FizzBee is a new formal specification language, originally announced back in May of last year. FizzBee’s author, Jayaprabhakar (JP) Kadarkarai, reached out to me recently and asked me what I thought of it, so I decided to give it a go.

To play with FizzBee, I decided to model some algorithms that solve the mutual exclusion problem, more commonly known as locking. Mutual exclusion algorithms are a classic use case for formal modeling, but here’s some additional background motivation: a few years back, there was an online dust-up between Martin Kleppmann (author of the excellent book Designing Data-Intensive Applications, commonly referred to as DDIA) and Salvatore Sanfilippo (creator of Redis, and better known by his online handle antirez). They were arguing about the correctness of an algorithm called Redlock that claims to achieve fault-tolerant distributed locking. Here are some relevant links:

- Distributed Locks with Redis – description of the Redlock algorithm

- How to do distributed locking – Kleppmann’s critique of the Redlock algorithm

- Is Redlock safe? – antirez’s rebuttal to Kleppmann

As a FizzBee exercise, I wanted to see how difficult it was to model the problem that Kleppmann had identified in Redlock.

Keep in mind here that I’m just a newcomer to the language writing some very simple models as a learning exercise.

Critical sections

Here’s my first FizzBee model, it models the execution of two processes, with an invariant that states that at most one process can be in the critical section at a time. Note that this model doesn’t actually enforce mutual exclusion, so I was just looking to see that the assertion was violated.

# Invariant to check

always assertion MutualExclusion:

return not any([p1.in_cs and p2.in_cs for p1 in processes

for p2 in processes

if p1 != p2])

NUM_PROCESSES = 2

role Process:

action Init:

self.in_cs = False

action Next:

# before critical section

pass

# critical section

self.in_cs = True

pass

# after critical section

self.in_cs = False

pass

action Init:

processes = []

for i in range(NUM_PROCESSES):

processes.append(Process())

The “pass” statements are no-ops, I just use them as stand-ins for “code that would execute before/during/after the critical section”.

FizzBee is built on Starlark, which is a subset of Python, which why the model looks so Pythonic. Writing a FizzBee model felt like writing a PlusCal model, without the need for specifying labels explicitly, and also with a much more familiar syntax.

The lack of labels was both a blessing and a curse. In PlusCal, the control state is something you can explicitly reference in your model. This is useful for when you want to specify a critical section as an invariant. Because FizzBee doesn’t have labels, I had to create a separate variable called “in_cs” to be able to model when a process was in its critical section. In general, though, I find PlusCal’s label syntax annoying, and I’m happy that FizzBee doesn’t require it.

FizzBee has an online playground: you can copy the model above and paste it directly into the playground and click “Run”, and it will tell you that the invariant failed.

FAILED: Model checker failed. Invariant: MutualExclusion

The “Error Formatted” view shows how the two processes both landed on line 17, hence violating mutual exclusion:

Locks

Next up, I modeled locking in FizzBee. In general, I like to model a lock as a set, where taking the lock means adding the id of the process to the set, because if I need to, I can see:

- who holds the lock by the elements of the set

- if two processes somehow manage to take the same lock (multiple elements in the set)

Here’s my FizzBee mdoel:

always assertion MutualExclusion:

return not any([p1.in_cs and p2.in_cs for p1 in processes

for p2 in processes

if p1 != p2])

NUM_PROCESSES = 2

role Process:

action Init:

self.in_cs = False

action Next:

# before critical section

pass

# acquire lock

atomic:

require not lock

lock.add(self.__id__)

#

# critical section

#

self.in_cs = True

pass

self.in_cs = False

# release lock

lock.clear()

# after critical section

pass

action Init:

processes = []

lock = set()

in_cs = set()

for i in range(NUM_PROCESSES):

processes.append(Process())

By default, each statement in FizzBee is treated atomically, and you can specify an atomic block to treat multiple statements automatically.

If you run this in the playground, you’ll see that the invariant holds, but there’s a different problem: deadlock

DEADLOCK detected

FAILED: Model checker failed

FizzBee’s model checker does two things by default:

- Checks for deadlock

- Assumes that a thread can crash after any arbitrary statement

In the “Error Formatted” view, you can see what happened. The first process took the lock and then crashed. This leads to deadlock, because the lock never gets released.

Leases

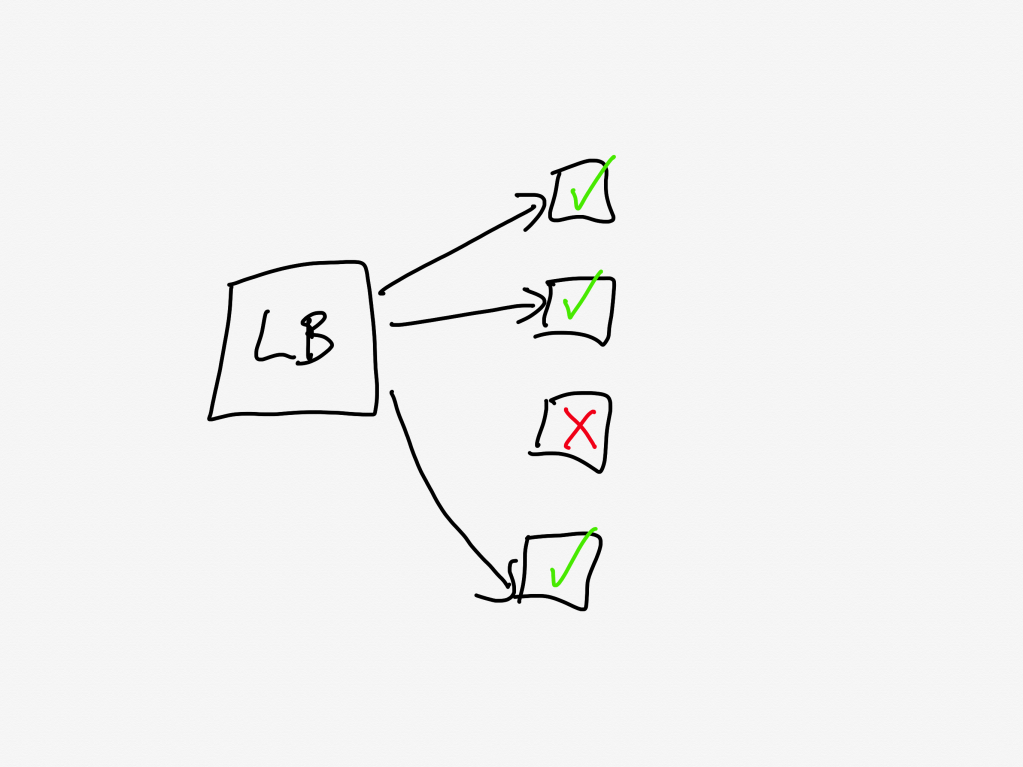

If we want to build a fault-tolerant locking solution, we need to handle the scenario where a process fails while it owns the lock. The Redlock algorithm uses the concept of a lease, which is a lock that expires after a period of time.

To model leases, we now need to model time. To keep things simple, my model assumes a global clock that all processes have access to.

NUM_PROCESSES = 2

LEASE_LENGTH = 10

always assertion MutualExclusion:

return not any([p1.in_cs and p2.in_cs for p1 in processes

for p2 in processes

if p1 != p2])

action AdvanceClock:

clock += 1

role Process:

action Init:

self.in_cs = False

action Next:

atomic:

require lock.owner == None or \

clock >= lock.expiration_time

lock = record(owner=self.__id__,

expiration_time=clock+LEASE_LENGTH)

# check that we still have the lock

if lock.owner == self.__id__:

# critical section

self.in_cs = True

pass

self.in_cs = False

# release the lock

if lock.owner == self.__id__:

lock.owner = None

action Init:

processes = []

# global clock

clock = 0

lock = record(owner=None, expiration_time=-1)

for i in range(NUM_PROCESSES):

processes.append(Process())

Now the lock has an expiration date, so we don’t have the deadlock problem anymore. But the invariant is no longer always true.

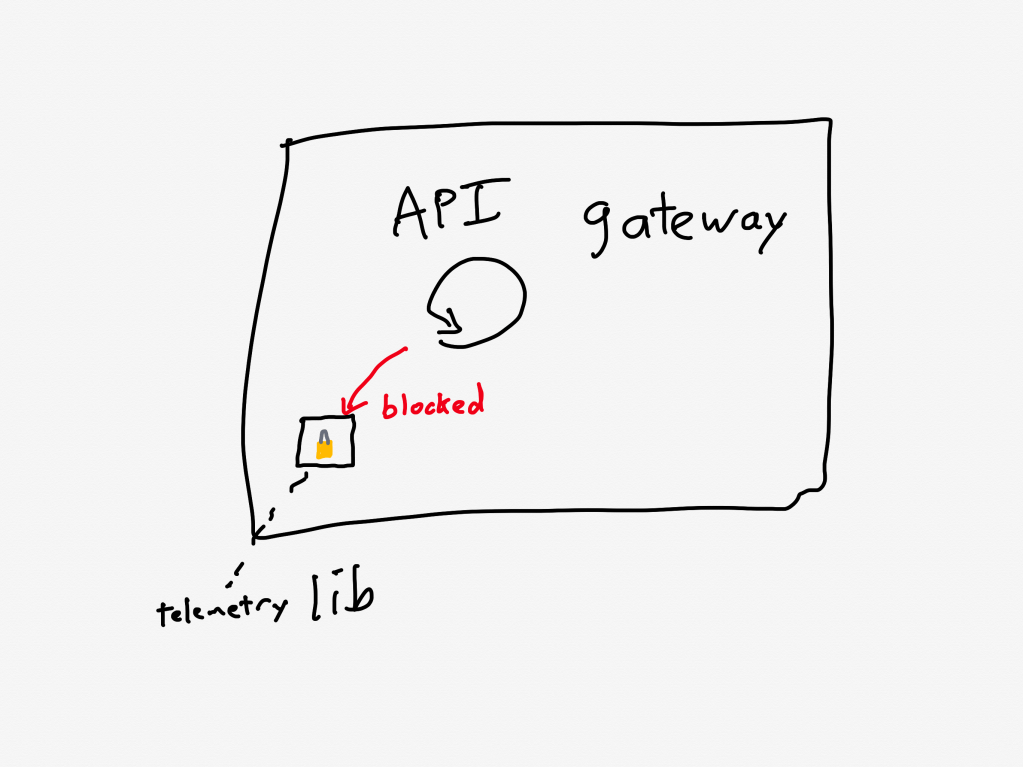

FizzBee also has a neat view called the “Explorer” where you can step through and see how the state variables change over time. Here’s a screenshot, which shows the problem:

The problem is that one process can think it holds the lock, but it the lock has actually expired, which means another process can take the lock, and they can both end up in the critical section.

Fencing tokens

Kleppmann noted this problem with Redlock, that it was vulnerable to issues where a process’s execution could pause for some period of time (e.g., due to garbage collection). Kleppmann proposed using fencing tokens to prevent a process from accessing a shared resource with an expired lock.

Here’s how I modeled fencing tokens:

NUM_PROCESSES = 2

LEASE_LENGTH = 10

always assertion MutualExclusion:

return not any([p1.in_cs and p2.in_cs for p1 in processes

for p2 in processes

if p1 != p2])

atomic action AdvanceClock:

clock += 1

role Process:

action Init:

self.in_cs = False

action Next:

atomic:

require lock.owner == None or \

clock >= lock.expiration_time

lock = record(owner=self.__id__,

expiration_time=clock+LEASE_LENGTH)

self.token = next_token

next_token += 1

# can only enter the critical section

# if we have the highest token seen so far

atomic:

if self.token > last_token_seen:

last_token_seen = self.token

# critical section

self.in_cs = True

pass

# after critical section

self.in_cs = False

# release the lock

atomic:

if lock.owner == self.__id__:

lock.owner = None

action Init:

processes = []

# global clock

clock = 0

next_token = 1

last_token_seen = 0

lock = record(owner=None, expiration_time=-1)

for i in range(NUM_PROCESSES):

processes.append(Process())

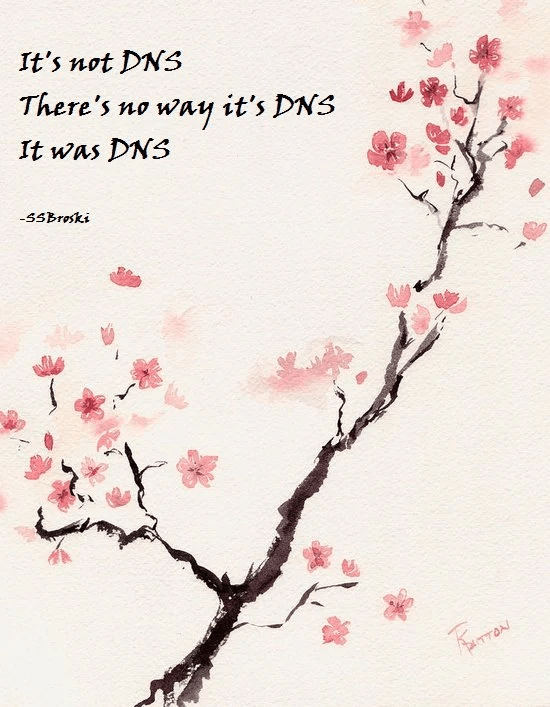

However, if you run this through the model checker, you’ll discover that the invariant is also violated!

It turns out that fencing tokens don’t protect against the scenario where two processes both believe they hold the lock, and the lower token reaches the shared resource before the higher token:

I reached out to Martin Kleppmann to ask about this, and he agreed that fencing tokens would not protect against this scenario.

Impressions

I found FizzBee surprisingly easy to get started with, although I only really scratched the surface here. In my case, having experience with PlusCal helped a lot, as I already knew how to write my specifications in a similar style. You can write your specs in TLA+ style, as a collection of atomic actions rather than as one big non-atomic action, but the PlusCal-style felt more natural for these particular problems I was modeling.

The Pythonic syntax will be much more familiar to programmers than PlusCal and TLA+, which should help with adoption. In some cases, though I found myself missing the conciseness of the set notation that languages like TLA+ and Alloy support. I ended up leveraging Python’s list comprehensions, which have a set-builder-notation feel to them.

Newcomers to formal specification will still have to learn how to think in terms of TLA+ style models: while FizzBee looks like Python, conceptually it is like TLA+, a notation for specifying a set of state-machine behaviors, which is very different from a Python program. I don’t know what it will be like for learners.

I was a little bit confused by FizzBee’s default behavior of a thread being able to crash at any arbitrary point, but that’s configurable, and I was able to use it to good effect to show deadlock in the lock model above.

Finally, while I read Kleppmann’s article years ago, I never noticed the issue with fencing tokens until I actually tried to model it explicitly. This is a good reminder of the value of formally specifying an algorithm. I fooled myself into thinking I understood it, but I actually hadn’t. It wasn’t until I went through the exercise of modeling it that I discovered something about its behavior that I hadn’t realized before.