Cloudflare just posted a public write-up of an incident that they experienced on Feb. 20, 2026. While it was large enough for them to write it up like this, it looks like the impact is smaller than the previous Cloudflare incidents I’ve written about here. Given that Cloudflare continues to produce the most detailed public incident write-ups in the industry, I still find them insightful. After all, the insight you get from an incident write-up is not related to the size of the impact! Here are some quick observations from this one.

System intended to improve reliability contributed to incident

The specific piece of configuration that broke was a modification attempting to automate the customer action of removing prefixes from Cloudflare’s BYOIP service, a regular customer request that is done manually today. Removing this manual process was part of our Code Orange: Fail Small work to push all changes toward safe, automated, health-mediated deployment.

Cloudflare has been doing work to improve reliability. In this case, they were working to automate a potentially dangerous manual operation to reduce the risk of making changes. Unfortunately, they got bitten by a previously undiscovered bug in the automation.

How do you pass the flag?

When I first read this write-up, I thought the issue was that they had done a query which was supposed to have a scope, but it was missing a scope, and so returned everything. But that’s not actually what happened.

(I’ve seen the accidentally unscoped query failure mode multiple times in my career, but that’s not actually what happened here)

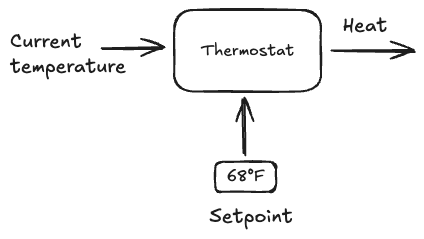

Instead, what happened here was that the client meant to set the pending_delete flag when making a query against an API.

Based on my reading, the server expected something like this:

GET /v1/prefixes?pending_delete=trueInstead, the client did this:

GET /v1/prefixes?pending_deleteThe server code looked like:

if v := req.URL.Query().Get("pending_delete"); v != "" { // server saw v=="", so this block wasn't executed ... return;}// this was executed isntead!It sounds like there was a misunderstanding about how to pass the flag, based on this language in the write-up:

One of the issues in this incident is that the pending_delete flag was interpreted as a string, making it difficult for both client and server to rationalize the value of the flag.

This is a vicious logic bug, because what happened was that instead of returning the entries to be deleted, the server returned all of them.

Cleanup, but still in use

Since the list of related objects of BYOIP prefixes can be large, this was implemented as part of a regularly running sub-task that checks for BYOIP prefixes that should be removed, and then removes them. Unfortunately, this regular cleanup sub-task queried the API with a bug.

This particular failure involved an automated cleanup task, to replace the manual work that a Cloudflare operator previously had to perform to do the dangerous step of removing published IP prefixes. In this case, due to a logic error, active prefixes were deleted.

Here, there was a business requirement to do the cleanup, it was to fulfill a request of a customer to remove prefix. More generally, cleanup itself is always an inherently dangerous process. It’s one of the reasons that code bases can end up such crufty places over time: we might be pretty sure that a particular bit of code, config, or data, is no longer in use. But are we 100% sure? Sure enough to take the risk of deleting it? The incentives generally push people towards a Chesterton’s Fence-y approach of “eh, safer to just leave it there”. The problem is that not cleaning up is also risky.

Reliability work in-flight

As a part of Code Orange: Fail Small, we are building a system where operational state snapshots can be safely rolled out through health-mediated deployments. In the event something does roll out that causes unexpected behavior, it can be very quickly rolled back to a known-good state. However, that system is not in Production today.

Recovery took longer than they would have liked here: full resolution of all of the IP prefixes took about six hours. Cloudflare already had work in progress to remediate problems like this more quickly! But it wasn’t ready yet. Argh!

Alas, this is unavoidable. Even when we are explicitly aware of risks, and we are working actively to address those risks, the work always takes time, and there’s nothing we can do but accept the fact that the risk will be present until our solution is ready.

People adapt to bring the system back to healthy

Affected BYOIP prefixes were not all impacted in the same way, necessitating more intensive data recovery steps… a global configuration update had to be initiated to reapply the service bindings for [a subset of customers that also had service bindings removed] to every single machine on Cloudflare’s edge.

The failure modes were different for different customers. In some cases, customers were able to take action themselves to remediate the issue through the Cloudflare dashboard. There were also more complex cases where Cloudflare engineers had to take action to restore service.

The write-up focuses primarily on the details of the failure mode. It sounds like the engineers had to do some significant work in the moment (intensive data recovery steps) to recover the tougher cases. This is where resilience really comes into play. The write-up hints at the nature of this work (reapply service bindings… to every single machine on Cloudflare’s edge). Was there pre-existing tooling to do this? Or did they have to improvise a solution? This is the most interesting part to me, and I’d love to know more about this work.