I was listening to Todd Conklin’s Pre-Accident Investigation Podcast the other day, to the episode titled When Normal Variability Breaks: The ReDonda Story. The name ReDonda in the title refers to ReDonda Vaught, an American registered nurse. In 2017, she was working at the Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville when she unintentionally administered the wrong drug to a patient under her care, a patient who later died. Vaught was fired, then convicted by the state of Tennessee for criminally negligent homicide and abuse of an impaired adult. It’s a terrifying story, really a modern tale of witch-burning, but it’s not what this post is about. Instead, I want to home in a term from the podcast title: normal variability.

In the context of the field of safety, the term variability refers to how human performance is, well, variable. We don’t always do the work the exact same way. This variation happens between humans, where different people will do work in different ways. And the variation also happens within humans, the same person will perform a task differently over time. The sources of variation in human performance are themselves varied: level of experience, external pressures being faced by the person, number of hours of sleep the night before, and so on.

In the old view of safety, there is an explicitly safe way to perform the work, as specified in documented procedures. Follow the procedures, and incidents won’t happen. In the software world, these procedures might be: write unit tests for new code, have the change reviewed by a peer, run end-to-end tests in staging, and so on. Under this view of the world, variability is necessarily a bad thing. Since variability means people do work differently, and since safety requires doing work the proscribed way, human variability is a source of incidents. Traditional automation doesn’t have this variability problem: it always does the work the same way. Hence you get the old joke:

The factory of the future will have only two employees: a man and a dog. The man will be there to feed the dog. The dog will be there to keep the man from touching the equipment.

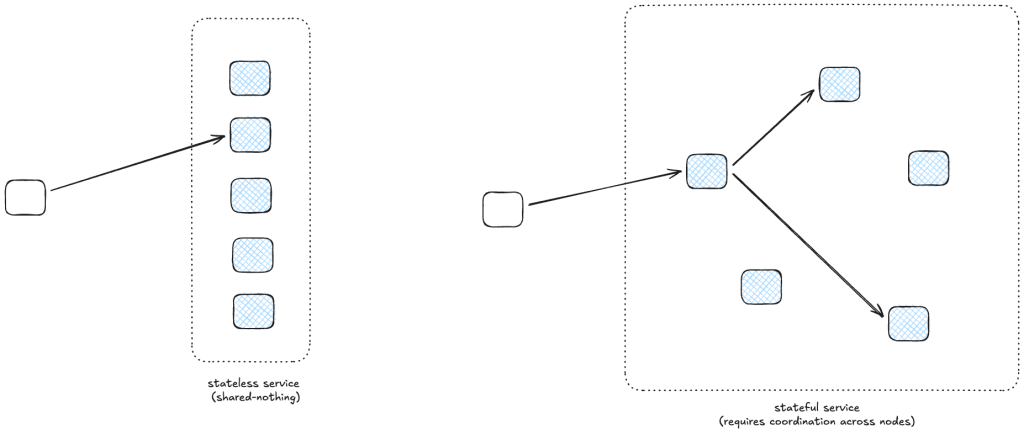

In the new view of safety, normal variability is viewed as an asset rather than a liability. In this view, the documented procedures for doing the work are always inadequate, they can never capture all of the messy details of real work. It is the human ability to adapt, to change the way that they do the work based on circumstances, that creates safety. That’s why you’ll hear resilience engineering folks use the (positive) term adaptive capacity rather than the (more neutral) human variability, to emphasize that human variability is, quite literally, adaptive. This is why tech companies still staff on-call rotations even though they have complex automation that is supposed to keep things up and running. It’s because the automation can never handle all of the cases that the universe will throw at it. Even sophisticated automation always eventually proves too rigid to be able to handle some particular circumstance that was never foreseen by the designers. This is the perfect-storm, weird-edge-case stuff that post-incident write-ups are made of.

This, again, brings us back to AI.

My own field of software development is being roiled by the adoption of AI-based coding tools like Anthropic’s Claude Code, OpenAI’s Codex, and Google’s Gemini Code Assist. These AI tools are rapidly changing the way that software is being developed, and you can read many blog posts of early adopters who are describing their experiences using these new tools. Just this week, there was a big drop in the market value of multiple software companies; I’ve already seen references to the beginning of the SaaS-Pocalypse, the idea being that companies will write bespoke tools using AI rather than purchasing software from vendors. The field of software development has seen a lot of change in terms of tooling in my own career, but one thing that is genuinely different about these AI-based tools is that they are inherently non-deterministic. You interact with these tools by prompting them, but the same prompt yields different results.

Non-determinism in software development tools is seen as a bad thing. The classic example of non-determinism-as-bad is flaky tests. A flaky test is non-deterministic: the same input may lead to a pass or a fail. Nobody wants non-determinism like this in our test suite. On the build side of things, we hope that our compiler emits the same instructions given the same source file and arguments. There’s even a whole movement around reproducible builds, the goal of which is to stamp out all of the non-determinism in the process of producing binaries from the original source code, where the ideal is achieving bit-for-bit identical binaries. Unsurprisingly, then, the non-determinism of the current breed of AI coding tools is seen as a problem. Here’s a quote from a recent article in the Wall Street Journal by Chip Cutter and Sebastian Herrera: Here’s Where AI Is Tearing Through Corporate America:

Satheesh Ravala is chief technology officer of Candescent, which makes digital technology used by banks and credit unions. He has fielded questions from employees about what innovations like Anthropic’s new features mean for the company, and responded by telling them banks rely on the company for software that does exactly what it’s supposed to every time—something AI struggles with.

“If I want to transfer $10,” he said, “it better be $10 not $9.99.”

I believe the AI coding tools are only going to improve with time, though I don’t feel confident in predicting whether future improvements will be orders-of-magnitude or merely incremental. What I do feel confident in predicting is that the non-determinism in these tools isn’t going away.

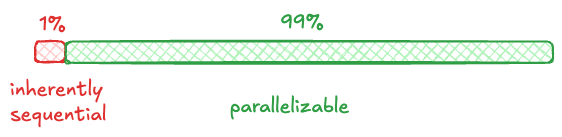

At their heart, these tools are sophisticated statistical models: they are prediction machines. When you’re chatting with one, it is predicting the next word to say, and then it feeds back the entire conversation so far, predicts the next word to say again, and so on. Because they are statistical models, there is some probability distribution of next word to predict. You could build the system to always choose the most likely word to say next. Statistical models aren’t just an AI thing, and many statistical models do use such a maximum likelihood approach. But that’s not what LLMs do in general. Instead, there’s some randomness that is intentionally injected into the system so that it doesn’t always just pick the most likely next word, but instead does a biased random selection of the next word, based on the statistical model of what’s most likely to come next, and based on a parameter called temperature, drawing an analogy to physics. If the temperature is zero, then the system always outputs the most likely next word. The higher the temperature, the more random the selection is.

What’s fascinating to me about this is the deliberate injection of randomness improved the output of the models, as judged qualitatively by humans. In other words, increasing the variability of the system improved outcomes.

Now, these LLMs haven’t achieved the level of adaptability that humans possess, though they can certainly perform some impressive cognitive tasks. I wouldn’t say they have adaptive capacity, and I firmly believe that humans will still need to be on-call for software system for the remainder of my career, despite the proliferation of AI SRE solutions. But what I am saying instead is that the ability of LLMs to perform cognitive tasks well depends upon them being able to leverage variability. And my prediction is that this dependence on variability isn’t going to go away. LLMs will get better, and they might even get much better, but I don’t think they’ll ever be deterministic. I think variability is an essential ingredient for a system to be able to perform these sorts of complex cognitive tasks.