If you’ve ever worked at a larger organization, stop me if you’ve heard (or asked!) any of these questions:

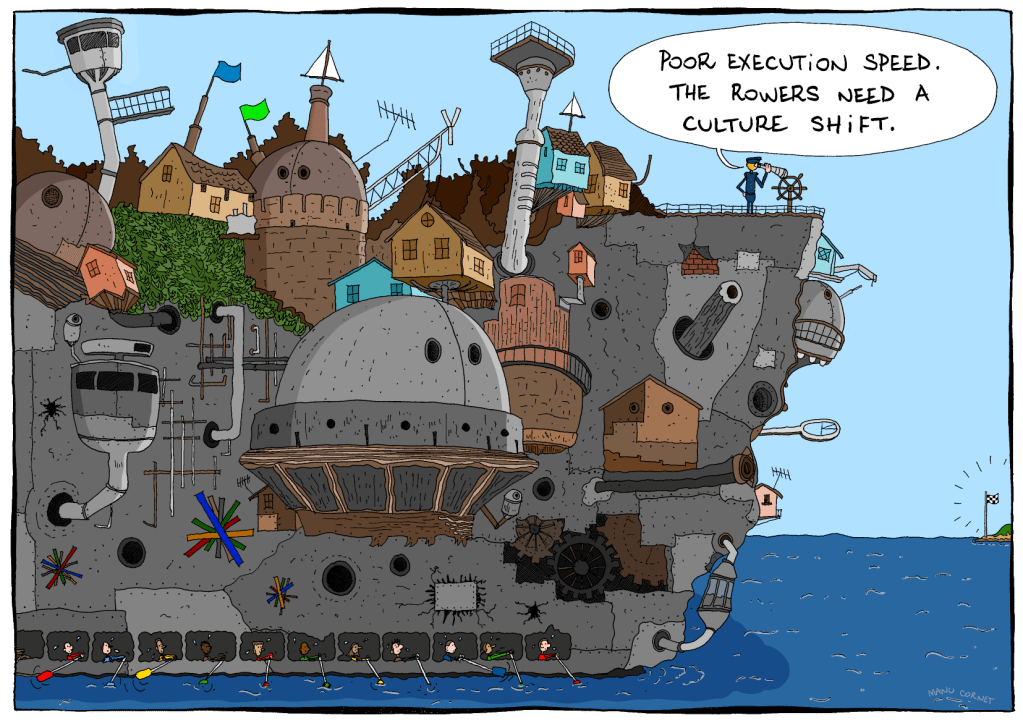

- “Why do we move so slowly as an organization? We need to figure out how to move more quickly.”

- “Why do we work in silos? We need to figure out how to break out of these.”

- “Why do we spend so much of our time in meetings? We need to explicitly set no-meeting days so we can actually get real work done.”

- “Why do we maintain multiple solutions for solving what’s basically the same problem? We should just standardize on one solution instead of duplicating work like this.”

- “Why do we have so many layers of management? We should remove layers and increase span of control.”

- “Why are we constantly re-org’ing? Re-orgs so disruptive.”

(As an aside, my favorite “multiple solutions” example is workflow management systems. I suspect that every senior-level engineer has contributed code to at least one home-grown workflow management system in their career).

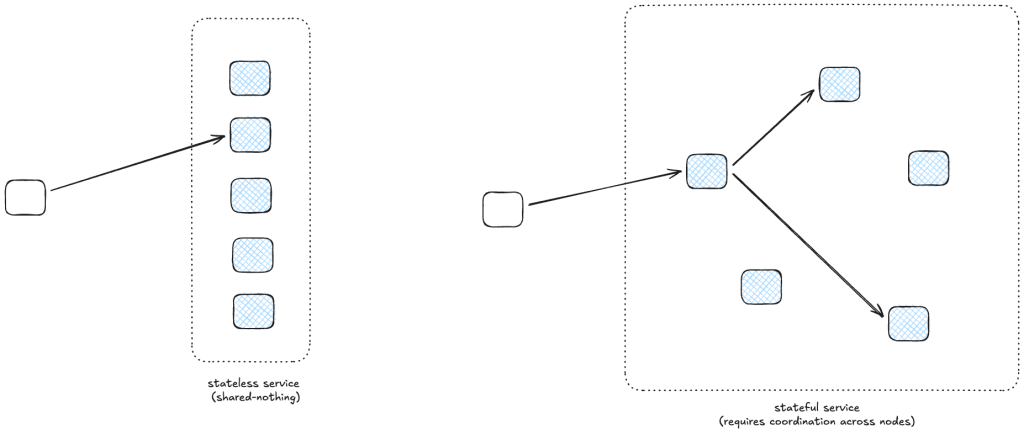

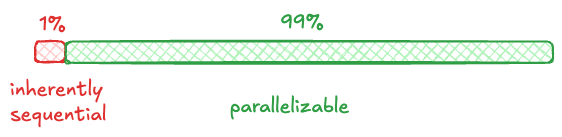

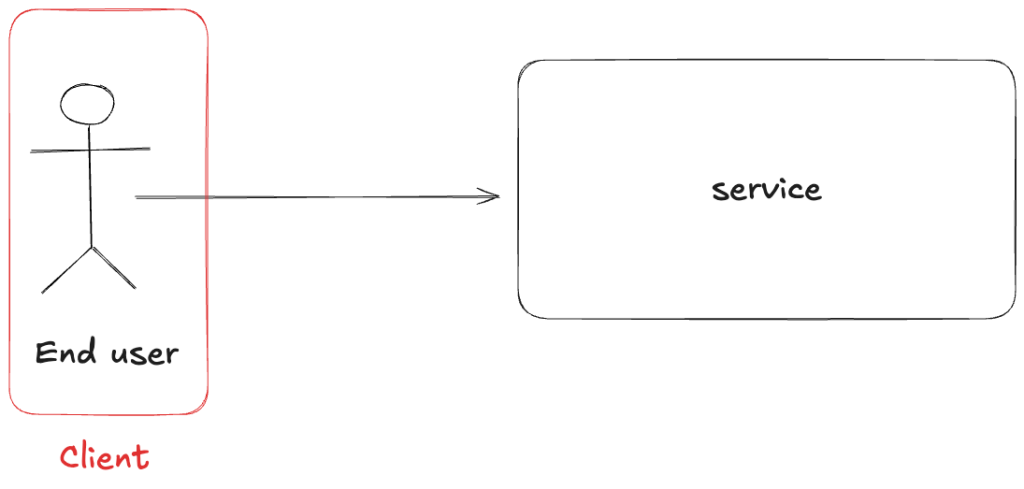

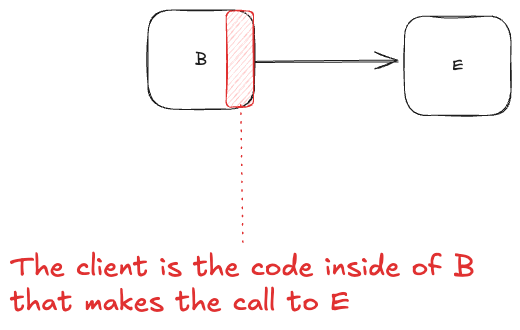

The answer to all of these questions is the same: because coordination is expensive. It requires significant effort for a group of people to work together to achieve a task that is too large for them to accomplish individually. And the more people that are involved, the higher that coordination effort grows. This is both “effort” in terms of difficulty (effortful as hard), and in terms of time (engineering effort, as measured in person-hours). This is why you see siloed work and multiple systems that seem to do the same thing. It’s because it requires less effort to work within your organization then to coordinate across organization, the incentive is to do localized work whenever possible, in order to reduce those costs.

Time spent in meetings is one aspect of this cost, which is something people acutely feel, because it deprives them of their individual work time. But the meeting time is still work, it’s just unsatisfying-feeling coordination work. When was the last time you talked about your participation in meetings in your annual performance review? Nobody gets promoted for attending meetings, but we humans need them to coordinate our work, and that’s why they keep happening. As organizations grow, they require more coordination, which means more resources being put into coordination mechanisms, like meetings and middle management. It’s like an organizational law of thermodynamics. It’s why you’ll hear ICs at larger organizations talk about Tanya Reilly’s notion of glue work so much. You’ll hear companies run “One <COMPANY NAME>” campaigns at larger companies as an attempt to improve coordination; I remember the One SendGrid campaign back when I worked there.

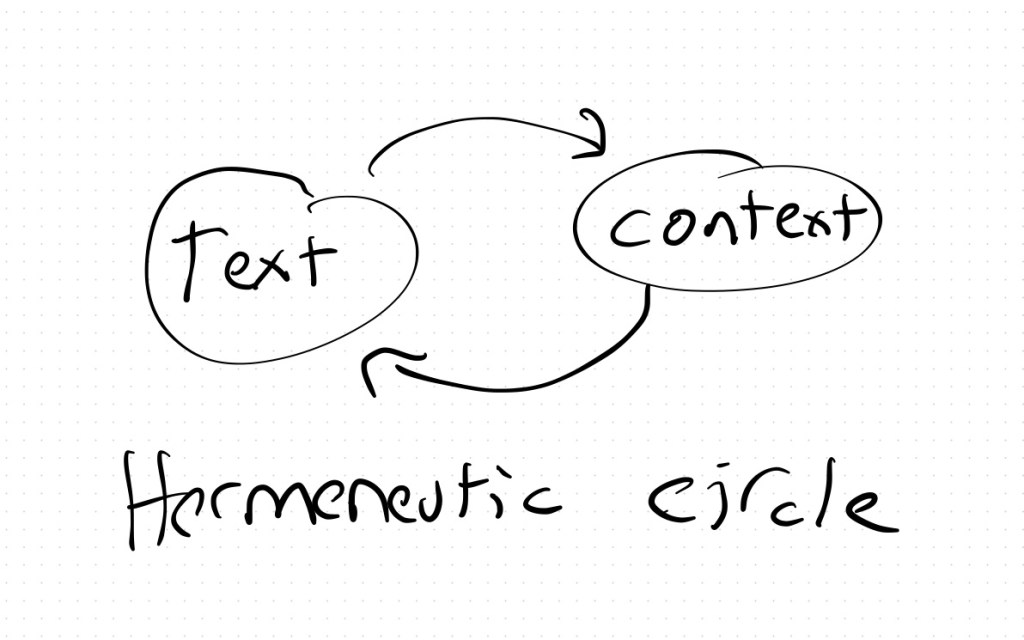

Because of the challenges of coordination, there’s a brisk market in coordination tools. Some examples off the top of my head include: Gantt charts, written specifications, Jira, Slack, daily stand-ups, OKRs, kanban boards, Asana, Linear, pull requests, email, Google docs, Zoom, I’m sure you could name dozens more, including some that are no longer with us. (Remember Google Wave?). Heck, both spoken and written language are the ultimately communication ur-tools.

And yet, despite the existence of all of those tools, it’s still hard to coordinate. Remember back in 2002 when Google experimented with eliminating engineering managers? (“That experiment lasted only a few months“). And then in 2015 when Zappos experimented with holacracy? (“Flat on paper, hierarchy in practice.“) I don’t blame them for trying different approaches, but I’m also not surprised that these experiments failed. Human coordination is just fundamentally difficult. There’s no one weird trick that is going to make the problem go away.

I think it’s notable that large companies try different strategies to try to manage ongoing coordination costs. Amazon is famous for using a decentralization strategy, they have historically operated almost like a federation of independent startups, and enforce coordination through software service interfaces, as described in Steve Yegge’s famous internal Google memo. Google, on the other hand, is famous for using an invest-heavily-in-centralized-tooling approach to coordination. But there are other types of coordination that are outside of the scope of these sorts of solutions, such as working on an initiative that involves work from multiple different teams and orgs. I haven’t worked inside of either Amazon or Google, so I don’t know how well things work in practice there, but I bet employees have some great stories!

During incidents, coordination becomes an acute problem, and we humans are pretty good at dealing with acute problems. The organization will explicitly invest in an incident manager on-call rotation to help manage those communication costs. But coordination is also a chronic problem in organizations, and we’re just not as good at dealing with chronic problems. The first step, though, is recognizing the problem. Meetings are real work. That work is frequently done poorly, but that’s an argument for getting better at it. Because that’s important work that needs to get done. Oh, also, those people doing glue work have real value.