On September 18, 2025, the Australian telecom company Optus experienced an incident where many users were unable to make emergency service calls from their cell phones. For almost 14 hours, about 75% of calls made to 000 (the Australian version of 911) failed to go through, when from South Australia, Western Australia, the Northern Territory, and parts of New South Wales.

The Optus Board of Directors commissioned an independent review of the incident, led by Dr. Kerry Schott. On Thursday, Optus released Dr. Schott’s report, which the press release refers to as the Schott Review. This post contains my quick thoughts on the report.

As always, I recommend that you read the report yourself first before reading this post. Note that all quotes are from the Schott Review unless indicated otherwise.

The failure mode: a brief summary

I’ll briefly recap my understanding of the failure mode, based on my reading of the report. (I’m not a network engineer, so there’s a good chance I’ll get some details wrong here).

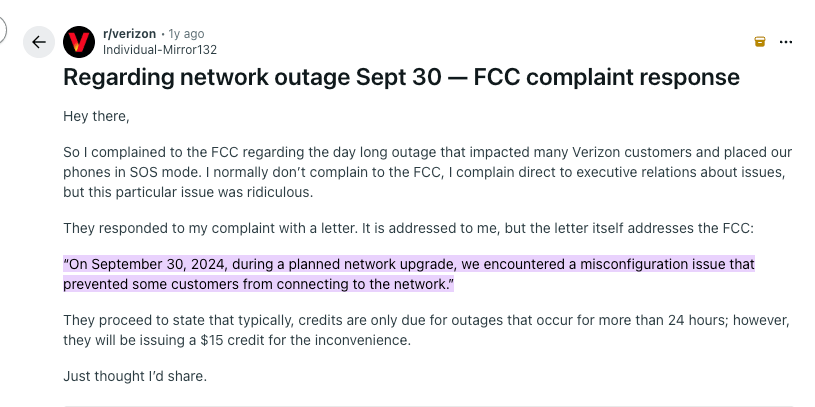

Optus contracts with Nokia to do network operations work, and the problem occurred while Nokia network engineers were carrying out a planned software upgrade of multiple firewalls at the request of Optus.

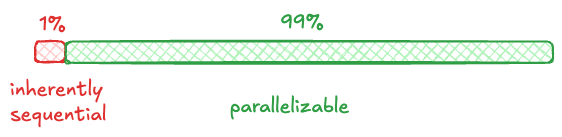

There were eighteen firewalls that required upgrading. The first fifteen upgrades were successful: the problem occurred when upgrading the sixteenth firewall. Before performing the upgrade, the network engineer isolated the firewall so that it would not serve traffic while it was being upgraded. However, the traffic that would normally pass through this firewall was not rerouted to another active firewall. The resulting failure mode only affected emergency calls: regular phone calls that would normally traverse the offline firewall were automatically rerouted, but the emergency calls were not. As a result, 000 calls were blocked for the customers whose calls would normally traverse this firewall.

Mistakes were made

These mistakes can only be explained by a lack of care about a critical service and a lack of disciplined adherence to procedure. Processes and controls were in place, but the correct process was not followed and actions to implement the controls were not done or not done properly. – Independent Report – The Triple Zero Outage at Optus: 18 September 2025

One positive thing I’ll say about the tech industry: everybody at least pays lip service to the idea of blameless incident reviews. The Schott Review, on the other hand, does not. The review identifies ten mistakes that engineers made:

- Some engineers failed to attend project meetings to assess impact of planned work.

- The pre-work plan did not clearly include a traffic rerouting before the firewall was isolated.

- Nokia engineers chose the wrong method of procedure to implement the firewall upgrade change request (missing traffic rerouting).

- The three Nokia engineers who reviewed the chosen method of procedure did not notice the missing traffic rerouting step.

- The risk of the change was incorrectly classified as ‘no impact’, and the urgency of the firewall upgrade was incorrectly classified as ‘urgent’.

- The firewall was incorrectly classified as ‘low risk’ in the configuration management database (CMDB) asset inventory

- The upgrade was performed using the wrong method of procedure

- Both a Nokia and an Optus alert fired during the upgrade. Nokia engineers assumed the alert was a false alarm due to the upgrade. Optus engineers opened an incident and reached out to Nokia command centre to ask if it was related to the upgrade. No additional investigation was done.

- The network engineers who did the checks to ensure that the upgrade was successful did not notice that the call failure rates were increasing.

- Triple Zero call monitoring was aggregated at the national level, so it could not identify region-specific failures.

Man, if I ever end up teaching a course in incident investigations, I’m going to use this report as an example of what not to do. This is hindsight-bias-palooza, with language suffused with human error.

What’s painful to me reading this is the acute absence of curiosity about how it was that these mistakes came to happen. For example, mistakes 5 and 6 involve classifications. The explicit decision to make those classifications must have made sense to the person in the moment, otherwise they would not have made those decisions. And yet, the author conveys zero interest in that question at all.

In other cases, the mistakes are things that were not noticed. For example, mistake 4 involves three (!) reviewers not noticing an issue with a procedure, and mistake 9 involves not noticing that call failure rates were increasing. But it’s easy to point at a graph after the incident and say “this graph indicates a problem”. If you want to actually improve, you need to understand what conditions led to that not being noticed when the actual check happened. What about the way the work is done made it less likely that this would not be seen? For example, is there a UX issue in the standard dashboards that makes this hard to see? I don’t know the answer to that reading the report, and I suspect Dr. Schott doesn’t either.

What’s most damning, though, is the lack of investigation into what are labeled as mistakes 2 and 3:

The strange thing about this specific Change Request was that in all past six IX firewall upgrades in this program – one as recent as 4 September – the equipment was not isolated and no lock on any gateway was made.

For reasons that are unclear, Nokia selected a 2022 Method of Procedure which did not automatically include a traffic diversion before the gateway was locked.

How did this work actually get done? The report doesn’t say.

Now, you might say, “Hey, Lorin, you don’t know what constraints that Dr. Schott was working under. Maybe Dr. Schott couldn’t get access to the people who knew the answers to these questions?” And that would be an absolutely fair rejoinder: it would be inappropriate for me to pass judgment here without having any knowledge about how the investigation was actually done. But this is the same critique I’m leveling at this report: it passes judgment on the engineers who made decisions without actually looking at how real work normally gets done in this environment.

I also want to circle back to this line:

These mistakes can only be explained by a lack of care about a critical service and a lack of disciplined adherence to procedure. Processes and controls were in place, but the correct process was not followed and actions to implement the controls were not done or not done properly (emphasis mine).

None of the ten listed mistakes are about a process not being followed! In fact, the process was followed exactly as specified. This makes the thing labeled mistake 7 particularly egregious, because the mistake was the engineer corrrectly carrying out the selected and peer-reviewed process!

No acknowledgment of ambiguity of real work

The fact that alerts can be overlooked because they are related to ongoing equipment upgrade work is astounding, when the reason for those alerts may be unanticipated problems caused by that work.

The report calls out the Nokia and Optus engineers for not investigating the alerts that fired during the upgrade, describing this as astounding. Anybody who has done operational work can tell you that the signals that you receive are frequently ambiguous. Was this one such case? We can’t tell from the report.

In the words of the late Dr. Richard Cook:

11) Actions at the sharp end resolve all ambiguity.

Organizations are ambiguous, often intentionally, about the relationship between

production targets, efficient use of resources, economy and costs of operations, and

acceptable risks of low and high consequence accidents. All ambiguity is resolved by

actions of practitioners at the sharp end of the system. After an accident, practitioner actions may be regarded as ‘errors’ or ‘violations’ but these evaluations are heavily

biased by hindsight and ignore the other driving forces, especially production pressure.

— Richard Cook, How Complex Systems Fail

I personally find it astounding that somebody conducting an incident investigation would not delve deeper into how a decision that appears to be astounding would have made sense in the moment.

Some unrecognized ironies

There are several ironies in the report that I thought were worth calling out (emphasis mine in each case).

The firewall upgrade in this case was an IX firewall and no traffic diversion or isolation was required or performed, consistent with previous (successful) IX firewall upgrades.

Nevertheless, having expressed doubts about the procedure, it was decided by the network engineer to isolate the firewall to err on the side of caution. The problem with this decision was that the equipment was isolated, but traffic was not diverted.

Note how a judgment call intended to reduce risk actually increased it!

At the time of the incident, the only difference between the Optus network and other

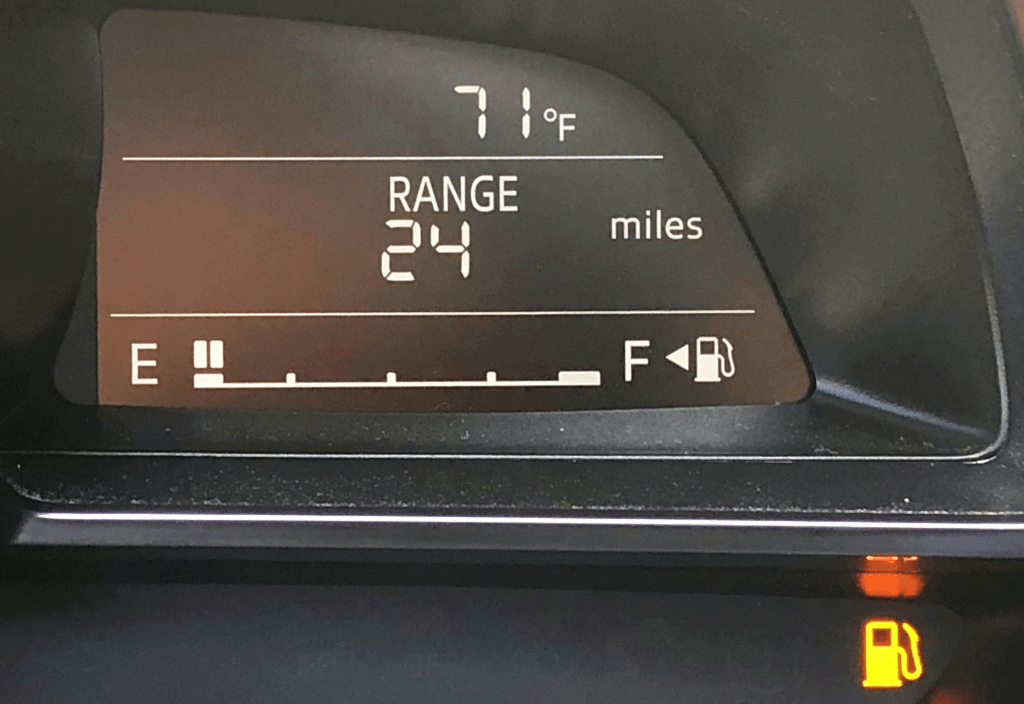

telecommunication networks was the different ‘emergency time-out’ setting. This setting (timer) controls how long an emergency call remains actively attempting to connect. The emergency inactivity timer at Optus was set at 10 seconds, down from the previous 600 seconds, following regulator concerns that Google Pixel 6A devices running Android 12 were unable to reconnect to Triple Zero after failed emergency calls. Google advised users to upgrade to Android 13, which resolved the issue, but Optus also reduced their emergency inactivity timer to 10 seconds to enable faster retries after call failures.

We understand that other carriers have longer time-out sets that may range from 150 to 600 seconds. It appears that the 10 second timing setting in the Optus network was the only significant difference between Optus’ network and other Australian networks for Triple Zero behaviour. Since this incident this time setting has now been changed by Optus to 600 seconds.

One of the contributors was a timeout, which had been previously reduced from 600 seconds to 10 seconds in order to address a previous problem failed emergency calls on specific devices.

Customers should be encouraged7 to test their own devices for Triple Zero calls and, if in doubt, raise the matter with Optus.

7 This advice is contrary to Section 31 of the ECS Determination to ‘take steps to minimise non-genuine calls’. It is noted, however, that all major carriers appear to be pursuing this course of action.

In one breath, the report attributes the incident to a lack of disciplined adherence to procedure. In another, the report explicitly recommends that customers test that 000 is working, noting in passing that this is advice contradicts Australian government policy.

Why a ‘human error’ perspective is dangerous

The reason a ‘human error’ perspective like this report is dangerous is because it hides away the systemic factors that led to those errors in the first place. By identifying the problem as engineers who failed to follow the procedure or were careless (what I call sloppy devs), we learn nothing about how real work in the system actually happens. And if you don’t understand how the real work happens, you won’t understand how the incident happens.

Two bright spots

Despite these criticisms, there are two sections that I wanted to call out as positive examples, as the kind of content I’d like to see more of in these sorts of documents.

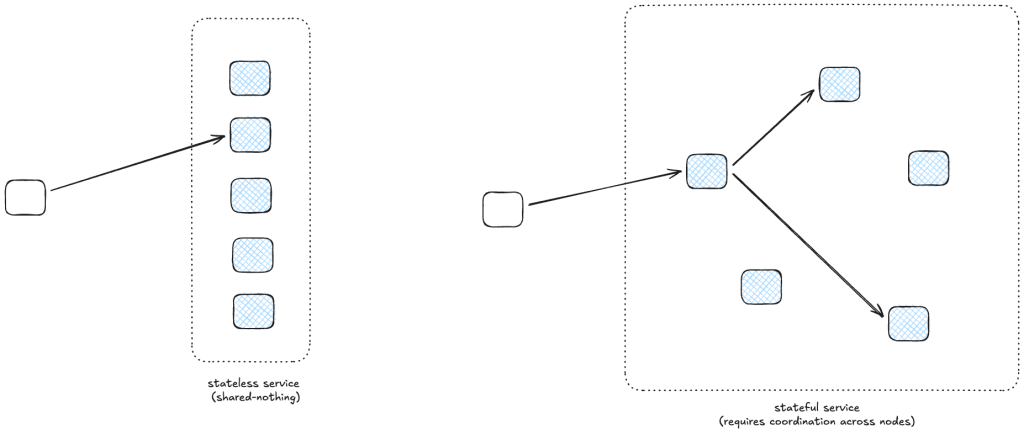

Section 4.3: Contract Management addresses a systemic issue, the relationship between Optus and a vendor of theirs, Nokia. This incident involved an interaction between the two organizations. Anyone who has been involved in an incident that involves a vendor can tell you that coordinating across organizations is always more difficult than coordinating within an organization. The report notes that Optus’s relationship with Nokia has historically been transactional, and suggests that Optus might consider whether it would see benefits moving to [a partnership] style of contract management for complex matters.

Section 5.1: A General Note on Incident Management discusses how it is more effective to have on hand a small team of trained staff who have the capacity to adapt to the circumstances as they unfold over having a large document that describes how to handle different types of emergency scenarios. If this observation gets internalized by Optus, then I think the report is actually net positive, despite my other criticisms.

What could have been

Another irony here is that Australia has a deep well of safety experts to draw from, thanks to the Griffith University Safety Science Innovation Lab. I wish a current or former associate of that lab had been contacted to do this investigation. Off the top of my head, I can name Sidney Dekker, David Provan, Drew Rae, Ben Hutchinson, and Georgina Poole. Any of them would have done a much better job.

In particular, The Schott Review is a great example of why Dekker’s The Field Guide to Understanding ‘Human Error’ remains such an important book. I presume the author of the report has never read it.

The Australian Communications and Media Authority (ACMA) is also performing an investigation into the Optus Triple Zero outage. I’m looking forward to seeing how their report compares to the Schott Review. Fingers crossed that they do a better job.