoke with two high tech IT staff recently from the same firm and asked them if they were aware that their SSL cert was about to expire. Both said everything is automated. I knew the SSL cert was going to expire a it did. The issue is that automation encourages a hands off approach. Everyone assumes automation always works but they miss out on the verification layer. If I may plug my app ChillSSL.com which I built to help.

Which is why you should impending expirations using tools like Zabbix or CheckMK. Simple set warn/crit levels on something like 10/5 days (which is when renewals should have been in place anyway) so there’s plenty of time to do a manual renewal. SSL certificates aren’t inherently risky, lack of monitoring is.